Securing Self-Hosted GitHub Actions with Kubernetes and Actions-Runner-Controller

GitHub Actions is one of the most popular CI tools in use today. If you need or want to run it yourself, though, there are a lot of design choices to make and not a lot of guidance. The most popular choice is actions-runner-controller , an open-source project to manage and automatically scale the runner agents in Kubernetes. That still leaves a lot of questions with security implications, outlined in this post as slides + commentary from a talk I gave at CloudNativeSecurityCon North America 2023 in Seattle, WA.

🎥 YouTube video if watching a video is more your speed!

Introduction

Self-hosted GitHub Actions runners and Kubernetes are a natural fit, but there’s not a lot of guidance on how to put the two together. The leading solution is actions-runner-controller , an open-source community project which provides a controller for autoscaling, ephemeral, and version-controlled compute. It does not, unfortunately, show off how to design and deploy it securely.

I work with our most regulated and security focused user communities, having led one myself. This is a fun intersection of security, technology, and compliance - so let’s talk about developer enablement and secure, scalable containerization for CI, specifically actions-runner-controller .

This is where I’ve seen problems, weird edge cases, and security not considered as companies look to adopt actions-runner-controller across the spectrum of maturity in container adoption - from understanding why a company would choose this path, how it’s different than other applications you’d consider running within Kubernetes, and guidelines to consider in addition to existing best practices of container or Kubernetes security.

I’m sorry to disappoint if you jumped in here with the impossible expectations of “with this 1 YAML file, you’ll be totally unhackable”. That’s just not how this works … 😅

My career experience leads me to a bias. Friction, the force of resistance to movement between two parties, is the leading cause of users, admins, and developers doing insecure things. Eliminating any friction where security concerns are involved will inherently lead to (proportionately) fewer insecure things.

Why would you ever self-host?

We’re not here to talk in-depth about GitHub Actions as such, but there’s a few things we should all know. It’s our built-in automation platform, usually talked about in the context of continuous integration and delivery. If we’re being a bit too honest, it automates most of GitHub as well.

When a user on GitHub.com “just uses Actions”, they’re getting a ton of engineering that’s designed to be totally invisible. GitHub’s hosted runners are ephemeral virtual machines with a bunch of dependencies pre-loaded. The images are open sourced in this repository . They also are updated about once a week, scaled, managed, etc. for you. Caching and network presence is also handled magically. It’s a pay-as-you-go service to use, with some account entitlements and rates based on compute size (more here ). When users think “GitHub Actions”, this is normally the experience they’re expecting - being able to customize software and configurations at runtime, having privileged access, and access to a marketplace of prebuilt pipeline “building blocks”.

You can bring your own compute and it’s free - well, free-ish. Users still pay for datacenter colocation or commodity cloud compute. The agent to dispatch jobs between GitHub and that compute is free to use and open-source here . This can be installed on physical hardware, on virtual machines, or (as we’re talking about today) Kubernetes workloads. The tradeoff is that all of the operations of that compute is on you1. This is an uneven and often unexpected burden on security operations.

Not everyone has the option of using a SaaS to begin with. Here’s some common reasons for self-hosted runners:

- GitHub Enterprise Server - if you self-host GitHub, you have to also self-host the runners for it to use.

- Custom hardware - things like GPU or other special-use devices, CPU architectures like ARM, or testing hardware itself.

- Custom software - GitHub’s hosted runners allow users to install/modify the software on each run or run jobs within containers, but that doesn’t cover everything.

- “Gold load” type combinations of hardware and software. It’s difficult to simulate this.

- Because you want to and ✨ I’m not here to judge you ✨

Kubernetes is used for the same reasons as you’d containerize and orchestrate any other workload – it’s phenomenally good at it!

- Utilize in-house expertise and infrastructure

- Flexible deployments – enabling lots of discrete needs and user groups

- Easy ephemerality – a joy to work with and make reproducibility easier

- Simple version control on your build environment

- Vertical scaling allows small tasks to have small compute, large tasks can have more resources

- Horizontal scaling makes it uniquely powerful for lots of parallel jobs – Actions are parallel by default

So we need a controller for all this magic.

Enter actions-runner-controller , an open-source community driven project that’s also now the official auto-scaling solution for self-hosting Actions runners! 🎉

As a note, there’s currently a bunch of work going on in that project right now. This architecture diagram and the exact CRDs it implements will still be available. However, with the additional work for a better scaling solution adding a supported path, here’s a high-level overview that’ll age a bit better - automatic scaling is pull-driven over APIs. In the current implementation, that’s a pretty short (but configurable) poll length. There’s also an option for push-driven scaling via webhooks. The newer implementation will use a longer poll on a new API.

You can find an overview of the new CRDs and architecture diagram in the documentation . In any case, users are responsible for much of the infrastructure - from operations to security.

Given the variety of software development - tools and languages and platforms, etc - it’s hard to provide opinionated guidance or a set of “standard” images to use in Kubernetes. The GitHub-hosted ubuntu-latest image is about 50 GB, which would be quite an unwieldy container image. As the SaaS offering is a virtual machine, users are also allowed to use sudo, modify software, and do other things that are much riskier in a container.

One key security challenge around that user expectation is that it enables an anti-pattern where containers are used in very “VM-like” ways. Fewer, larger container images don’t need software modification at runtime (at least as often). Images capable of multiple “generic tasks” increases both the true vulnerability area and the false-positive “noise” generated by whatever tool in use to scan containers - making it hard for the team to know where to invest time.

The next hard security challenge is the economic incentives that encourage poor security posture, especially among smaller or less experienced teams. What I mean here is that running a build system in and of itself doesn’t bring in money to the company. There’s not a lot of reason to spend time doing this securely. Because of this, I see quite a few installations with a handful of common threat models that we’ll talk more about in depth as we go.

- Poorly scoped permissions or deployments - Managing fewer and broader things means some people in that group may have more permission or access than needed.

- Privileged pods - It’s usually more expedient to grant a deployment the ability to run as root than it is to rewrite parts of the software build to use containers safely.

-

Disabling or unsafely altering key security features - Things like SELinux, AppArmor, and seccomp exist for a reason - isolating processes safely. Just because StackOverflow says to just run

sudo setenforce 0(putting SELinux in audit-only mode) doesn’t mean it’s a good idea. -

Using

latestto deploy images - Not only is it hellishly hard to track who’s running what/where/when, it’s impossible to accurately fill out an incident report, understand which vulnerabilities correspond to which image versions, and just … don’t ever uselatestplease. -

Upstream repository mirrors that are wildly out of date - I get it, after the whole left-pad incident of 2016 and a bunch of other related shenanigans, running your own

<everything repository>internally became super popular. Understanding the dependencies of your software, in full, is a fantastic way to increase the security of your company’s code. There’s a ton of other good reasons to do this, but please remember that your<everything repository>requires regular care and feeding to be safe and not just harbor a ton of old vulnerable dependencies. ♥️

To understand why these challenges are a bit unique to using Actions within Kubernetes, let’s take a tiny detour into what GitHub Actions really are.

A quick detour into GitHub Actions

Going back to the theme of reusable open-source pipeline building blocks and “SaaS-y magic”, one doesn’t truly need to understand what’s inside any of the nearly 17,000 entries in the Actions marketplace in order to use them. You should treat this like any other software dependency, but that’s another talk for another day.

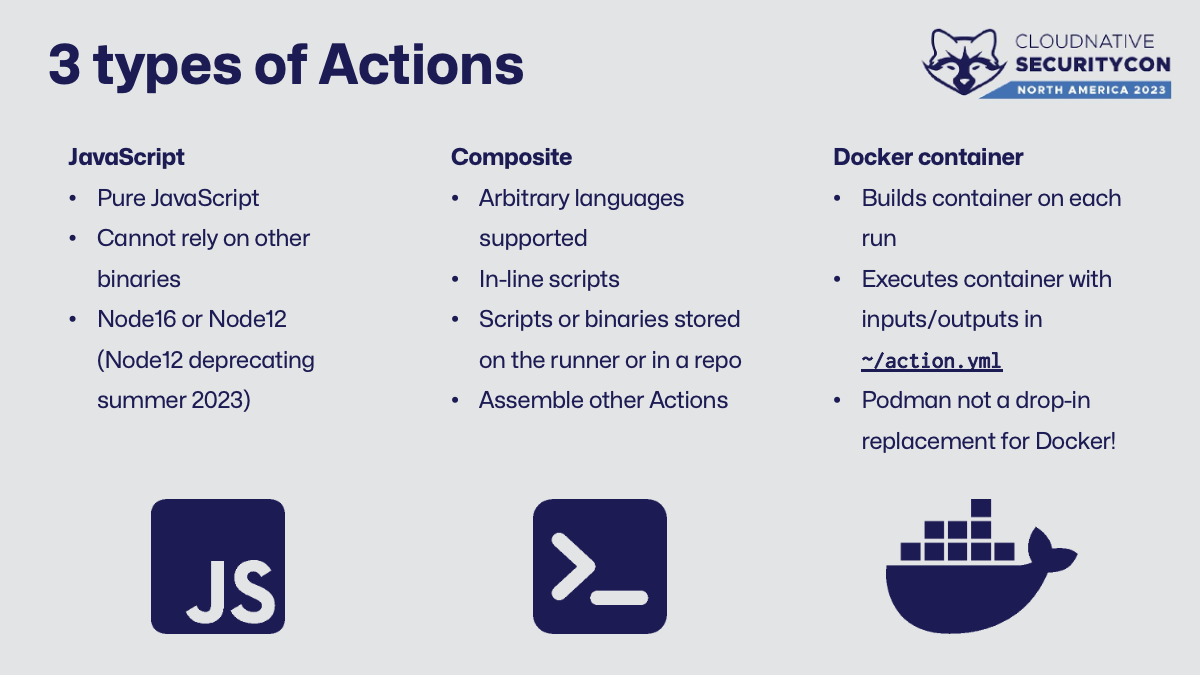

This is the first point of “oh, this gets tricky and weird in Kubernetes”. Behind the scenes, an Action can be one of three things that all have different security implications in a container versus a VM.

- JavaScript (docs ) - should be pure JS and no fancy shenanigans like calling additional binaries, etc. Supports Node16, Node12 is deprecating very soon. Runs more or less wherever you can run JavaScript.

- Composite (docs ) - seems like a bit of a “catch-all” category because it is. You can run arbitrary scripts in-line/directly, call binaries on the host, chain multiple other Actions together, etc. When I think of “reusable CI pipeline”, this is the closest analogy I get to.

- Docker (docs ) - builds and runs a container from a

Dockerfilewith the inputs and outputs defined in the Action. It’s almost like “serverless” if you squint. Important to note is that it expects Docker specifically and Podman isn’t always a drop-in replacement.

This means as we’re modeling threats and figuring out a more “enterprise-y” policy, there’s a lot more stuff to be aware of.

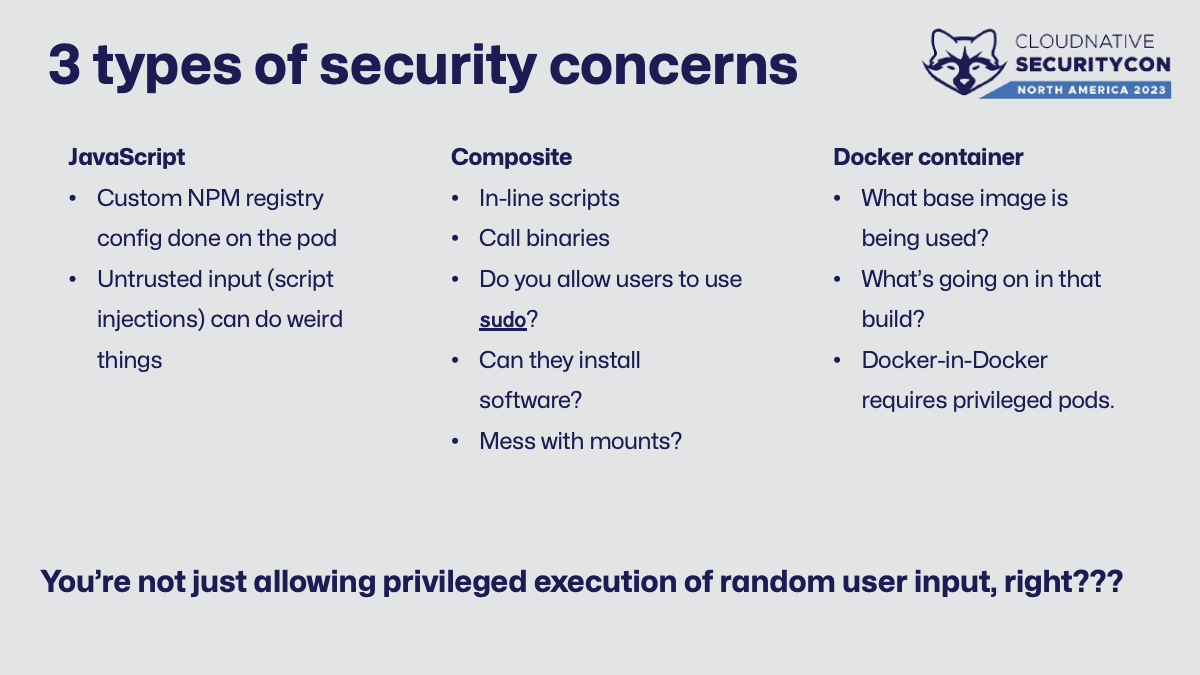

… because this is where we start with delineating security concerns.

There’s two points I’d like to highlight for JavaScript. First is that it (likely) relies on dependencies in NPM. This is (again, likely) covered by your company’s fabulous <everything repository> - so we need to make sure that repository is configured to be used by the runner image and, if applicable, every other container image in use by the pod. Because the runner pods are ephemeral, that is, they exist for the lifetime of one run of a task, we’re going to be using that repository quite a bit continually installing dependencies.

Next concern to note is the possibility of script injections from your users. Two things to consider here is the trustworthiness of the Action that’s in use (a straightforward problem totally out of scope today) and that the users can pass arbitrary inputs into it and inject their own silly or malicious input2. This is a decent way to try and escape your container or otherwise partake in security shenanigans.

That script injection concern is also relevant for composite Actions. They assemble other Actions, run scripts in arbitrary languages or binaries, etc. Adding in the more “VM-like” permissions of allowing users to alter their environment, perhaps granting privileged access, etc., and there’s a trust exercise I don’t want to join.

Lastly, Docker Actions run by building and running a container … in a container. Apart from your normal container security concerns around image provenance, what’s going on in that build, etc., Docker-in-Docker requires --privileged - more on that in a minute.

⚠️ You’re not just allowing the privileged execution of arbitrary user input in your Kubernetes cluster, right?! ⚠️

Cluster settings

The first thing to talk about with teams wanting to build their own in-house implementation of Actions on-premises with Kubernetes is to talk about how they’re planning on deploying it. For all the reasons outlined above, this is a phenomenally tricky workload to isolate. Is this cluster shared with other workloads such as applications, or other teams, or customers?

Zero trust is not a default setting in Kubernetes. It’s possible and it requires skilled work and upkeep to pull off. Namespaces do a fantastic job providing resource quotas, sharing secrets, setting policies, and more. The team running this will need to maintain and set up access control, admissions policies, ingress/egress, etc., that become tedious to manage at scale.

There are some projects that allow for another abstraction (usually called “tenant”) to template network/pod security policies, RBAC, quotas, etc., together. That makes this use case easier, but we’re still sharing a cluster. There’s also some promising work happening on Kubernetes-in-Kubernetes, but I’m not sure I’d go all-in on this for production workloads versus using other technologies built with “don’t trust your neighbors” in mind. I’d love to hear that I’m wrong here, though!

The opposite direction you could take from this concern is to have a ton of clusters, all isolated to their own unique teams. Cluster sprawl is also a problem - adding extra infrastructure to inventory, secure, and maintain becomes incrementally more expensive. There’s no single right path to finding this balance, as I only want you to think through the risks of multi-tenancy versus managing lots of single-tenant clusters.

When I was learning Kubernetes a few years ago, there was a moment in reviewing various security standards and thinking “well, duh, of course you shouldn’t ever run stuff as root”. Didn’t we solve this before containers with mandatory access control systems, like SELinux or AppArmor , for other processes in Linux?

It turns out that all the privileged pods are running various continuous integration systems in Kubernetes. Privileged pods effectively removes the fun process isolation that separates a container from just running a command as root on a local box. While I’m not going to tell you “thou shalt not use privileged pods” (you have compliance frameworks for that), it never seems like a risk that was deliberately chosen either. It doesn’t have to be this way!

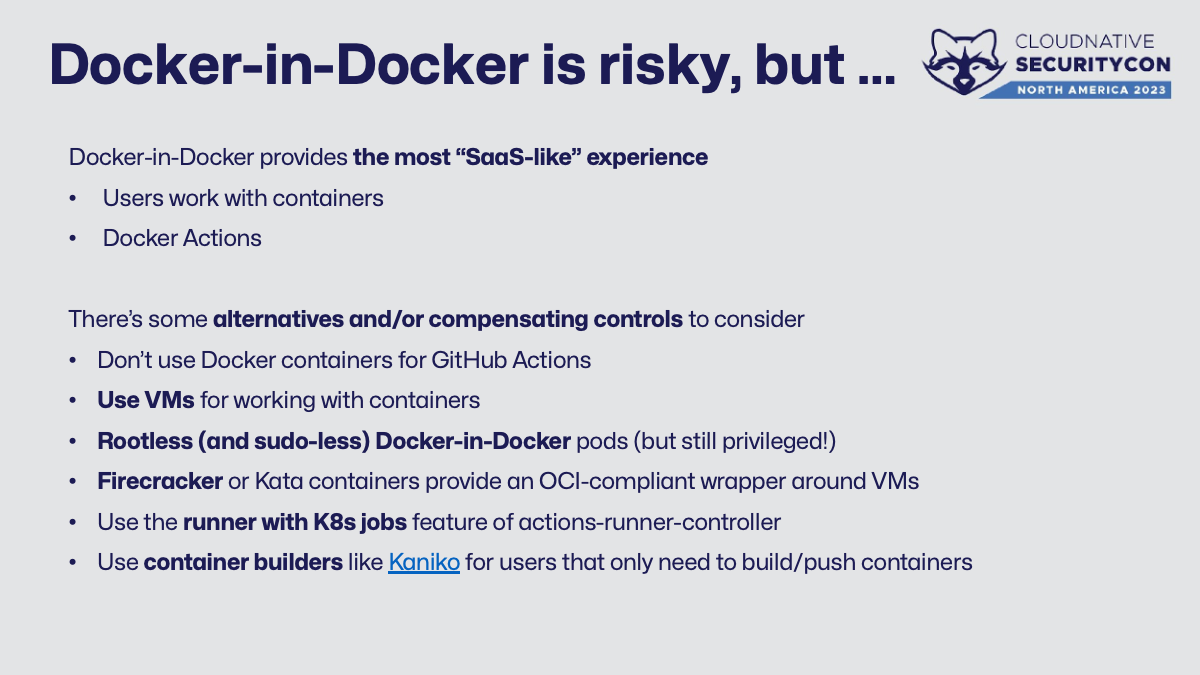

First, let’s talk Docker-in-Docker - that drives a lot of the usability versus security concerns of actions-runner-controller implementations. Users want this for two reasons - either building containers directly or through using Docker Actions. It’s simple, expedient, and risky to allow privileged pods. Harder and safer is to at least consider some ways to accomplish the same task without granting so much elevated access. Here’s a couple of alternatives and/or compensating controls to consider.

- Don’t use Docker containers for GitHub Actions (this is hard)

- Use VMs for working with containers (this is also hard)

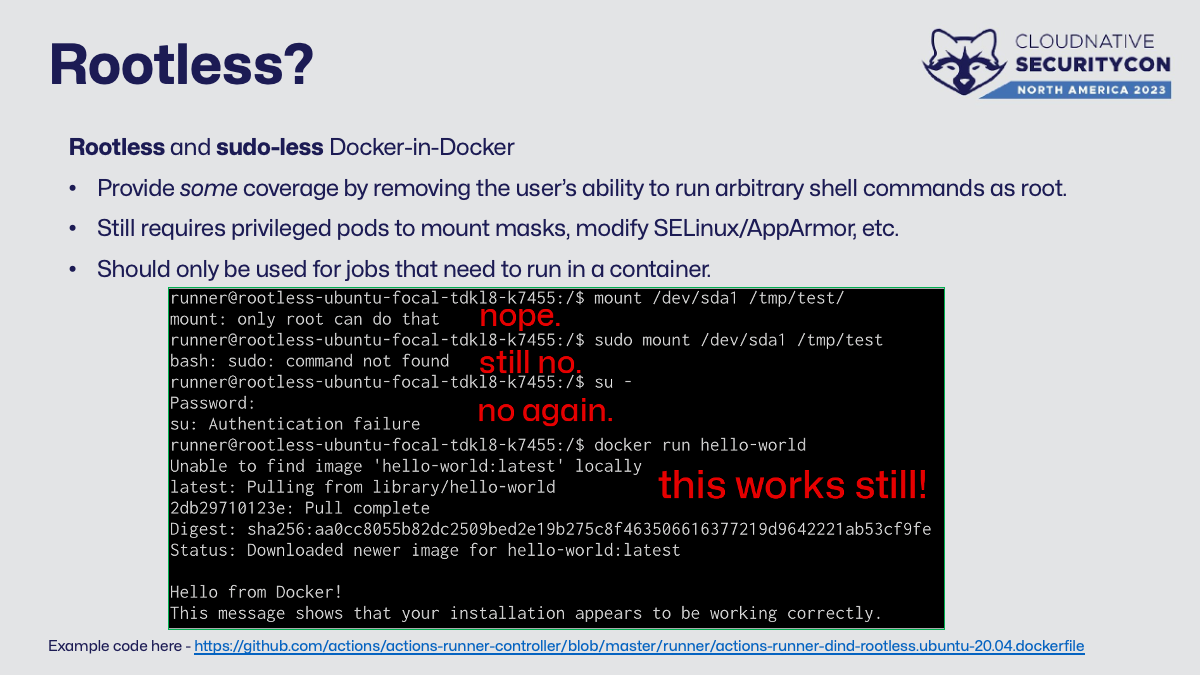

- Rootless (and sudo-less) Docker-in-Docker capable images (but still privileged!)

- Firecracker or Kata containers provide an OCI-compliant wrapper around VMs (here be death by a thousand cuts)

- Use the runner with K8s jobs feature of actions-runner-controller (worthwhile work to do rewriting a little bit to do this)

- Use container builders like Kaniko for users that only need to build/push containers (also worthwhile work)

“Just don’t use Docker containers for GitHub Actions” is a difficult policy to implement and maintain against user requests. Users generally don’t know which of the three ways of shipping an Action that was used. Without a clear explanation of why the request was denied, it seems arbitrary. Denial also doesn’t address the business need the user wanted to solve for. Grown-ups don’t ask for random things without a cause and I believe we all work with intelligent and kind adults.

We’re not at CloudNativeSecurityCon to talk about giving up and reverting to VMs - just know that it’s an option to not completely dismiss.

My contribution to this space is putting rootless (and sudo-less) Docker-in-Docker in a runner image. I believe in harm reduction when doing risky things and this is both acceptable and expedient for a lot of use cases. It’ll provide coverage against user silliness by removing as many common escape paths as possible while retaining functionality - namely removing sudo and running as a non-privileged user. There’s still a shell and common utilities that I’d consider risky in this context, like curl or wget. However, it makes a runner image that “just works” for both Docker Actions and building containers more generally.

There are significant tradeoffs made in this approach. First, it’s still privileged - it has all the same reasons for this that regular, rootful nested containerization does - mounting /proc, etc. Next, as there’s no elevated access inside the container and every effort is made to keep the bundled software to a minimum, any software or configuration changes will need to happen before runtime. This means users need to use this only for working with containers or rebuild the image on their own to include more software.

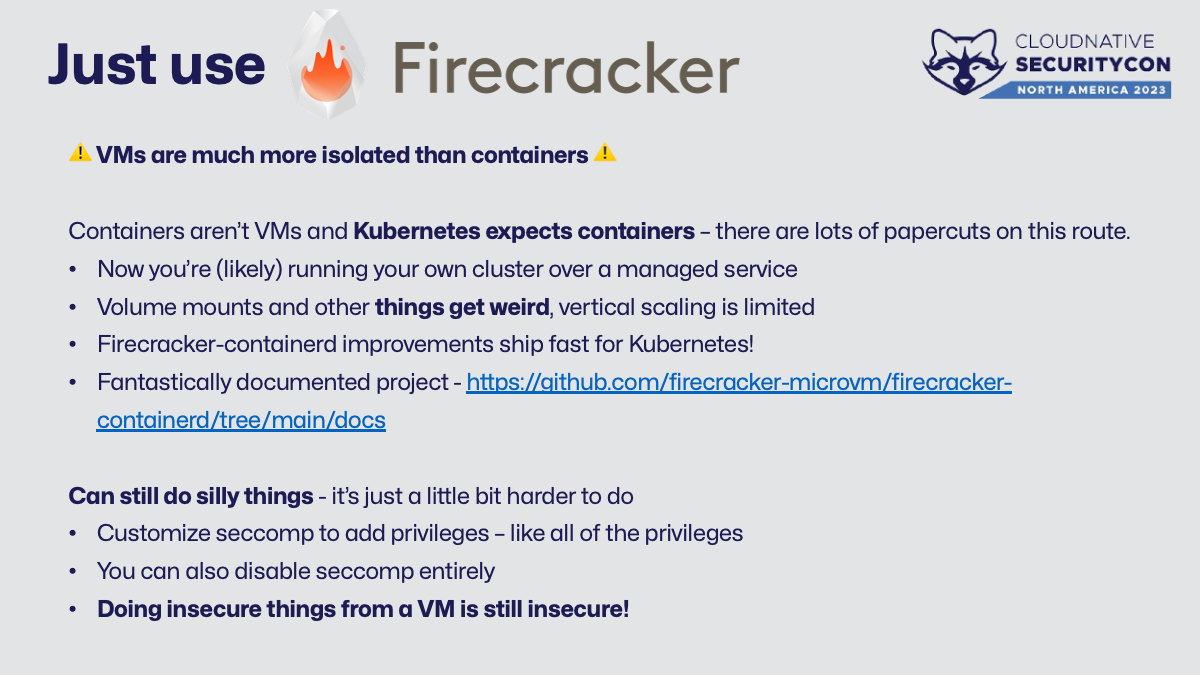

This is the point in that architecture discussion where someone in the room says “Just use Firecracker” or other “make Kubernetes orchestrate virtual machines” technology. It’s a solid idea. VMs are much more isolated from both each other and the host than containers are. Here’s where I’ve seen teams going down this route have a difficult and insecure time.

The first obstacle that I see is a bit industry-specific. There’s not many managed providers in this space overall – doubly so if you need a specific compliance certification (eg, FedRAMP). This means the team is likely running their own cluster on existing and authorized bare metal or existing VM infrastructure. This adds cost and complexity to the project. More importantly, it further increases how much of the platform security is on your team (again).

Next thing the team faces is all the paper-cuts encountered because Kubernetes expects to manage containers and ✨ containers aren’t VMs. ✨ The most common ways in addressing these paper-cuts undermine the very isolation that drives this overall architecture.

- Shared files bad, though, right? Well sure, but many workloads rely on secrets and configMaps and service account credentials and other such things to be shared. Volume mounts get weird and tedious and they’re used for basically everything.

- While

firecracker-containerdnow has a CNI compatible network plugin and you can have a couple containers in a “VM pod” (source ), not every “pod is a VM” technology has this. This complicates keeping isolation boundaries intact. - Insecure things on the admin side are still quite possible - modify or disable seccomp, drastically oversubscribe your physical resources, bridge networking between the “pod-VM” thing and the host, etc.

Lastly, doing insecure things from a VM is … 😮 … still insecure! Common security problems here include

- disabling SSL verification at build (my personal pet peeve)

- messing with software repositories or downloading non-managed dependencies on the VM

- piping random stuff to a privileged shell -

curl | sudo sh - publishing to an internal registry, writing to a shared mount, deploy to any specific environment, etc. from this super-secure-only-because-it’s-a-VM build system is not guaranteed to be as secure as planned

The GitHub issues of actions-runner-controller, firecracker-containerd, and other dependencies to pull this off have lots of asks to “help me accomplish this anti-pattern”. It’s not a bad idea at all, but lots of time, money, and smarts go into pulling it off.

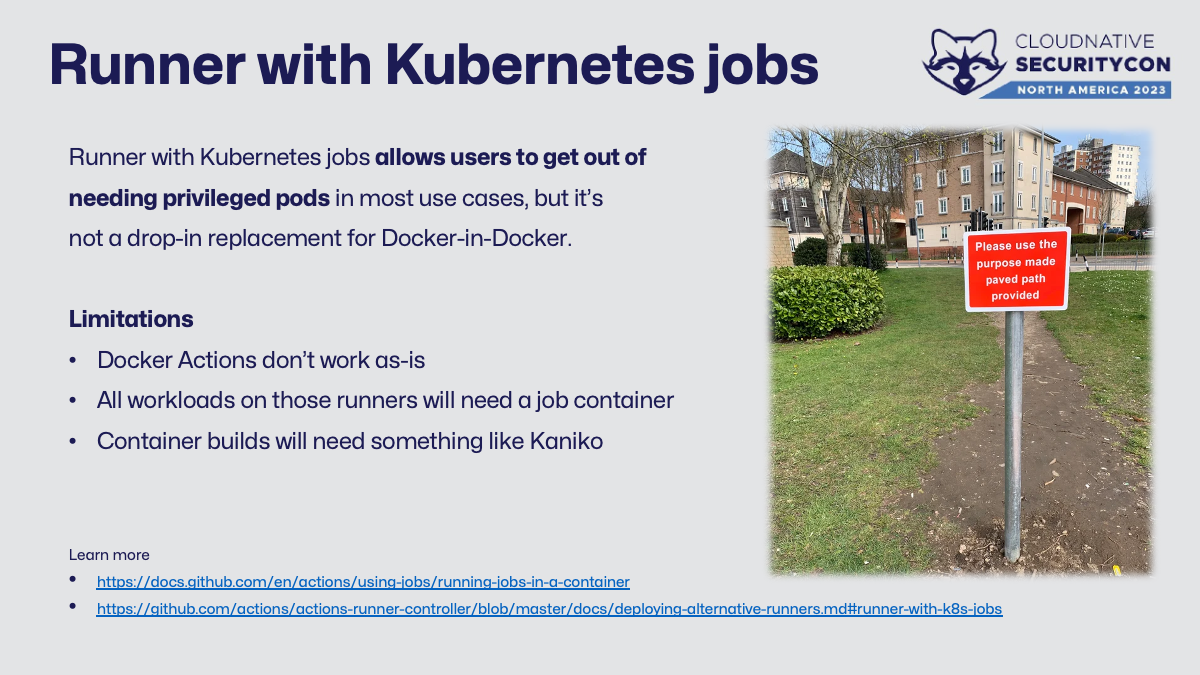

Just like in this picture, there’s a lovely paved path to not requiring Docker-in-Docker - runner with Kubernetes jobs! It’s a little longer up front to use it, but much safer (or less muddy, to stick with the picture analogy).

It uses some hooks (here ) and a service account to “un-nest” Docker-in-Docker to shove that into it’s own (non-privileged) pod running in the same namespace.

The big tradeoffs here go back to the two big reasons we see nested containers. Docker Actions don’t work as-is. To address this, build the container yourself and push it to your internal registry, then remap the inputs and outputs as an internal composite Action. For container builds, you’ll use a container builder like Kaniko or Buildah to build and publish.

In conclusion, there’s no single best path forward here, but lots of good guidelines. Avoid privileged pods as much as you can. It’s work, but worthwhile work, to rewrite some existing workflows to be container-friendly. The “paved path” here is to use the runner with Kubernetes jobs. If that’s not possible, segregate your work that requires privileged access to limit the amount of damage that can be done by a container escape. To help limit that, you can look to a rootless and sudo-less Docker-in-Docker runner or shift to using Kubernetes to orchestrate virtual machines.

The wide variety of possible needs means it’s hard to provide specific guidance apart from the fact that it can be hard to co-tenant diverse continuous integration jobs in Kubernetes - so let’s talk about how multi-tenancy works in actions-runner-controller!

Controller settings

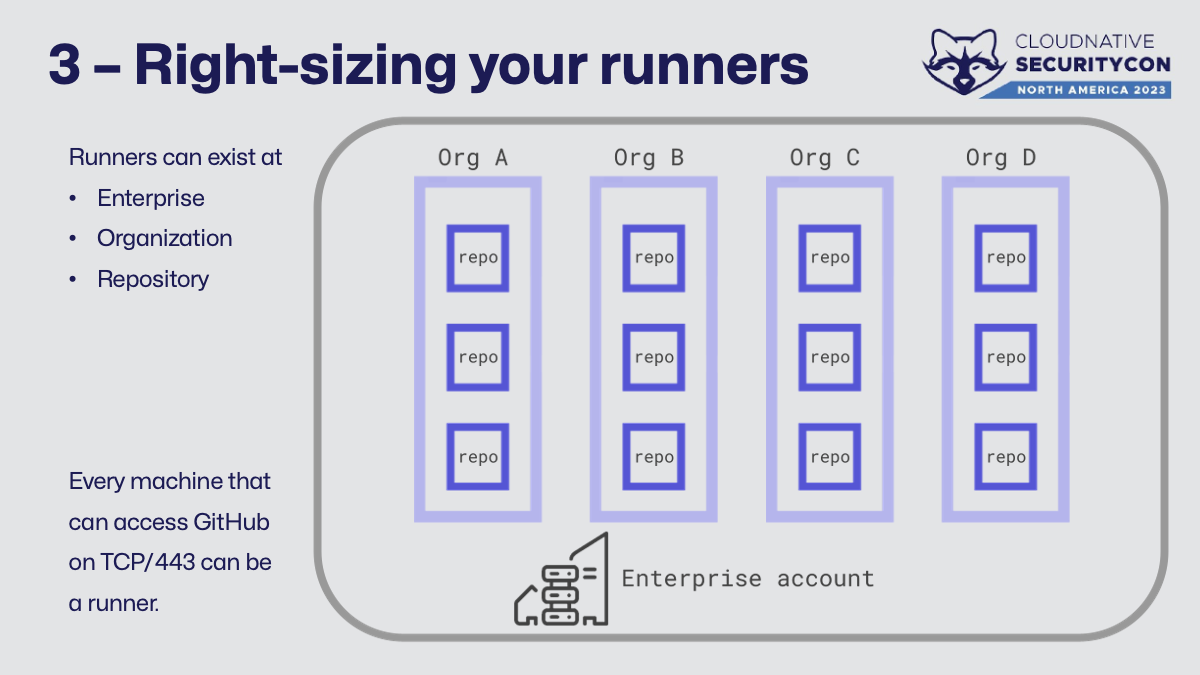

Within GitHub (cloud and server), every machine that can access GitHub on TCP/443 can be a runner. This gives administrators and developers a lot of flexibility in “right-sizing” the deployment that works safely for them. A runner can be attached at one of three levels:

- Repository runners can only be seen and used by that repo. The workflow files can target it (or not) as the repository admins see fit.

- Organization runners can be seen and used by anything in that org. What can or can’t use them is set by organization ownership.

- Enterprise runners can be seen and used by anything in the enterprise. Policies can be set both by org owners and enterprise admins – there’s a dual consent model for usage.

Security dictates the right group to place the right compute image at – broad where you can and narrowly scoped for everything else.

Apart from the risk of container escapes, how actions-runner-controller handles secrets at the moment is less than ideal. It’s also the only method available for it at the moment.

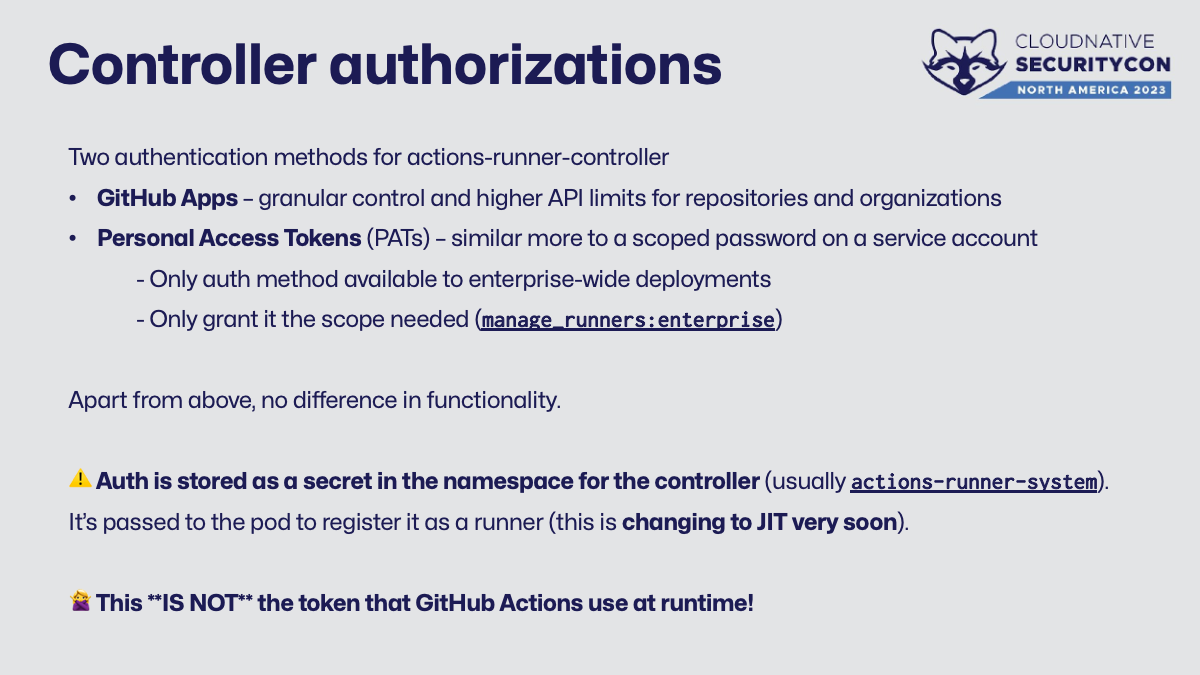

There are two authentication methods for actions-runner-controller, GitHub apps and personal access tokens (PATs) . A GitHub app allows for higher API limits and more granular permissions, but is only available at the repository and organization level. PATs are more similar to a scoped password on a service account. It’s the only method of authentication open at the enterprise-wide level, so please ensure to only grant it the minimum scope needed (manage_runners:enterprise) and don’t just “check all the boxes”. This scope is only available to enterprise admins, so it’s a big risk to give it more access than needed. Apart from what’s noted, there’s no difference in functionality for ARC.

The reason that giving the token too much permission is so risky is at the moment, this authentication is passed to the runner to join it to GitHub and is stored as a secret in the namespace of the controller.

Authentication is changing to just-in-time authentication soon (link ), but until we’re all there, this is something to be aware of.

Another important note, this authentication is NOT what GitHub Actions use at runtime. That automatic token used by a running job is unique to each time the job is run. It is granted permissions by the workflow file and the defaults are governed by repo/org policy. You can read more about that token in the docs .

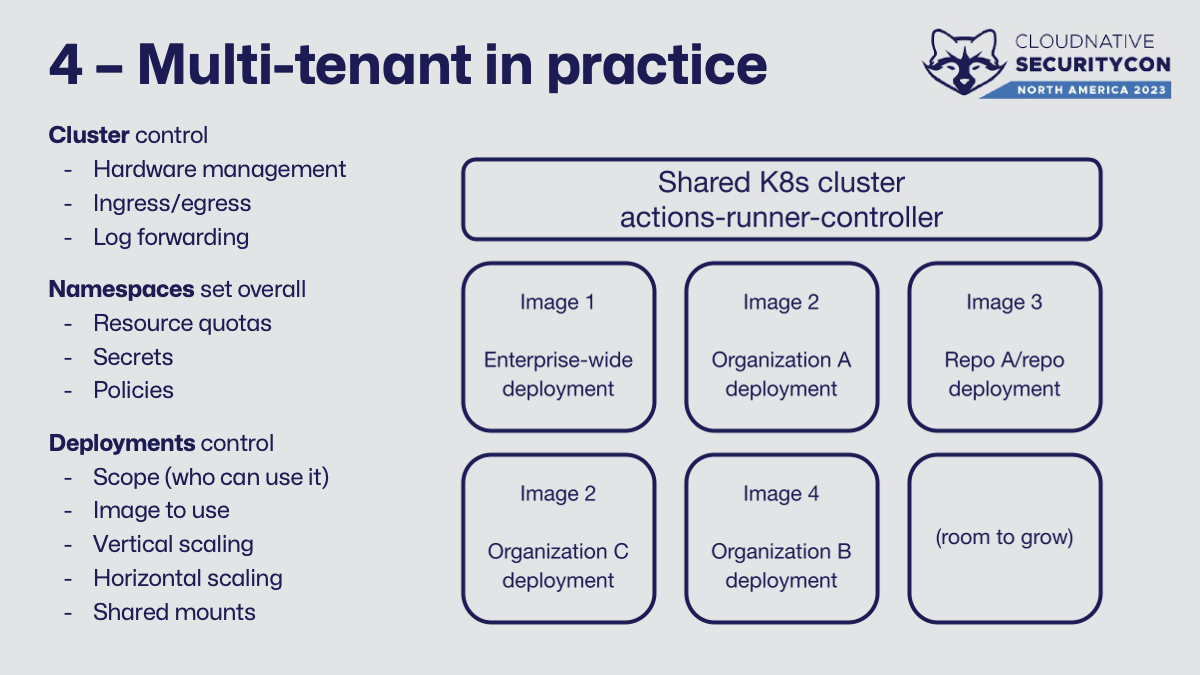

Here’s what multi-tenancy for actions-runner-controller looks like in practice. It’s designed for convenience more than security outright. This is still amazing in that by providing compute to teams, you can provide that insight and (some) governance to the supply chain of your end product (software). Going back to my bias we started with:

✨ Reducing user friction reduction improves security posture. ✨

The cluster provides hardware management, ingress/egress controls, log forwarding, other node security settings, perhaps a shared private registry, and other resources as needed. Namespaces provide resource quotas, secrets (not in lieu of an external secret manager), and network/pod admission policies. I tend to recommend one namespace for ARC per organization in GitHub as a starting point, as one namespace can hold multiple deployments, but this really depends on your company and the requested workloads more than anything else.

A deployment will control the scope (who can use it - repo/org/enterprise) and a lot more about that particular type of runner. Common settings here include which image to use and what, if any, shared mounts to set up. It also controls horizontal scaling (how many runners to have) and vertical scaling (resource requests and limits).

See how there’s no production workloads such as an application or other non-CI jobs here? That’s no accident. Even with all the guidelines and isolation, I have a hard time trying to save a few dollars (and a little incremental extra time) for another cluster so that we can have 💍 One Cluster To Rule Them All 💍

Pictured, a 100% factual photograph of an institutionally important and totally untouchable team being told they can’t have root access in production (real citation3)

Pictured, a 100% factual photograph of an institutionally important and totally untouchable team being told they can’t have root access in production (real citation3)

Sometimes, developer empowerment comes in the form of “no, and here’s how I’ll help you do this better” – a mentality shift for all teams involved.

Since so much depends on it, let’s talk about designing and building your runner image(s) as a secure part of your software supply chain.

Pod images

As we started with, most users build their own runner images. A typical image will usually be based off a broad OS tag, such as ubuntu:22.04 or ubi:8.7 . This is a derivation from best practice, where you base off a very specific tag. It ends up not being as much of a problem in this use case, though. The “base” software is updated for you beforehand, so you don’t bloat your image up with apt update and then trying to clean the cache to save some space during build for routine rebuilds. “Yum update”, et al, doesn’t usually break stuff (but you should have acceptance testing on new images anyways).

Next is user account set up, things like adding a user to run as, perhaps granting it additional groups (such as docker) or sudo privileges. Big red flag if there’s no user account setup – friends don’t let friends run as root.

Next is setup for the runner agent and any dependencies the users need. Sometimes, logging scripts (example ) or other scripts are copied in. Configuration files to use with your internal registries, etc., are also common.

Sounds a lot like a VM, doesn’t it? I’ve found it common for teams to start by “rebuilding” or making their current VM infrastructure in a container. I’m not convinced this is awful because they’re still gaining the hardware/cost efficiency benefits over VMs immediately. As teams have bandwidth to work down on vulnerabilities (that were likely there in the VMs anyways), it encourages removing things not needed – reducing attack surface and making more of a traditional “single purpose” container.

The patterns here are weird because the “single purpose” of this container is making increasingly “generic” other things – it’s pretty hard to fit it into the “discrete container does X and only X” pattern. Over time, I’ve found that teams move this way anyways.

Init scripts are a really good addition to containers for this use case. Yelp’s dumb-init is popular and has a good explanation as to why. UBI also publishes a base container with an init script (creatively called ubi-init for each UBI base image version). PID 1 is special. For Actions, if a container is executed, sending SIGTERM to docker run will kill docker but not the container. This use case tends to have longer running tasks that have multiple processes end up with a ton of zombies at PID 1.

Here’s some examples to get started. First, actions-runner-controller publishes three (all based on Ubuntu) to start.

- runner without docker - dockerfile

- runner with docker-in-docker - dockerfile

- runner with rootless and sudo-less docker-in-docker - dockerfile

There’s also a ton more alternative runners from the open source community here !

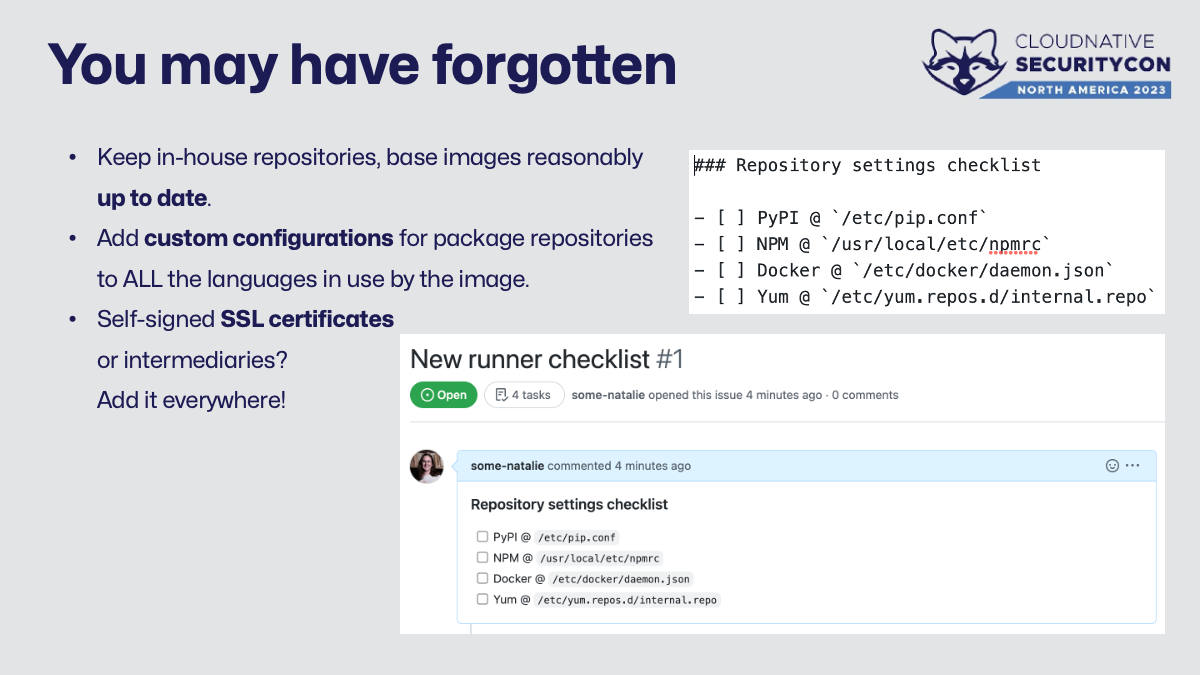

Common things that get overlooked with huge security consequences:

- Keeping the in-house repositories and base images reasonably up-to-date.

- Adding the custom configurations for package repositories to the image. I’m a fan of using markdown checklists in an issue or pull request template to ensure consistency here.

- Lastly, if your company is messing with TLS encryption at all, make sure the image is set to trust that literally everywhere. For every developer that notices your break/inspect SSL proxy, another 10 have just permanently disabled SSL verification to get their job done. The security consequences of this last way longer than any one project or contract with a cloud access security broker. Disabling SSL verification means your job will never fail because of it - even when it should!

Logging is another weird consideration in actions-runner-controller. There’s a couple places that emit logs and which you collect depends on what you really want to know.

The “easy button” is also probably the most important. GitHub has an audit log for things that were done - such as pull requests, git events, publishing packages or releases, etc. The exact contents and availability of the API depend on if you’re on the enterprise plan and/or what version of the self-hosted product in use, so check the docs for specifics.

Next is the console output from each Actions workflow. This is what users see within the GitHub web UI as a job runs. There’s an API to interact with this here .

Lastly, that logging script copied into the pod prints out a bunch of debug information to the console as it starts up and runs. It’s handy to view with kubectl logs for troubleshooting, but I wouldn’t consider it valuable. If you want to keep it, setting that up is on you.

Sharing mounts is risky - not horrifying, just more risk to consider. It’s commonly done for a few reasons:

- You can give I/O intensive builds super fast disks!

- Inner and outer Docker don’t share a build cache - so the inner Docker build-a-container job can’t leverage the cache on the node (outer Docker)

- Pulling dependencies on an ephemeral agent takes up a ton of bandwidth between the cluster and wherever that’s getting pulled from. Setting them up also takes time on each run. No one wants to wait on builds.

Rate limiting is expensive. I’ve (accidentally) taken down an entire large company’s ability to use Docker Hub - so for the rest of the day, hundreds of developers could not pull new images that didn’t exist locally. Hundreds of IT help desk requests resulted from this, as well as quite a large waste of money.

The problem with the “share big directory as mount” approach is the risk of unintended data persistence when privileged pods and arbitrary jobs writing to disks. When we’re constantly thinking through container escapes and user shenanigans, this one seems a bit more risky than having more images with larger in-image cache. Bandwidth internally and time to spin up new pods are cheap compared to external bandwidth or developer time.

The picture on this slide is from the 1794 patent to the cotton gin, widely credited for popularizing interchangeable parts. GitHub Actions is also super modular, so let’s build our own CI pipeline with our CI tool!

Roughly, a pipeline to manage the runner images usually contains the following steps:

- Build it – with what builds your containers, usually Docker or Buildah

- Scan it – container security (not VM/hardware) scans can fail the PR

- Create and upload an SBOM – record what’s in the thing

- Sign it – record that this image really is what we say it is

- Tag it – things get opinionated here

- Test it – find what’s broken before users

- Ship it! – the squirrel has spoken, ship it!

Swap in what’s already in place for container scanning, testing, deployment, etc. This allows maximum reuse and minimal tools to manage.

I want to talk a bit about building and tagging, but as an aside on testing – having an additional “test-things” type namespace for this is great. GitHub Actions makes for a robust testing platform for these images – things like software availability, scaling works as expected, configurations and connectivity work as planned, etc. – but those are all custom-configured for your unique environment.

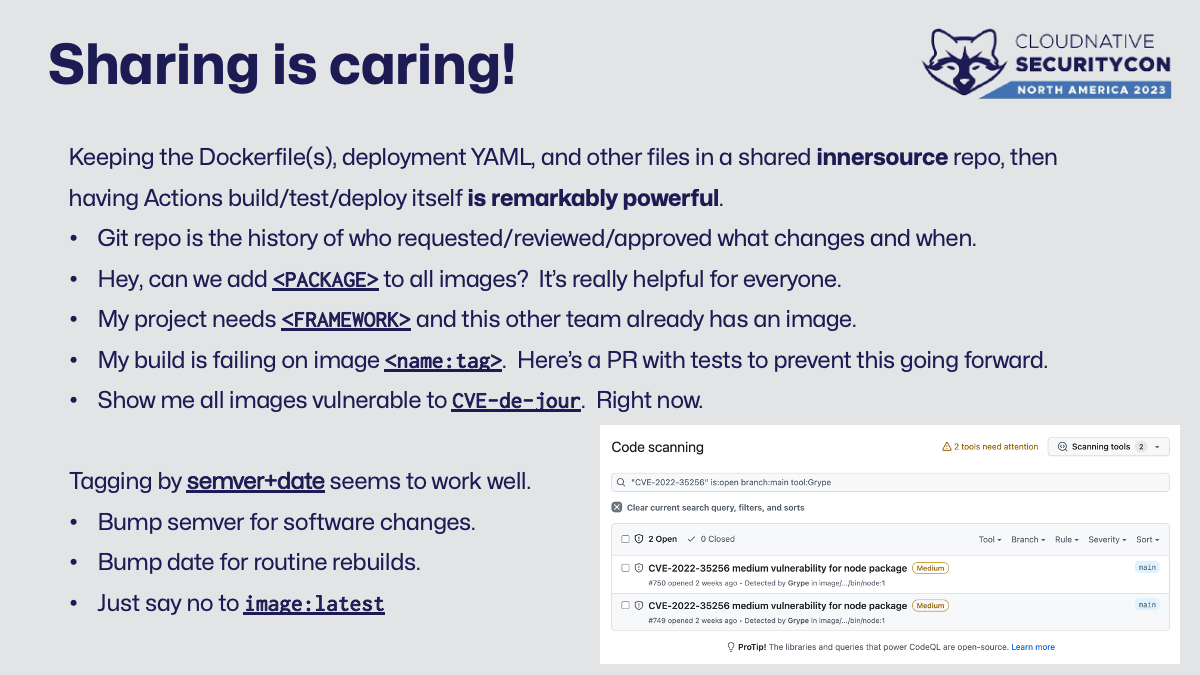

Building containers in and of itself isn’t particularly fascinating - the change that comes from sharing this process is! It’s likely no one here’s first foray into gitops, but when combined with sharing openly (internally) you get transparent security, easy audits, and fast empowerment.

In my time going down this path and in helping others do the same, here’s a handful of situations we faced:

- Can we add

packageto all images? It’s helpful for everyone and I really need it to dothing. - My project needs

frameworkand another team in a business unit I’d never talk to already has it. Let’s reuse it. - My build is failing on

runner-image:tag- here’s a PR with the fix and some tests to prevent it going forward. - 🔥 Show me all images vulnerable to

scary CVE in the news. NOW! 🔥

In keeping everyone’s images in one internally open repository, the overhead on security operations is drastically lowered. The tradeoff in this active participation by every stakeholder is more overall chatter - but meeting needs and making sure everyone feels heard is truly worthwhile. When the next scary CVE hits, it’s a easy search to figure out which images are affected - not a multi-week 24/7 fire drill.

Tagging images is a unique exception to common practice. Several teams I’ve worked with independently came up with some combination of semantic version and build date/time. The time portion bumps automatically on builds or routine rebuilds, but semver only changes when software changes.

No matter what you choose, remember there is no hell quite like trying to fill out an incident report against latest. The who/what/when is impossible to prove for what’s going on where. Does your pod get pulled every time or only if not present? Did you scale to 0 or were there “older latest” pods hanging out that might get work? 😱 😭

Conclusions

❓ Why does it take a month to go from user request to deployed image for adding a tiny well-known utility to an image that is only used by one team?

❓ Why are there significant numbers of people who respond to that question with “I wish it only took a month!” for this?

In my experience, everyone involved in running a CI system – from security, to operations, to developers, and everyone in between – walks a bit of an adversarial tightrope time to time. It’s simultaneously one of the most critical business systems with the most people interested in it and most frequently changed. I have seen more grown adults argue over this than anything else, more than text editor flamewars or favorite Linux distribution. We don’t have to balance plates on sticks or “just say no” to everything. It doesn’t have to be this way.

I’m fond of pushing this process through a pull request reviewed by users, admins, and security. It’s trivial to add required reviewers to touch specific files - here’s how . Everyone is a stakeholder which means that everyone also has a service level objective to meet on addressing requests.

The bigger risk to the very foundation of your software supply chain isn’t that user asking to include a small utility package or to have access to a privileged pod. It’s that user getting frustrated waiting – process-heavy ITSM tickets to nowhere or waiting yet another month for the next change management window – so they configure their own build server or disable SSL certificate verification or their own “bootlegged” copy of that utility that’ll never get updated, to just get things done and move on with their life. Reducing friction makes everyone happier and safer.

❤️ Take care of your team and they’ll take care of you. ❤️

Footnotes

-

GitHub publishes a guide on security of Actions. The section on self-hosted runners (link ) is very much worth reading several times over. ↩

-

The same document has a section on untrusted input for Actions here . ↩

-

Balthasar Permoser (German, 1651–1732). Marsyas, ca. 1680–85. Marble on a black marble socle inlaid with light marble panels. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund and Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 2002 (2002.468). link ↩