Reducing CVEs in actions-runner-controller

It’s the same actions-runner-controller you know and love (or curse), but with many fewer CVEs to generate compliance paperwork. With a new gig and new tech stack to learn, let’s do something a little harder than a local Jekyll development container! 📚

This walkthrough replaces the default container of actions-runner-controller and then builds an Actions runner based on wolfi , lowering CVEs and improving the overall security posture. It’s also using the Kubernetes container mode , eliminating most use cases of privileged pods in actions-runner-controller. I’m adding it to kubernoodles to be used by the folks I used to and currently work with.

I’ve spoken a time or two about GitHub Actions with actions-runner-controller encouraging a pattern of using containers as VMs. This isn’t very “cloud native” to fling giant containers around, but it’s workable.

Let’s revisit that reference architecture to lower the CVE count of each runner, learn a little about distroless, and maybe help some folks out. Many of the runner images are currently well into the hundreds of CVEs each. I remember having to fill out spreadsheets and acknowledging each CVE individually with written plans to mitigate them … I don’t ever want to do that again. 🙈

By changing our base image, we can reduce CVEs for the runner image (from 134 to 7) (full chart)

The above data changes literally every day … check the runner list for information that’s updated weekly.

Let’s make this easy, so we can remain at a human-manageable level of security items to track moving forward without dedicating a ton of headcount towards smashing CVEs.

Where we’re going

- Build a new runner image based on [Wolfi], a container-purposed “distroless distro”

- Kubernetes mode 101 to eliminate most uses of privileged pods

- Deploy the runner with the new image

- Validate everything works as expected

- Compare CVEs between the new runners and existing runners in the project

A more secure GitHub Actions runner

For the impatient, here are links to the finished Dockerfile , Helm values.yml for actions-runner-controller as a runner scale set , and the finished container image . 🚀

Upfront considerations

The previous iterations of runners we’d built (ubi8, ubi9, and ubuntu-jammy) all resemble a traditional Linux server distribution because that’s really what they are. They even include an init system and package manager in the image. In many ways, that first custom image resembled building a virtual machine image rather than a container. This time, we’re going to be more prescriptive about the utilities we’re using, meaning that for larger deployments, you’ll have more deployments of smaller images rather than a few big ones.

1

2

3

4

# apk update

fetch https://packages.wolfi.dev/os/aarch64/APKINDEX.tar.gz

[https://packages.wolfi.dev/os]

OK: 53893 distinct packages available

The package manager is a little different, using Alpine’s apk for management and Wolfi’s own apk ecosystem . Being based on glibc (not muslc like Alpine) means packages can’t usually cross between the two without being recompiled. With over 50,000 packages available, it’s got reasonable coverage for whatever it is you’re wanting to do.

Despite the drastic shift in the base image and package ecosystem from our first custom image, the process of building the image is very similar. It’s only a couple of lines to change it, but to prevent the need to go back and forth between the two, let’s take it from the top!

Labels are still the best

🪄 That FROM line is most of the magic we need here. 🪄

Labels are still fabulously handy. Use as many as you’d like, especially the pre-defined ones that can help you correlate images to any other system across your company.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

FROM cgr.dev/chainguard/wolfi-base:latest

LABEL org.opencontainers.image.source="https://github.com/some-natalie/kubernoodles"

LABEL org.opencontainers.image.path="images/wolfi.Dockerfile"

LABEL org.opencontainers.image.title="wolfi"

LABEL org.opencontainers.image.description="A Chainguard Wolfi based runner image for GitHub Actions"

LABEL org.opencontainers.image.authors="Natalie Somersall (@some-natalie)"

LABEL org.opencontainers.image.licenses="MIT"

LABEL org.opencontainers.image.documentation="https://github.com/some-natalie/kubernoodles/README.md"

Put your arguments up top too

Next, your time is valuable. Conserve it by putting arguments near the top of the file for the software in the build that changes in arguments. This makes it easier to know where everything is defined to change the versions of the software you’re using.

Set up the non-root user to run jobs as too.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

# Arguments

ARG TARGETPLATFORM

ARG RUNNER_VERSION=2.329.0

ARG RUNNER_CONTAINER_HOOKS_VERSION=0.8.0

ARG DOTNET_VERSION=9

# Set up the non-root user (runner)

RUN addgroup -S runner && adduser -S runner -G runner

Install what you need

The list below is a reasonably minimal set of APKs to add to the image to do basic build tasks. This is likely where you’ll spend the most time per unique image deployment to manage. Some notes:

- ASP.NET is needed for the runner agent.

- Bash is generally helpful and most existing shell script workflow steps likely expect it.

- Docker CLI is needed to run container Actions. Even if they execute in another pod, this is how it’ll interact with them.

- git is needed to check out code.

-

ghis the GitHub CLI, handy but also a weirdly silent dependency in some marketplace Actions. - NodeJS is needed for Javascript Actions and for the container hooks to manage the pods for container Actions. We’ll also be replacing the versions bundled with the runner agent with the system version to further lower CVEs.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

# Install software

RUN apk add --no-cache \

aspnet-${DOTNET_VERSION}-runtime \

bash \

build-base \

ca-certificates \

curl \

docker-cli \

dumb-init \

git \

gh \

icu \

jq \

krb5-libs \

lttng-ust \

nodejs \

openssl \

openssl-dev \

wget \

unzip \

yaml-dev \

zlib

Set up the runner

Now set up the path and directory for the runner agent to use.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

RUN export PATH=$HOME/.local/bin:$PATH

# Shell setup

SHELL ["/bin/bash", "-o", "pipefail", "-c"]

# Make and set the working directory

RUN mkdir -p /home/runner \

&& chown -R runner:runner /home/runner

WORKDIR /home/runner

RUN test -n "$TARGETPLATFORM" || (echo "TARGETPLATFORM must be set" && false)

Install the runner

Install and set up the runner agent. In this case, we’re pulling it from GitHub.com, but it could just as easily be the version on your own server too.

1

2

3

4

5

6

# Runner download supports amd64 and x64

RUN export ARCH=$(echo ${TARGETPLATFORM} | cut -d / -f2) \

&& if [ "$ARCH" = "amd64" ]; then export ARCH=x64 ; fi \

&& curl -L -o runner.tar.gz https://github.com/actions/runner/releases/download/v${RUNNER_VERSION}/actions-runner-linux-${ARCH}-${RUNNER_VERSION}.tar.gz \

&& tar xzf ./runner.tar.gz \

&& rm runner.tar.gz

Symlink shenanigans

The runner agent bundles its own version of NodeJS, which can be a source of CVEs. We’re going to remove the bundled versions and symlink to the system version instead.

⚠️ This could break some workflows and marketplace Actions that rely on these versions exclusively!

1

2

3

# remove bundled nodejs and symlink to system nodejs

RUN rm /home/runner/externals/node20/bin/node && ln -s /usr/bin/node /home/runner/externals/node20/bin/node

RUN rm /home/runner/externals/node24/bin/node && ln -s /usr/bin/node /home/runner/externals/node24/bin/node

This links both node20 and node24 to whatever the latest version of nodeJS is. This works a lot of the time, but if you or anything you run relies on a specific version of node, this will need to be adjusted.

Install container hooks

Now place the container hooks where they need to be. These are the scripts used to manage the pods for container Actions.

1

2

3

4

# Install container hooks

RUN curl -f -L -o runner-container-hooks.zip https://github.com/actions/runner-container-hooks/releases/download/v${RUNNER_CONTAINER_HOOKS_VERSION}/actions-runner-hooks-k8s-${RUNNER_CONTAINER_HOOKS_VERSION}.zip \

&& unzip ./runner-container-hooks.zip -d ./k8s \

&& rm runner-container-hooks.zip

Set up the environment

Set a few environment variables to make life a little easier to debug failures (log to stdout) and to trap signals to shut down the runner gracefully. Then switch to the runner user and ship it! 🚢

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

ENV RUNNER_MANUALLY_TRAP_SIG=1

ENV ACTIONS_RUNNER_PRINT_LOG_TO_STDOUT=1

# configure directory permissions; ref https://github.com/actions/runner-images/blob/main/images/ubuntu/scripts/build/configure-system.sh

RUN chmod -R 777 /opt /usr/share

USER runner

Build it

One major simultaneous-feature-and-limitation of Wolfi - the base image and package repository are all latest at all the times. This means that we should build frequently, but tag with the date it’s built as the halfway canonical source of truth in versioning. Each image could change versions of the software inside at each build, so this is the only freely-available control we have on what’s inside. To control the versions of the software inside (or use FIPS-validated cryptography), you’ll need to use chainguard-base instead. Apart from the availability of versioned components, the build process and compatibility are the same.

Let’s be boring with a quick local build and push. For longer-term use, here’s the workflow file I use that’ll also scan and sign the image too.

A quick detour into Kubernetes mode

In order to run container Actions, we have two options - we can allow nested containers (eg, Docker-in-Docker) which requires privileged execution of a pod, or we can allow one pod to spin up another for the container Action. We’re doing the latter, so pause to create a service role to do this . For convenience, the role is defined entirely below.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

# this is the role needed for container hooks

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: Role

metadata:

namespace: default # yeah, change this to the namespace you're using

name: runner-role # this is alright though

rules:

- apiGroups: [""]

resources: ["pods"]

verbs: ["get", "list", "create", "delete"]

- apiGroups: [""]

resources: ["pods/exec"]

verbs: ["get", "create"]

- apiGroups: [""]

resources: ["pods/log"]

verbs: ["get", "list", "watch",]

- apiGroups: ["batch"]

resources: ["jobs"]

verbs: ["get", "list", "create", "delete"]

- apiGroups: [""]

resources: ["secrets"]

verbs: ["get", "list", "create", "delete"]

The role above allows the container hooks we installed above to manage pods for container Actions called by the runner. Both the “parent” and “child” run without privileged execution.

Deploy the runner

Now that we’ve got the image and the controller set up, let’s deploy the runner. The Helm chart is the same as before, but with new values. This time, it’s using Kubernetes mode instead of nothing (the ubi9 or ubi8 runners) or Docker-in-Docker (like the rootless-ubuntu-jammy runner). Here’s the new values file :

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

githubConfigUrl: "https://github.com/some-natalie/kubernoodles"

githubConfigSecret:

### GitHub Apps configuration (for org or repo runners)

github_app_id: ""

github_app_installation_id: ""

github_app_private_key: |

-----BEGIN RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

key-goes-here

-----END RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

### GitHub PAT configuration (for enterprise runners)

# github_token: ""

maxRunners: 5

minRunners: 1

# runnerGroup: "default"

template:

spec:

containers:

- name: runner

image: ghcr.io/some-natalie/kubernoodles/wolfi-runner:test

command: ["/home/runner/run.sh"]

securityContext:

runAsUser: 100

runAsGroup: 100

env:

- name: ACTIONS_RUNNER_CONTAINER_HOOKS

value: /home/runner/k8s/index.js

- name: ACTIONS_RUNNER_POD_NAME

valueFrom:

fieldRef:

fieldPath: metadata.name

- name: ACTIONS_RUNNER_REQUIRE_JOB_CONTAINER

value: "false" # allow non-container steps

volumeMounts:

- name: work

mountPath: /home/runner/_work

containerMode:

type: "kubernetes"

kubernetesModeWorkVolumeClaim:

accessModes: ["ReadWriteOnce"]

storageClassName: "local-path" # use your real storage class here

resources:

requests:

storage: 1Gi # this may need to change based on the workload

limits:

storage: 5Gi # this may need to change based on the workload

And it’s every bit as simple to deploy as the other runners!

1

2

3

4

5

helm install wolfi \

--namespace "ghec-runners" \

-f local-wolfi.yml \

oci://ghcr.io/actions/actions-runner-controller-charts/gha-runner-scale-set \

--version 0.13.0

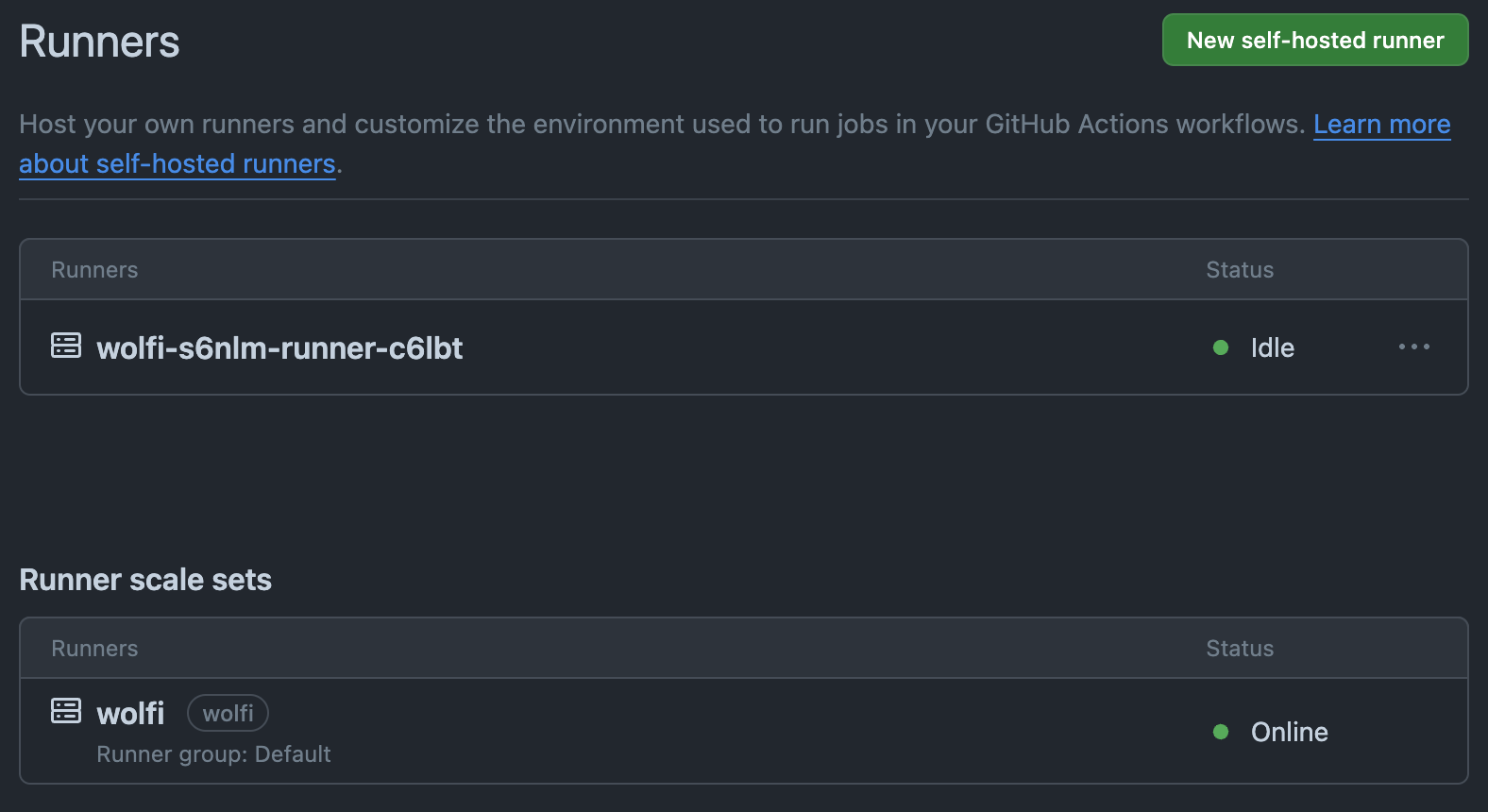

Make sure everything is pointing to the latest version, as the free Chainguard images are only latest. A version mismatch between the controller and the listener can cause issues. But assuming everything matches up, the new scale set should be idle in the self-hosted runner group.

Validation

As we talked about in threat modeling GitHub Actions, an Action is one of three things:

- Javascript - Either a separate repository of Javascript with bundled dependencies to run or some small bit of code to run in line. This test workflow file checks both.

- Container - Running these safely is why we set up Kubernetes mode to begin with. These can be a prebuilt container to pull on each run (works!) or a Dockerfile built on each run (will not work with k8s mode, must use Docker-in-Docker). This is the test workflow that will cover what we need.

- Composite - This catch-all category is anything else, like a shell script or a Python script. This test workflow are the composite steps we’re testing on each build.

Our runner test suite hasn’t changed since we last left it, so it now runs for this new image too.

CVE comparison

It’s once we start comparing the runner images that the count of CVEs to inventory and manage becomes problematic. The spread here is from 0 to well over 500, with the majority of the CVEs being medium or below. The wolfi image is the lowest, with zero CVEs to account for.

| Image | (total) | Critical | High | Medium and below |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ghcr.io/actions/actions-runner:2.327.1 | 134 | 0 | 18 | 116 |

| ghcr.io/some-natalie/kubernoodles/wolfi:latest | 4 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| ghcr.io/some-natalie/kubernoodles/ubi8:latest | 658 | 0 | 9 | 649 |

| ghcr.io/some-natalie/kubernoodles/ubi9:latest | 632 | 0 | 9 | 623 |

| ghcr.io/some-natalie/kubernoodles/ubi10:latest | 236 | 0 | 23 | 213 |

| ghcr.io/some-natalie/kubernoodles/rootless-ubuntu-jammy:latest | 276 | 0 | 16 | 260 |

| ghcr.io/some-natalie/kubernoodles/rootless-ubuntu-numbat:latest | 227 | 0 | 15 | 212 |

The CVE counts are as of 11 August 2025 and will change as new vulnerabilities are discovered and patched, images rebuilt, etc. The

latesttag the most recent build to date for Kubernoodles. The CVE counts are from the Grype scan (v0.97.2) run on the images listed above.

Why

Most teams do not have the time to enumerate, track, and understand 500+ CVEs per image - much less the time to start mitigating them. In having large containers with many components, it’s easy to get out of hand with CVEs. Nonetheless, hiding them or ignoring them only helps them multiply. They’re like tribbles in that way. 🐹

Developing runner images are in a central-to-the-company repository to manage the changes, builds, and deployments within actions-runner-controller keeps a good inventory of what’s running where. This is a critical part of many compliance frameworks. It also lowers the additional work associated with a new runner, allowing teams some autonomy to ship what they need without a ton of extra risk. This pattern of smaller images to do single tasks reduces the blast radius of any one image and lowers overall CVE toil.

Disclosure

I work at Chainguard as a solutions engineer at the time of writing this. All opinions are my own.