Shrinking container images (part 1) - the Where and Why of big containers

Working with teams along their container adoption journey, I have a lot of conversations about “container size insecurity” from engineers comparing their new infrastructure to … anything, really. The most common questions I get are:

- You have such a small base image, but my finished workload isn’t much smaller than before! Why?

- Smaller images are inherently more secure, right?

- Is this container too big?

- How do I make this container smaller?

There’s a lot of ambiguity around what goes into the unambiguous numbers that define size (MB) or security (count of findings). Spending valuable time to make a container smaller may not impact security or depending on what’s attempted, could even break our application. Sadly, there’s also a lot of misinformation too.

Let’s unpack the relationship between size, security, and the practices that can help using some projects I maintain1, with a few examples to look at how each tactic impacts both container size and security.

Where we’re going 🗺️

Big containers in the wild

Containers don’t always give us svelte, secure microservices. Instead, “whole virtual machines in a container” is a pattern I see often in the field. These are typically “big” (often measured in gigabytes) and may have many security findings (usually measured in CVEs). Here’s some use cases where multipurpose containers are common:

- Continuous integration images (builders) for Jenkins, GitLab, GitHub Actions, etc.

- Complex or multi-language applications (frequently seen during “break the monolith up” transitions)

- Glob-of-tools-for-one-purpose image (common for static or dependency analysis, linting, regression testing, and more)

- Devcontainers - use a container to version-control your development environment and all dependencies

- Big java apps (Giant java enterprise applications have been my past few months’ of conversations, not trying to pick on it as a language or anything)

First, do less

Having a container image that does less by design is the simplest path to a smaller container. Usually this entails breaking each task into small services … yada yada yada … microservices are still cool. It may not be a feasible option, right here and right now (or ever) for the problem that needs solving. Rearchitecting software is expensive and time-consuming. It also doesn’t work equally well for every task, language, or framework.

Finding easy wins first

🤷🏻♀️ Software is hard. Refactoring is harder. Here’s some “quick wins” that tend to be easy to find and implement:

Find the biggest containers by sorting your internal container registry by size. If that’s not easy to get through the registry directly, a few commands will see what’s running in any given cluster. Here’s a one-liner to get you started:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

# list container image sizes in MB running in Kubernetes cluster

kubectl get pods --all-namespaces -o jsonpath="{range .items[*]}{.spec.containers[*].image}{'\n'}{end}" |\

while read -r image; do \

docker inspect --format='{{.RepoTags}} {{.Size}}' "$image" 2>/dev/null |\

awk '{print $1 ", " $2/1024/1024 " MB"}'; \

done |\

uniq |\

sort -k2 -nr

This’ll print a list that looks (more or less) like this:

1

2

3

4

5

[ghcr.io/some-natalie/kubernoodles/ubi9:latest], 877.548 MB

[ghcr.io/actions/gha-runner-scale-set-controller:0.10.1], 183.832 MB

[cgr.dev/some-natalie.dev/kyverno:latest], 153.512 MB

[cgr.dev/some-natalie.dev/kyverno-reports-controller:latest], 152.046 MB

... and so on ...

Now that we know what’s big, start looking into why it’s so big. Things I’ve found include:

- A data science team that copied entire data sets into their container. They didn’t know that using a volume mount or connecting to a shared storage service would be faster to run and straightforward to implement. This resulted in dozens of gigabytes of data in each container and many many terabytes of wasted space in backups by the time it was caught. 😱

- An operations team that had multiple versions of Java installed in the same container, because they weren’t sure which one the developers needed or when that would change. Simple communication could have fixed this one. 🙊

- A “golden images” team that used to build VMs ported their Packer build scripts into a Dockerfile. There were many inefficiencies in the build process because these tools work differently. There was also an opportunity to factor this system better - using multiple smaller options for the same set of tasks. This “golden container” was 15 GB in size. 😯

In all of these cases, a little education and even less effort to implement yielded tremendous reductions in size. Some of these also improved the security posture, reduced wasted resources, and made the developer experience faster.

Breaking up the monolith

I’m not getting into the microservice vs monolith debate. Once the decision’s been made to move, that transition state between the two can get complicated. It doesn’t always go according to the migration plan. So long as progress is being made and the users are happy, I’m not inclined to call this a problem.

The one “easy win” I have found here is less about the monolith itself and more about having multiple other services in a single image. For example, a container would have both its’ internal logic for a task as well as a cache or queue system. The same is true of web servers or file storage systems. Breaking these out into a separate service is sometimes one of the simpler tasks to accomplish “doing less”.

Continuous integration

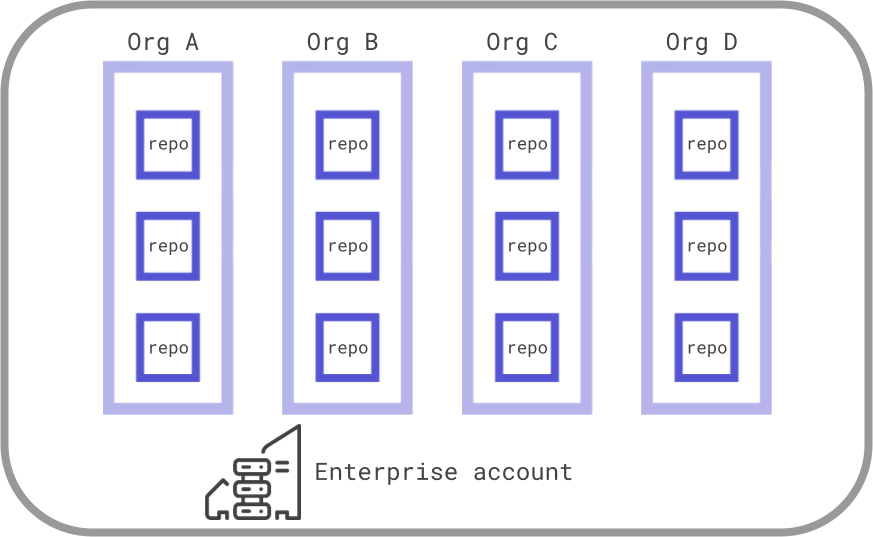

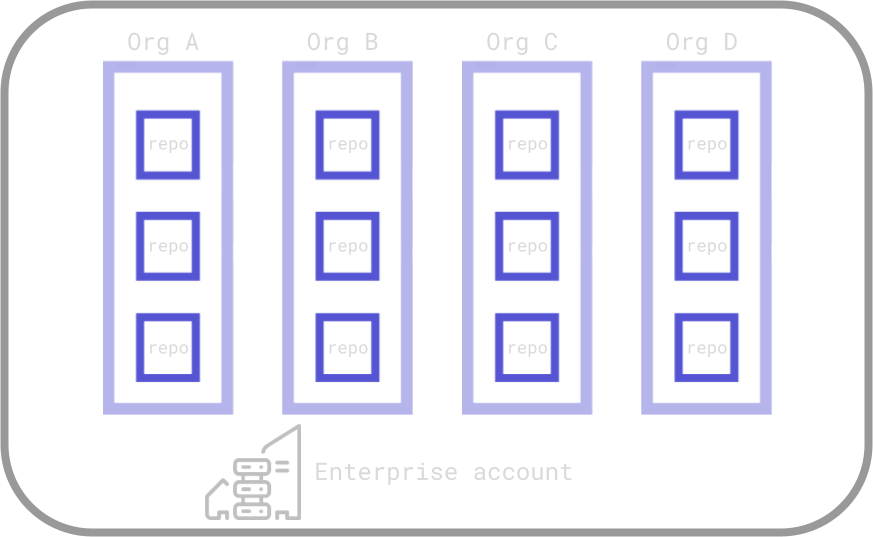

The diagram to the right shows the basics of what “doing less” could mean for builder images. It means having some specialization so they aren’t literally the entire tooling of every team in the company in one image. Each CI system (GitHub, GitLab, Jenkins, etc.) handles this a tiny bit differently, but the core idea of having a set scope for each image to do is the same across them all.

I compiled some architecture suggestions for self-hosting CI servers to provide a starting point on how to accomplish “doing less per image” and outline the cost/benefit analysis each. Here’s a few examples I’ve come across that work well:

- Separation by project - A company has 4 business units, each with multiple project teams. Each team builds, maintains, and secures their own infrastructure. It has simplicity from a people and management standpoint, as localized controls allow teams to best build what fits them.

- Separation by language/framework - Corporate maintains an inventory of images with minimal configurations (eg, pointing to a central maven/pip/npm repo, custom SSL certs, central log forwarding, etc.) for reuse by teams with additional customizations optional. Most folks I talk to have this as an ideal end state, as it balances both efficient use of specialized human resources to build/harden/operate without adding enough to an image to offset those human costs.

- Separation by task - Many teams in the same company have a similar task to scan their code for security vulnerabilities, perform acceptance testing, etc. Corporate maintains an image as “reusable pipeline” for those common tasks, regardless of language or project.

This pattern holds up well to many of the other uses we outlined above. It makes sense for worldwide multi-tenant SaaS platforms to have 30+ GB images for virtual machines, but that probably doesn’t make sense for teams with narrower scopes of work.

Wherever we find a big container, we can usually find a way to do less with any one part. Any of these allow your image to be able to do less without breaking things.

The example images

For our examples, we’ll (mostly) use the CI agents that we’ve been working on here. Some relevant numbers:

- 5 images for multi-purpose CI jobs

- 2 architectures built for each image (

arm64andamd64) - Multiple software packages installed in various ways (shell script, official package repo, etc.)

- Each is 1 to 1.4 GB in size

- A non-zero number of vulnerabilities (as of writing, current stats here )

The images are built from a variety of “base” images to provide similar functionality across different platforms. The code repository and writeups both have tons more information about the configuration, build scripts and testing suites, and much more about each one.

Why are they so big?

In short, they have the ability to do lots of things. The large size comes from two sources.

First, they’re “built” much like any other software. The container files (which we custom built and secured earlier) take a base image, run some commands to install software, copy in and run some scripts, etc. Each of these steps is a discrete layer in the final container. This allows reuse of any individual layer at the cost of perhaps duplicating size. It’s important to reduce package caches, remove installers and tarballs, and other “hygiene” tasks as you go, before moving on to the next layer of the image. Because the final size of a container is the compressed sum of these changes, anything with a halfway complicated build can get very large very fast.

how I really feel about big container images for CI

how I really feel about big container images for CI

Second, most build agents are pretty big! These handle a variety of workloads, each with their own dependencies. How your organization decides to handle breaking down the types of workloads, tolerance for caching or setup time, and the company security boundary is what allows you to have many small deployments or fewer larger deployments. At a massive scale for fewer-and-larger runners, both the GitLab and GitHub SaaS runners for Linux weigh in at tens of GBs of pre-loaded libraries. On the other end, there are plenty of self-hosted teams that have each discrete step in each of their builds handled by a unique agent specialized just for that step.

There are more tradeoffs in this calculation I spoke about here - in short, pick your battles. ⚔️

What’s in the image?

For my “simple and useful, yet easy to customize” idea, I have the following installed on each image (which adds around 1 GB to all):

- the GitHub actions/runner agent to actually do the job

- git, git-lfs, and gh (the GitHub CLI)

- bash

- unzip, wget, curl, wget, jq, and other small utilities

Some of the images have an additional couple hundred MB with kubectl, helm, and the docker CLI too. This allows them to orchestrate deployments of other containers.

🔬 These images, with their many possible uses and messy builds, will give us realistic scenarios to test ways to shrink the size of complex containers and how those tasks impact security.

“Do less” is quite good at reducing the size of each container. For build systems, it also improves the security posture by having less software in each image to inspect, patch, test, configure, etc. Fewer tasks/people/systems with access to any given thing means a reduced attack surface and lower CVEs.

🧹 Next up - Tidying up your container builds with some simple changes that can make a big difference. Part 2: Tidy big builds

Footnotes

-

I kinda maintain this still, mostly to simulate other workloads (eg, rapid scaling, eBPF data generation and sifting, build provenance demos, showing how other components work, etc) now than the actual thing it does (containerized GitHub CI). 🤷🏻♀️ ↩