Static analysis scans of a container's filesystem

User - “We need a SAST scan of our container images.”

Me - “You’re using two container scanners already. Do you mean static analysis of the source code before you put it into a container?”

User - “But it’s not on the list of scanners for source code. We need to run the whole container through the static analysis tool too.”

And here we are - a questionable idea of running a static analysis (SAST) tool against the filesystem of a container image. It’s not going to get you much for actionable data, but it will check a box for you.

Why it’s questionable

A container scanner and a static analysis tool are different tools looking for different problems in an application. They complement each other.

A container scanning tool (eg, Grype or Trivy) works by looking at the container’s file system, parsing the contents and dependencies for Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVEs). These, fundamentally, are looking at the security of other people’s code - the dependencies brought in to build an application on top of. The output is a list of known issues in “pre-built” code.

A static analysis tool (eg, Semgrep, CodeQL, etc.) looks at the application code for security vulnerabilities, code quality, and other issues. These tools analyze your code for issues undefined by a CVE. The output of these is a list of higher-level problems that may or may not be wrong with your code, such as unsafe input handling or memory allocation, that could lead to a security problem.

How to do it anyways

Different tools to find different types of problems that produce different reports … but sometimes you need to check a box for compliance. Let’s get it done.

Setup

Start by dumping the contents of a container image to the filesystem. We’ll use a tool within Google’s container registry called crane to export the contents of a container image to a tarball, then expanded into a directory.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

# make and change into a temporary directory

mkdir -p /tmp/crane && cd /tmp/crane

# pull and extract the container image's contents

crane export cgr.dev/chainguard/python:latest python.tar

tar xf python.tar

rm python.tar

From here, you can scan these files with whatever static analysis tool you’d like. For this example, we’ll use Semgrep open source to output a file to use in reporting or ingesting into other tools. This should work with other static analysis tools and platforms just as well.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

# install it (homebrew on macOS, follow your directions elsewhere)

brew install semgrep

# move into the directory with container files

cd /tmp/crane

# output json file

semgrep scan -j 1 --json-output=semgrep.json

# output sarif file

semgrep scan -j 1 --sarif-output=semgrep.sarif

Looking at the results

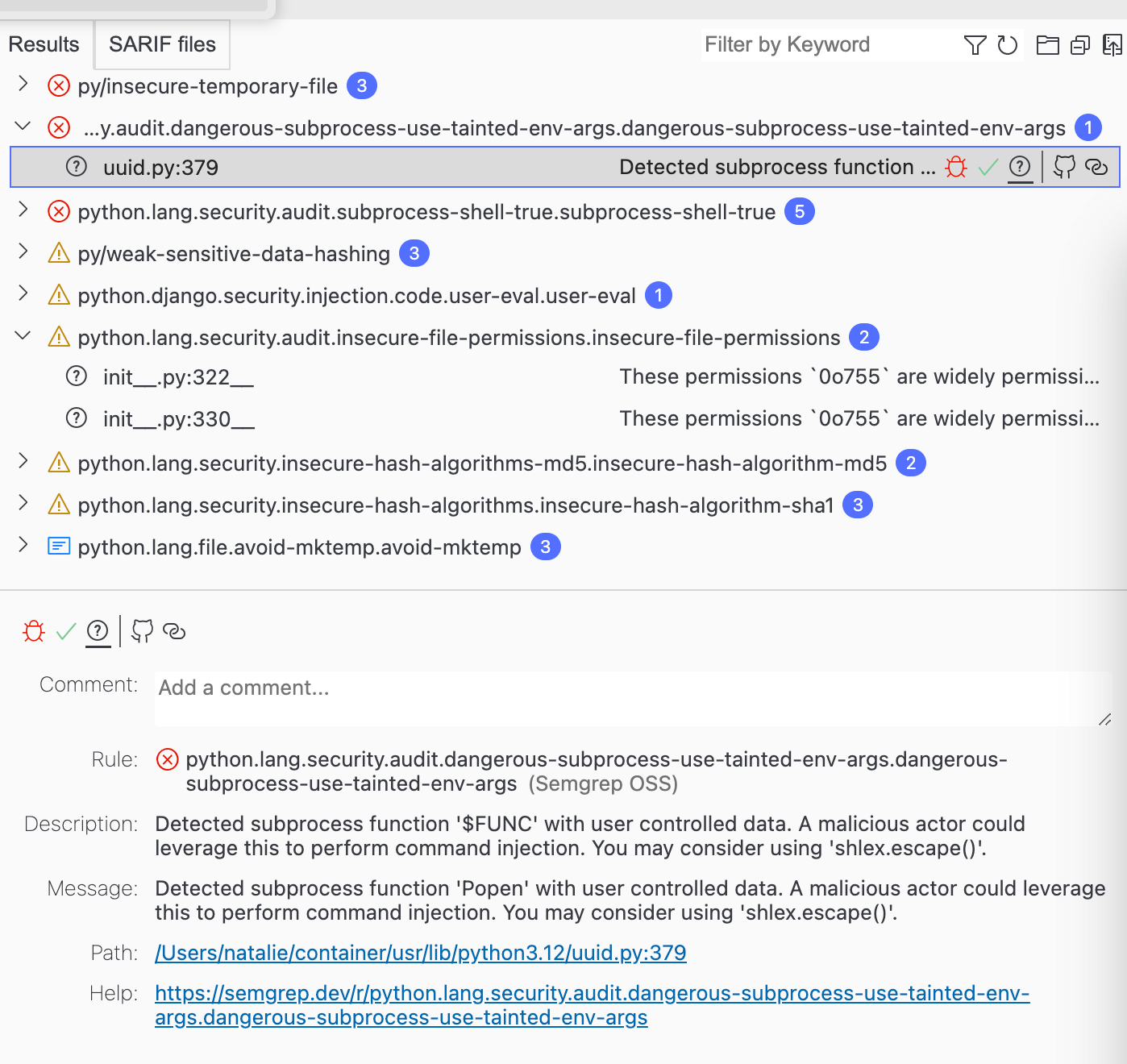

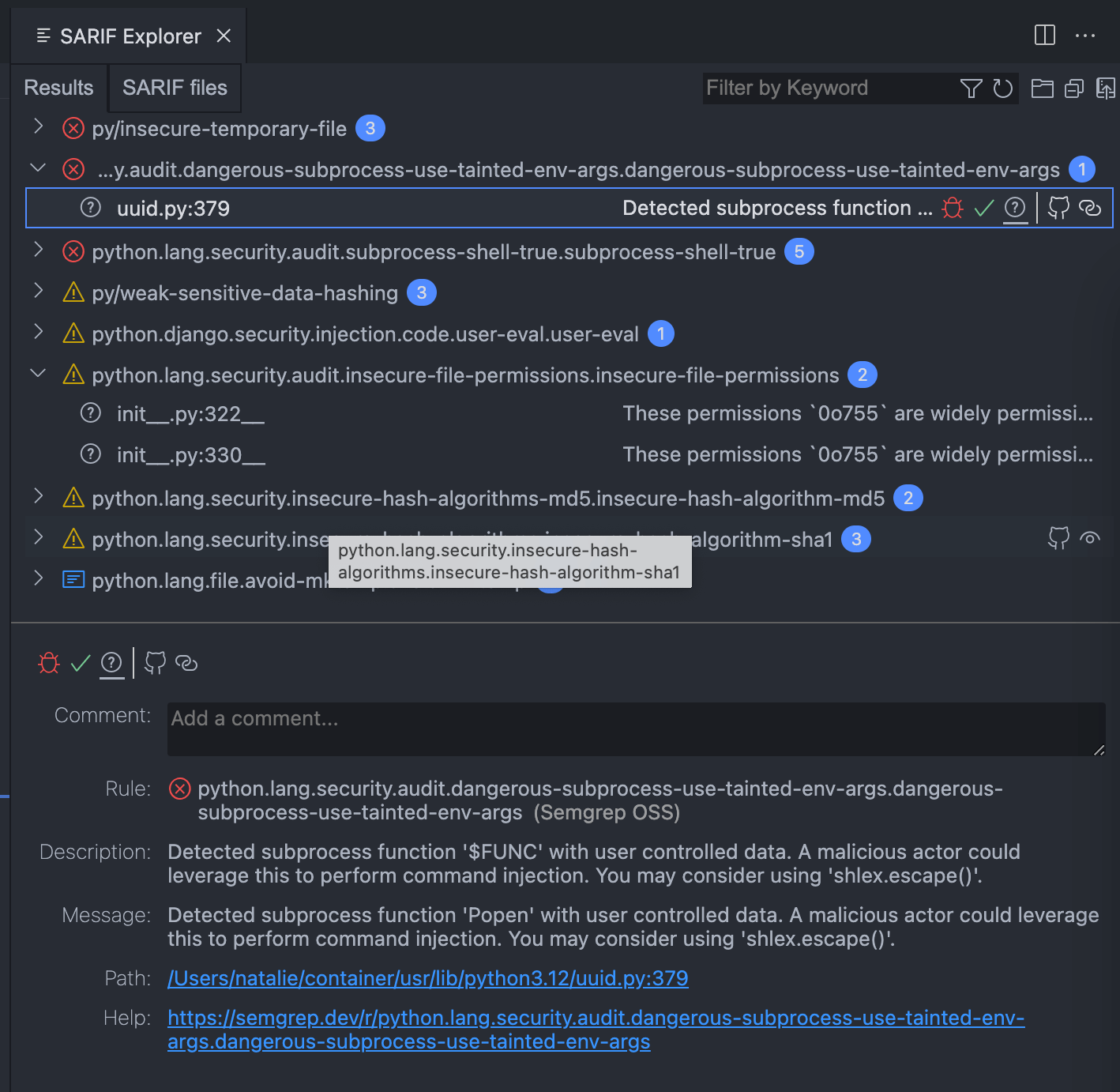

pretty boring findings that require a lot of work to explain

pretty boring findings that require a lot of work to explain

The findings aren’t terribly interesting in this case. Python is an exceptionally well-supporting and maintained project. Much of what’s here falls into a few categories:

- There’s an insecure file permission on

__init__.pyfiles. It can be, but doesn’t have to be, executable. The SAST tooling will complain about this no matter what, without much room for nuance. - There’s a finding about using environment arguments in a subprocess. Since this is what’s actually defining the

subprocessmodule, it’s likely how it reads environment variables - if I had to guess. Certainty may require a lot more work, here. Is that work worth it? is not an easy question to answer. - The last finding that stands out is support for hashing algorithms that aren’t strong but would be a breaking change to remove. Yeah, these shouldn’t be used. It can also be tricky or complicated to remove them from some projects too and sometimes these hashes aren’t necessarily used for something that needs to be secure.

A simpler path

Depending on how the application is built, this is at best difficult to do while there’s an equally effective and easier path to the same security data. When appropriate, it’s simpler to use static analysis before building the container. When it isn’t, numerous alerts that aren’t particularly meaningful require intricate discussion about each one - crowding out the findings that can be addressed by the team with those that may be better suited by choosing a better base image for your container.

Overall, this is likely to cause more paperwork than it saves. It follows the letter of what’s asked even if it’s not the spirit of the question. Sometimes that’s exactly what’s needed. 🤷🏻♀️

Disclosure

I work at Chainguard as a solutions engineer at the time of writing this. All opinions are my own.