Shrinking container images (part 4) - trying out some slimmer apps

Some containers are big and with a good enough reason to be big. Reliably reducing their size isn’t difficult or complicated, but it is work. Let’s see if we can find a shortcut.

Having been handed complex codebases and told to “do something” is a sadly recurring theme in my professional life. I’m a big fan of shortcuts. This seems like a good problem to find an easier path. 🦥

There are multiple tools that promise to “slim and secure” or “harden” your containers. I’ve spent the past few weeks digging into a couple, both open-source projects and commercial offerings. Let’s see if they can help us out.

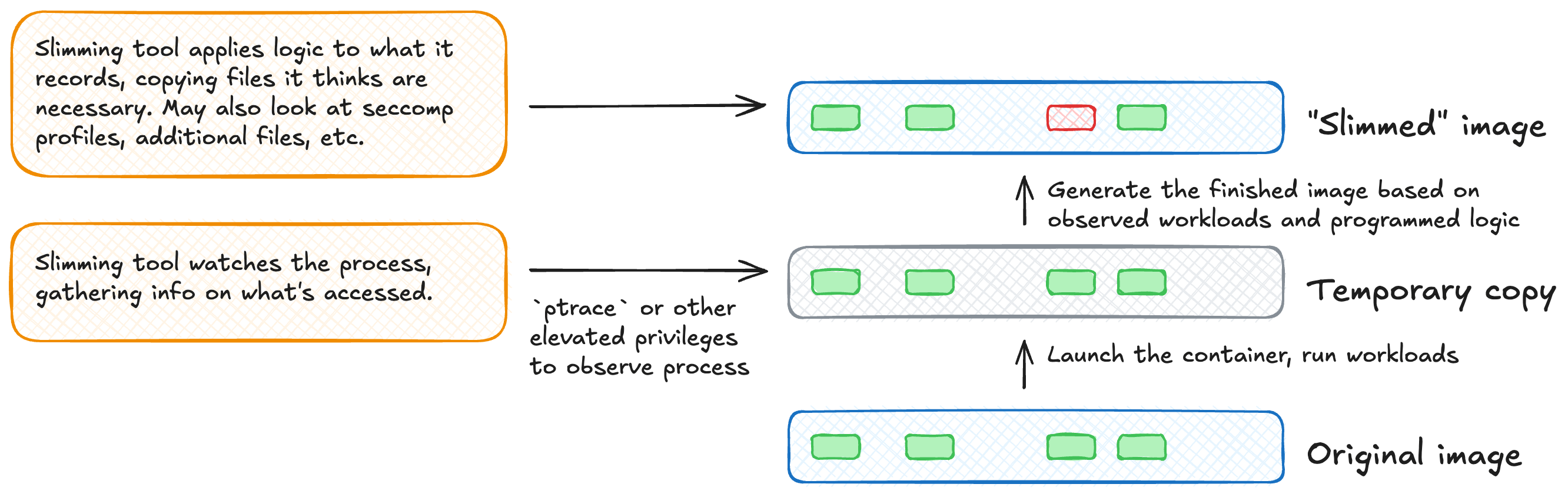

How it works

At a high level, container slimmers work by watching your existing container run. It then adds the files it sees accessed or changed into a blank image it creates. This blank image is usually called a “stub” and will become the “slimmed” edition of your container. Some projects include some base files in that stub, others use scratch. The exact mechanism for watching that existing process varies by the project you’re using. It typically involves asking for elevated permissions on the host (usually CAP_SYS_PTRACE (man page )) which allows the slimmer access to the container’s memory.1

Example - a simple Python app

Let’s learn how these tools work by looking at a simple python app that I’ve built and deployed to a container. It’s a single page Flask app that solves fizzbuzz , a trivial programming exercise. There’s a spot for user input, it’ll return simple output, and all of the files are here .

Before going through our “slimmers”, the image is 156 MB in size and has at least one CVE in every severity level. Most CVEs affect the operating system components that are included in the base python:3.10-slim image. Notably, the version of Flask that it uses has a high severity CVE in it (GHSA , NVD ) that can be easily resolved by moving to a newer version.

| CVE severity | Before slimming | After slimming |

|---|---|---|

| critical | 1 | 0 |

| high | 4 | 0 to 1 |

| medium | 16 | 0 |

| low | 5 | 0 to 2 |

| negligible | 60 | 0 |

| unknown | 4 | 0 |

Depending on the tool, the image size at the end was between 20-30 MB. The number of CVEs was reduced substantially, with some tools leaving enough for the Flask CVE, but … that’s only because every tool deleted or overwrote all of the files that tell a scanner what’s in the image. The CVEs that definitely would still exist in the smaller image, such as the one in Flask or the ones in the version of Python running, just weren’t reported.

Some scanners helpfully log, but not fail, when they can’t find the files they expect to see. Unless you know what to look for in the output of a scanner, you’ll just see a low number in some dashboard. False negatives become a much larger problem.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

# Some example logs from Grype

[0003] WARN Unable to determine the OS distribution. This may result in missing vulnerabilities. You may specify a distro using: --distro <distro>:<version>

[0011] WARN cannot parse field from path: "/usr/local/lib/python3.12/site-packages/zipp-3.21.0.dist-info/METADATA" from li

[0011] WARN cannot parse field from path: "/usr/lib/python3/dist-packages/iotop-0.6.egg-info/PKG-INFO" from line: "File re

# Some example logs from Trivy

DEBUG OS is not detected and vulnerabilities in OS packages are not detected.

INFO Detected OS: unknown

INFO Number of PL dependency files: 0

How do you know what you know?

The inspiration for this post came from conversations with customers on findings in various scanning tools and what that really means. How container scanners work and what they’re looking for is fundamentally broken by the way that these “hardeners” or “slimmers” work. Scanners want to see the files that tell them what’s in the image. If you delete or modify those files, you’re not making your image more secure - you’re making it harder to understand but smaller too.

One of my amazing colleagues, Jason, built a maximum cve container image that’s only 2.0 MB in size. It packs an astonishing 687,955 CVEs in it as of writing this piece.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

~ ᐅ docker inspect -f "{{ .Size }}" ghcr.io/chainguard-dev/maxcve/maxcve:latest | numfmt --to=si

2.0M

~ ᐅ grype ghcr.io/chainguard-dev/maxcve/maxcve:latest

✔ Vulnerability DB [updated]

✔ Parsed image sha256:a2608ac82878e37acd255126678d47f44546

✔ Cataloged contents 0ff9859d5a577fdfa7e2da0c3f3d4abccef88c30d70

├── ✔ Packages [44,346 packages]

├── ✔ File digests [1 files]

├── ✔ File metadata [1 locations]

└── ✔ Executables [0 executables]

✔ Scanned for vulnerabilities [687955 vulnerability matches]

├── by severity: 39134 critical, 141107 high, 144887 medium, 13058 low, 0 neg

└── by status: 671280 fixed, 16675 not-fixed, 0 ignored

However, the only things in it are the os-release file (telling the scanner “I’m an APK distro”) and the apk database (listing what’s installed in the image).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

.

├── etc/

│ └── os-release

└── lib/

└── apk/

└── db/

└── installed

There are no files or executables to be vulnerable in the image. This same concept works for virtual machines and other infrastructure scanners too. The image does exactly nothing and can’t be compromised because it doesn’t do anything. It’s a fantastic example of scanners only being as good as the data they can see.2

Example - continuous integration workers

Using that, let’s look at our more complex example of a CI worker. After running them through a slimmer, each was reduced to anywhere between 10% and 80% of the original size. All reported a significant reduction in the number of CVEs.

However, once I tried to use those images as runners, my life became a nightmare.3 They would all join GitHub and accept jobs, but one would fail to run any job once it was dispatched. Another would only run some Javascript jobs. Some pre-made Actions worked, others didn’t - and that list changed several times because the dependencies in those Actions changes too. There were dependencies that weren’t captured for various shell utilities (such as ls or curl), or each time one changed, the runner would fail to run a job until it got rebuilt/rehardened/redeployed.

(╯°□°)╯︵ ┻━┻

The lack of a complete set of pre-determined inputs/outputs is what makes this situation so terrible. Other non-deterministic uses of containers would likely be equally fragile. These cases would include developer workstations (devcontainers), other types of CI workers, jobs needing to do something on user input, or anything with a frequently-changing dependency tree.

Size and security aren’t tightly coupled

We started seeing this trend in our simpler examples in tidying our builds or squashing each image. Size and number of CVEs in an image aren’t as tightly related as it seems.

| image | image size | cve count |

|---|---|---|

| ubuntu-jammy (runner) | 1.15 GB | 180 |

| ubuntu-numbat (runner) | 1.20 GB | 97 |

| wolfi (runner) | 1.15 GB | 1 |

| ubi8 (runner) | 938 MB | 559 |

| ubi9 (runner) | 920 MB | 551 |

| maxcve (literally does nothing) | 2 MB | 687,955 (all false positives) |

| fizzbuzz (flask app) | 156 MB | 90 |

| fizzbuzz-slim (flask app) | 20 MB | 1 (unknown false negatives) |

Size and number of findings in an image aren’t entirely unrelated either, though.

- ✅ Fewer packages/executables/dependencies mean fewer CVEs.

- ✖️ A smaller image will always have fewer CVEs.

- ✖️ A scanner is a reliable source of truth on a container without package information.

- ✅ Keeping dependencies up to date will reduce the number of CVEs in an image.

I have a bias. I want to know the risk I’m responsible for. It is much more important to understand your risk than it is to report a lower risk than is true. Or … you know … just keep that résumé polished for the next gig.

In practice

From the teams that have invested significant time trying this, they’ve found it tricky and labor-intensive to implement at scale for a few reasons. For the regulated industries that follow NIST 800-53 or derivatives (FISMA, CMMC, FedRAMP, etc.), there’s some additional considerations:

- The end “hardened image” is only as robust as your staging or testing coverage, leading to flaky performance for complex apps.

- Missing files can make it hard to debug or log errors.

- It removes the package manager’s ability to verify software authenticity by removing trusted signing keys, a violation of SI-7 (Software, Firmware, and Information Integrity) .

- Legally questionable to redistribute slimmed images if it doesn’t include all the correct open-source licenses in the finished copy, as the GPL and many other licenses require.

- Not helpful for languages or tools that provide better ways to do this (static-linked builds, anything ending in

FROM scratch) - Seems to void the SLA guarantee on some commercial software, as Red Hat calls out .

Perhaps most importantly, it removes your ability to know what’s actually running in your systems. The files for dpkg, apt, yum, rpm, pip, and so much more are needed to understand what’s present, detect differences between what’s expected and running, and so much more. Without having this information, it’s difficult to prove compliance to CM-8 (System Component Inventory) .

The files that tell you what’s in the image were deleted or modified from the original in the output of every tool. If disk space is that important, sure, design some POA&Ms and mitigating controls around these problems. Using these tools for application security makes it as truthful as Enron’s accounting.4

paper shredders for evidence or

paper shredders for evidence or rm -rf evidence … same results

Where it works

When your system is simple, you know what’s in it, and you’re just trying to get a bit more space, these tools can be helpful. Sometimes you need to write a container image to a Zip drive and just need a bit more space to get under that 100MB limit. 🫠

If you’re trying to go down this path, here’s some hard-earned advice:

- Have phenomenally comprehensive test coverage that would touch every possible file and do every possible thing in your system

- Use that test coverage to make sure you’re not missing anything during the “hardening” process

- Rebuild, update, and reharden often to actually address the CVEs you may not see in a report

- Meet your security controls elsewhere in the software development lifecycle

- Scan your images and understand your CVE posture before feeding it into the tool to make it smaller

- Know what’s in your system and keep an eye out for things that would become insecure after slimming such as authentication or authorization configurations or allowing what would have been a protected file to be written by anyone

… which … sounds like a lot more work than I want to do for some disk space to be uncomfortably honest.

Slimmers can do a bit of what you want … with what you should already know about your systems … less well than if you’d done it right to begin with.

Disclosure

I work at Chainguard as a solutions engineer at the time of writing this. All opinions are my own.

Footnotes

-

Please trust your container’s software and the entire supply chain that went into it before running anything that grants

CAP_SYS_PTRACEto a container. It’s such a powerful capability to modify the host’s memory. Most of the time I demo a container escape live, this is my path out to explore, exfiltrate info, or gain persistence. ↩ -

If you want to go super deep into this topic of malicious scanner compliance, I highly recommend watching this talk at Kubecon Europe 2023 . It’s well worth the time to watch several times. ↩

-

There is no hell quite like debugging GitHub Actions. ↩

-

Enron was a company that took a “the books are whatever I want them to be” approach to accounting and vaporized billions of dollars in the meantime. It was brought to my attention during editing that a rather large portion of folks will not get this reference. Wikipedia has a good explainer, plus more links to learn more, if you’re interested. ↩