Creating custom images for actions-runner-controller

Now that we have actions-runner-controller up and running, we need to think through the runner image some. This piece is all about how to build your own image(s) and whether it’s a good idea to do that.

The end result of this how-to is an image based on UBI 9 that has no

sudorights. This means container-y things won’t work and users cannot modify the base image (which could be great or awful).⚠️ This image has 23 high CVEs, plus hundreds of medium and below security vulnerabilities (as of August 2025). Need to lower that? Reducing CVEs in ARC should help!

🚢 If you’re impatient, here’s links to the finished Dockerfile , Helm values.yml for actions-runner-controller as a runner scale set , and the finished image . We’ll cover a Docker-in-Docker container build later.

All about the default runner image

There’s a default runner image for use that is maintained by GitHub. It’s very minimal and might suit your needs. It’s based on the Microsoft container image for .NET, which is based on Debian. It adds the actions/runner agent, the container hooks , and Docker to run container Actions. The extraordinarily thoughtful ADR1 is here and it’s worth reading several times over. (Dockerfile and image registry )

This could be problematic for a few reasons.2

- The

runneruser has sudo rights. This allows users the flexibility to modify the image to build their code, automate the toil, and all the other cool stuff that can be done with Actions - drastically reducing the number of bespoke images to maintain for each project. This maintenance savings comes at the price of giving users a shell with root access in a pod. - It’s based on Debian - this is fine for platform neutral stuff, but if you’re in the Red Hat ecosystem doing things specific to that, it’s less than ideal. Ditto for other Linux ecosystems, but Red Hat is the one I see most frequently.

- Because the image has so few things cached and installed inside of it, at scale, running

docker pullorapt install(etc) starts to really eat at your network ingress budget and cause long build times by pulling/installing the same software all the time.

There are a lot of trade-offs to consider as you design and build this for your company’s infrastructure. The entire point of Kubernoodles is minimizing the cost of building and running custom images in actions-runner-controller with a few key ingredients to achieve 🌈 DevSecOps magic 🌈

- 💖 love and respect for your developers and security team

- 🤖 automating ALL THE THINGS

- 💸 knowing what gets expensive

To make an initial image, we’re going to need a laptop or workstation with a container runtime (e.g., Docker Desktop or Podman Desktop ). We’ll set up GitHub Actions to build and scan and sign and ship and all that jazz for its’ own runners in the next part.

Choose your base image

First things first, we need to choose our base image. If you have an internal “baseline” image that’s kept reasonably3 up to date, just use that. It likely already has an opinion on baseline configurations. The only other trap to watch out for is most “hardened baseline” images remove root/sudo rights, limiting all modifications that can be done by admins before we ship this thing to users. If not, I strongly recommend using a boring, official(!!) base image such as:

We’re going to use a freely4 available Universal Base Image (UBI) from Red Hat. It requires no license or fees to use. It’s kept updated and healthy by a corporate sponsor and it’s close enough to regular Red Hat Enterprise Linux that you can change the target out pretty quickly if needed. In exchange, the package ecosystem doesn’t contain as many things as regular RHEL. More about the UBI images here . It also has a library of compliance standards for “hardening” it or creating some sort of “secure baseline”. In short, no one gets fired for choosing UBI images.5

I tend to not recommend using the ever-popular Alpine distribution for this use case. While it can do many things extremely well, being built from the ground up to be run as a container, it also can cause a ton of paper-cuts for developers in a large enterprise that haven’t built their software to run in it. The dependency on musl libc causes lots of weird build failures in software expecting other C standard libraries, as does a more limited availability of legacy software in their package ecosystem . It can be done, but I question if it’s worth the effort.

Regardless of which base you choose, I’m a huge fan of broad tags on the base image - such as ubuntu:numbat for Ubuntu 24.04 LTS. These trusted images are updated frequently and those tags get pushed accordingly. This means that ubuntu:numbat will always hit a reasonably updated image. This causes concerns around build idempotency that we’ll address in the tagging section further down.

One final consideration on your base image - please use an init system for your containers used as runners for GitHub Actions. Fundamentally, a container is a normal process with some fancy-pants guardrails around it for isolation (cgroups, kernel capabilities, etc.). This pattern works fantastically for single-process containers - it’s what it was designed to do! However, a runner for GitHub Actions has multiple processes in that single container by design. It will be running, at the very minimum:

- The runner agent (actions/runner ), for receiving jobs from GitHub and sending data/results back.

- Whatever that job entails - build your code, scan/lint/whatever some code, run some script, start a container or ten, other automation tasks, etc.

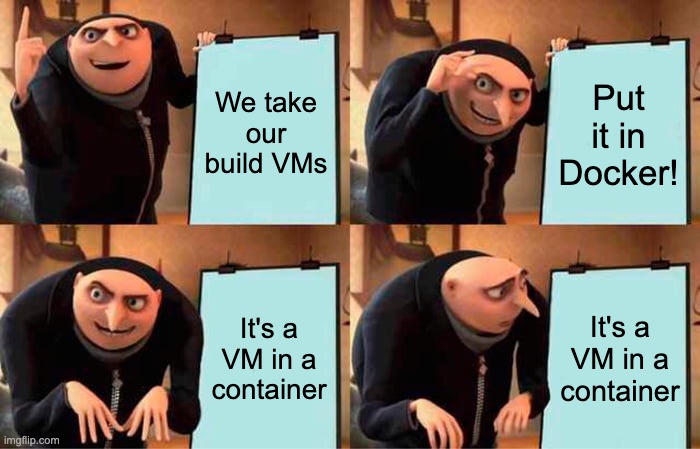

What we really want to be able to do is have these “fat containers” be treated as a regular Linux process by the worker nodes in Kubernetes. Actions-runner-controller treats containers as VMs because GitHub Actions assumes the base compute for things is a virtual machine - running general purpose build infrastructure in containers usually ends up with this pattern. An init system provides a lightweight and simple abstraction to allow Kubernetes to manage these containers, the worker nodes to reap processes as expected, and developers to not rework their entire workflow to run in containers. I recommend the following:

- The pre-built

ubi-initimages for UBI (Documentation ) - Yelp’s

dumb-initproject (GitHub and blog announcement ) to add into other base images. -

tini(GitHub ) is built-in to Docker when you use the--initflag, also a great minimal init system.

Here’s our code snippet with the base image for this example.

1

FROM registry.access.redhat.com/ubi10/ubi-init:10.0

Labels are the best

Container labels are literally ✨ free glittery goodness ✨ bestowed upon us by our YAML overlords. Use them liberally. These lightweight key/value labels allow you to build all sorts of other processes out on top of these containers, such as:

- Documenting what the source and documentation of the image is

- Adding authorship, licensing, and other descriptive data (if needed)

- Integrating with all sorts of other tools in the container ecosystem that rely on custom metadata

Defining almost anything you want is the entire point of labels . However, the Open Container Initiative has defined a bunch of standard keys for your values here . The ones I use (with my values, not yours) are below.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

LABEL org.opencontainers.image.source="https://github.com/some-natalie/kubernoodles"

LABEL org.opencontainers.image.path="images/ubi10.Dockerfile"

LABEL org.opencontainers.image.title="ubi10"

LABEL org.opencontainers.image.description="A RedHat UBI 10 based runner image for GitHub Actions"

LABEL org.opencontainers.image.authors="Natalie Somersall (@some-natalie)"

LABEL org.opencontainers.image.licenses="MIT"

LABEL org.opencontainers.image.documentation="https://github.com/some-natalie/kubernoodles/README.md"

For your own internal images, make sure to at least set the documentation field to where your users can learn more. Ideally, use innersource patterns to make the source code of your images available to your users so they can understand what’s going on in their build compute, make changes, etc. The source field can tell them that.

Making some arguments

The next bit of code in our Dockerfile places all the arguments that get updated regularly near the top of the file. This information can be elsewhere in the file, but putting it up front means it’s easier to see and update regularly.

The first two arguments go into installing actions/runner later in the file - telling it which target architecture and release to use. The last one is for runner-container-hooks , which is optional and I’m including for reasons we’ll go into later.

1

2

3

4

# Arguments, allowing TARGETPLATFORM to be set at build time

ARG TARGETPLATFORM

ARG RUNNER_VERSION=2.329.0

ARG RUNNER_CONTAINER_HOOKS_VERSION=0.8.0

I like to bundle any other similar arguments together here too, such as versions of other software to include. Keeping it together means I don’t hunt through long Dockerfiles to update it - I want my “future me” to like “present me” as much as possible.

Get notified about new releases from repositories used upstream from your images by following these directions .

Some basic setup

A couple boring items to set up now. First, we’re going to be using some shell pipes later on in this file, so let’s tell our container how to handle them properly - otherwise Hadolint will complain at us (DL4006 , if you’re interested).

1

2

# Shell setup

SHELL ["/bin/bash", "-o", "pipefail", "-c"]

Next, only for UBI images assuming we want to maintain some compatibility with OpenShift or OKD , a couple items:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

# The UID env var should be used in child Containerfile.

ENV UID=1000

ENV GID=0

ENV USERNAME="runner"

# This is to mimic the OpenShift behaviour of adding the dynamic user to group 0.

RUN useradd -G 0 $USERNAME

ENV HOME /home/${USERNAME}

Lastly, if you have to configure custom internal repositories or certificate authorities or other such fun in order to proceed, copy those files in before continuing.

Runner agent setup

Now let’s set up the runner agent. That thoughtful ADR on the runner image (here ) specifies what’s assumed to be where / how / etc. for custom images. This will look a little different for Debian-based images, using apt instead of dnf, but should still be a copy/paste exercise.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

# Make and set the working directory

RUN mkdir -p /home/runner \

&& chown -R $USERNAME:$GID /home/runner

WORKDIR /home/runner

# Runner download supports amd64 as x64

RUN export ARCH=$(echo ${TARGETPLATFORM} | cut -d / -f2) \

&& if [ "$ARCH" = "amd64" ]; then export ARCH=x64 ; fi \

&& curl -L -o runner.tar.gz https://github.com/actions/runner/releases/download/v${RUNNER_VERSION}/actions-runner-linux-${ARCH}-${RUNNER_VERSION}.tar.gz \

&& tar xzf ./runner.tar.gz \

&& rm runner.tar.gz \

&& ./bin/installdependencies.sh \

&& dnf clean all

The runner container hooks are needed to allow the container to use k8s jobs instead of Docker-in-Docker, so optionally add the following to use them:

1

2

3

4

# Install container hooks

RUN curl -f -L -o runner-container-hooks.zip https://github.com/actions/runner-container-hooks/releases/download/v${RUNNER_CONTAINER_HOOKS_VERSION}/actions-runner-hooks-k8s-${RUNNER_CONTAINER_HOOKS_VERSION}.zip \

&& unzip ./runner-container-hooks.zip -d ./k8s \

&& rm runner-container-hooks.zip

Choose your own adventure

Now we’re to the point of customizing everything, so less copy/paste and more thoughtful consideration of a few things. 😅

To sudo or not to sudo

The UBI image doesn’t include sudo, so I did no extra work to include it in this example. If you want to allow users to run privileged commands inside the runner container (to, say, modify their build environment every run), here’s how you’d do that. Install the sudo package with your package manager, then add them to the sudo or wheel group. For a Debian-based system, this is what that looks like:

1

2

3

4

# Runner user

RUN adduser --disabled-password --gecos "" --uid 1000 runner \

&& usermod -aG sudo runner \

&& echo "%sudo ALL=(ALL:ALL) NOPASSWD:ALL" > /etc/sudoers

Installing software

Assuming we’re not allowing sudo or just want to keep our ingress bandwidth charges reasonable, here’s where software gets installed. There’s two broad-ish categories - stuff included in your package manager’s ecosystem and stuff that isn’t.

For the things in the ecosystem, let’s update the cache, install git and jq, and clear that cache. Add as many packages as you need here - dnf and most other modern package managers are smart enough to install the needed dependencies.

1

2

3

4

5

RUN dnf update -y \

&& dnf install -y \

git \

jq \

&& dnf clean all

Now for things not in the package ecosystem, I like run the commands in-line if it isn’t complicated or is managed in another repository.

1

2

3

4

5

6

# Install helm using the in-line curl to bash method

RUN curl https://raw.githubusercontent.com/helm/helm/main/scripts/get-helm-3 | bash

# Use an install script to install the `gh` cli, more about that below!

COPY images/software/gh-cli.sh gh-cli.sh

RUN bash gh-cli.sh && rm gh-cli.sh

If there’s more configuration to be done or the script is managed in the same repository, I like the copy/run/remove pattern. Install scripts allow for discrete version-controlled management of the dependencies, configuration, if/else cases, etc. in the same repo, but at the expense of an additional layer in the finished image. Here’s an example using a simple if/elif/fi loop:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

#!/usr/bin/env bash

if grep -q "Ubuntu\|Debian" "/etc/os-release"; then

curl -fsSL https://cli.github.com/packages/githubcli-archive-keyring.gpg | gpg --dearmor -o /usr/share/keyrings/githubcli-archive-keyring.gpg

echo "deb [arch=$(dpkg --print-architecture) signed-by=/usr/share/keyrings/githubcli-archive-keyring.gpg] https://cli.github.com/packages stable main" | tee /etc/apt/sources.list.d/github-cli.list > /dev/null

apt-get install dirmngr -y

apt-get update

apt-get install gh -y

apt-get autoclean

apt-get autoremove

rm -rf /var/lib/apt/lists/*

elif grep -q "CentOS\|Red Hat" "/etc/redhat-release"; then

yum-config-manager --add-repo https://cli.github.com/packages/rpm/gh-cli.repo

yum install -y gh

yum clean all

fi

Caching stuff

One of the most common friction points as your user base scales is caching dependencies correctly. The assumption is that these are images that are transferred between an internal registry and an internal Kubernetes cluster, so we are minimizing our ingress bandwidth at the cost of flinging around larger container images. There’s two types of caching to consider - pointing the runner at the correct internal caches and adding files to the image itself.

The first is simple - configure each package ecosystem to point to the company’s internal package registry. Do this in the container’s build and don’t worry about it again. It’ll grab the blessed versions of whatever the user needs.

The second is tricky in that you’ll have to find a balance between the number of images to maintain and the size of those images. If you were to rebuild the Ubuntu VM image for GitHub Actions, it’d end up at over 50 GB in size - while technically possible, it’s very unwieldy as a container. A single container this large is slow to spin up and rather wasteful. On the other hand, maintaining dozens of bespoke images does nothing to improve your team’s sanity or time utilization.

Here’s the most common things to cache:

-

Offline tools - When a user runs one of the

setup/languageActions in a job (example ), that job is dispatched to a runner, the runner downloads the Action from GitHub, then reads that it will want to download the specified versions of that language. It checks a local cache (usuallyRUNNER_DIR/_work/_tool), then attempts to download what it needs from the internet. - Container images - if you are doing container things inside of your runner container, you can usually run a

docker pullto pull the needed build dependencies up front, making a larger image that pulls from your internal registry less frequently. - Common tooling across projects/teams - things in this space include code scanning applications, “paved path” or blessed languages (eg, always use

<languages>and nothing else), or common shell utilities.

In all of these situations, allowing the worker nodes to hold on to pulled images will make these large containers reasonably performant. The image pull policy is set to ifNotPresent by default in the helm charts.

Other considerations

The other thing to consider is how to go about storing and collaborating on this project. I recommend working these images and the files used to create them as an internally visible repository - building a framework for users to request more/different/changed deployments in a central location. It also allows your administrators, auditors, all integrations, etc. to flow to a “single pane of glass” for visibility. Monorepos work quite well for this use case.

Moving off latest

Using the latest tag is fine for building and testing without real users. Let’s move to a sane tagging strategy.

I’ve written previously about using a combination of semantic versioning and date-based tagging for this use case. I stand by this as a human-friendly way to keep track of two very different data points that combine for the end image - changes in software or other architecture bump the semver, but routine rebuilds bump the date. This allows the runner to receive security updates on a more frequent basis, but also track builds that may change and require more idempotency than many (most?) software projects.

At any rate, don’t use latest for real life. There is no torture quite like trying to respond to an audit or troubleshoot a failed build when you have no idea what was actually in use, where, and by what processes. ✨ Be kind to future you. ✨

Building and deploying manually

Now build and push that image from our workstation. Don’t make this complicated. Using Docker from your workstation, here’s what that looks like (substituting your filenames, registry paths, etc.):

1

2

docker build -f images/ubi10.Dockerfile -t ghcr.io/some-natalie/kubernoodles/ubi10:latest .

docker push ghcr.io/some-natalie/kubernoodles/ubi10:latest

And here’s the super basic values for the Helm chart:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

## githubConfigUrl is the GitHub url for where you want to configure runners

## ex: https://github.com/myorg/myrepo or https://github.com/myorg

githubConfigUrl: ""

githubConfigSecret:

### GitHub Apps Configuration, IDs MUST be strings, use quotes

github_app_id: ""

github_app_installation_id: ""

github_app_private_key: |

-----BEGIN RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

key goes here

-----END RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

### GitHub PAT Configuration

# github_token: ""

## maxRunners is the max number of runners the auto scaling runner set will scale up to.

maxRunners: 5

## minRunners is the min number of runners the auto scaling runner set will scale down to.

minRunners: 1

template:

spec:

containers:

- name: runner

image: ghcr.io/some-natalie/kubernoodles/ubi10:latest

command: ["/home/runner/run.sh"]

And how to apply it:

1

2

3

4

5

helm install ubi10 \

--namespace "runners" \

-f local-private-ubi10.yml \

oci://ghcr.io/actions/actions-runner-controller-charts/gha-runner-scale-set \

--version 0.13.0

Now check that the single pod is up and listening.

1

2

3

$ kubectl get pods --namespace runners

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

ubi10-2tg6n-runner-pm7z6 1/1 Running 0 1m

Lastly

Yeah, this is 20 minutes (more? less?) in and we’re using containers as VMs. It’s less than cloud native, not what containers were really designed to be doing, and it works pretty well. 🤷♀️

Next - a small detour into building containers without --privileged, then how to move this build into GitHub Actions so it’ll build/test/deploy itself!

Footnotes

-

ADR stands for Architecture Decision Record. It’s used to document a design problem, why it was approached the way it was, and any alternatives considered. You can read more about them at adr.github.io . ↩

-

This used to have a section on Docker-in-Docker, as it was more typical to have one container do this too. Now ARC supports having a DinD capable container within the pod (usually docker:dind ). That’ll still need to be run as a privileged pod (previously discussed here and here as to why that’s probably not a good idea). However, it’s now a much more explicitly created choice. ↩

-

What’s reasonable here is really up to you - but this pattern lends itself quite readily to ancient versions of “approved and hardened” images that don’t get ever get updated (and fall out of their compliance standard for being so “secure”). ↩

-

Free as in beer , anyways. More about redistribution and licensing and such at Red Hat’s site. ↩

-

To be perfectly honest, I spent several hours trying to find the origin of the phrase “nobody ever got fired for buying IBM”, and I couldn’t find a definitive answer. It’s been around for decades, though. ↩