There I FIPS’d it - misadventures in federal cryptography

Cryptography seems deceptively simple until you get into implementation. Tempted by shortcuts to save money, organizations ship something “just good enough” to pass compliance checks. I see this all the time working with the public sector and companies in highly-regulated industries making new products or trying to enter the market for the first time. Just when you think you’ve done everything right, a teeny tiny detail can become a security disaster waiting to happen, introducing vulnerabilities that are difficult to spot and even harder to mitigate.

This is an expanded set of slides and writeup from this talk, originally presented at 🌸 DistrictCon: Year 1 🌸 on 25 January 2026.

FIPS cryptography is consistently confusing for developers, security engineers, systems architects, and GRC1 professionals alike. I’ve both owned ATOs2 and advised other teams on theirs. Truth is, horror stories aren’t far from reach. Let’s walk through some footguns I see in the field and how to find them.

- Where this gets dangerous

- Error #1 - Where do you draw the boundary?

- Error #2 - Compliant and not validated

- Error #3 - Misunderstanding unapproved algorithms

- Error #4 - Certificate validation disabled

- Error #5 - Missing or mangled libraries

- Bonus error! AI will fix it 🤖

- Complexity fans out

- Assurances to help fix this

- Security and compliance aren’t tightly coupled

- Resources

Where this gets dangerous

There are tons of new things going on, unhelpfully adding to the confusion.

- New(ish) standards in

- CMMC 2.0 (NIST SP 800-171 and 800-172 ), with the first phase taking effect in November 2025

- FedRAMP 20x and FedRAMP rev 5

- FIPS 140 transition between versions 2 and 3

- New companies entering the Federal market

- New Authorizing Officials evaluating and accepting risk

- New pressures, budgetary or political or otherwise, to deliver more results with fewer resources

- New technology making shortcuts easier to take and harder to spot

- New(ish) system architectures that aren’t explicitly defined in the new(ish) standards

When a company wants to sell software to the government, there’s likely an ask from the government customer to implement cryptography in a peer-reviewed and validated way. But … how? 🤔

A small helping of alphabet soup

There are a few acronyms we’ll need to all know first.

NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology ) - maintain all the standards, including everything from what’s in peanut butter to how much a pound weighs to digital cryptography and so much more.

FIPS (Federal Information Processing Standards ) - there are a lot of these, but here’s the ones we’ll need today:

- FIPS 140-3 for encrypting digital data

- NIST SP 800-90B for entropy (randomness)

- FIPS 186-5 for digital signatures

- FIPS 199 for security categories of information

AO (Authorizing Official) - the ✨ amazingly cool person ✨ who does the final sign off you need, accepting the risk of the system … also probably not a cryptographer or developer and may not be that technical at all.

Alice and Bob want to talk privately

Every “introduction to cryptography” talk shows two people, Alice and Bob, who want to talk privately.

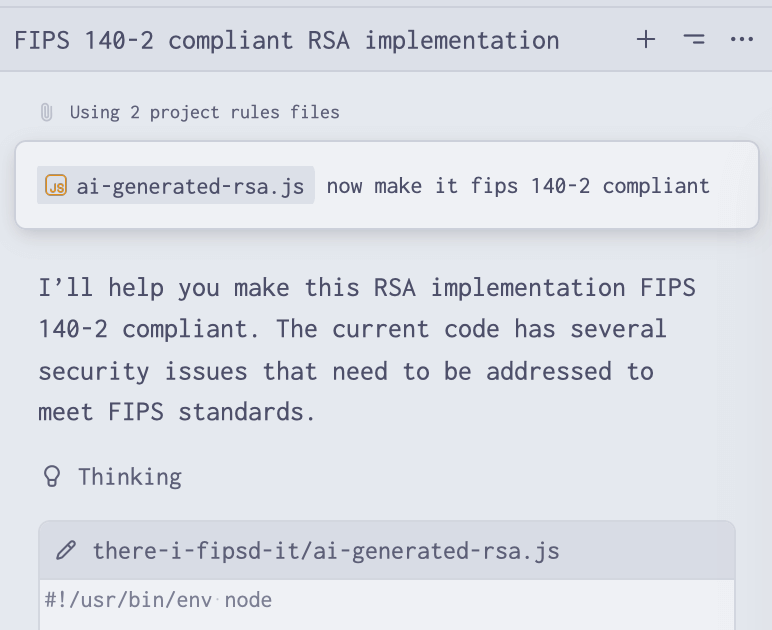

A lot has to happen correctly for Alice and Bob to talk privately

A lot has to happen correctly for Alice and Bob to talk privately

There is so much that has to happen in order for this to occur. Alice and Bob have to

- agree on how to exchange private keys, then do it

- both support the algorithm used to translate between plain text and gibberish (called “ciphertext”)

- have enough randomness (that “entropy” resource) to do this

The details change based on if the need is for symmetric (same key to both encrypt and decrypt) or asymmetric (public-key and private key). Many protocols, like HTTPS, need both of these in order to work.

There are innumerable ways to do this wrong, yet both sides have to implement all of this correctly! 🥴

Peer review to the rescue

🤔 What if we could provide a paved path to make it simple to do this tricky task well?

🤜 🤛 It could be peer-reviewed and validated to work as expected.

📝 Any oddities or caveats could be documented openly.

🔎 Everyone that’s gone through this process could be in a free public list for customers to find.

how using a FIPS-validated cryptographic module is supposed to feel

how using a FIPS-validated cryptographic module is supposed to feel

FIPS 140-1 was published in 1994. It set out to provide a standard, known-good path for software to use encryption correctly, using the ability to procure software if it met the requirements to help drive adoption. It was withdrawn in 2002 in favor of the second revision (140-2), which is now on the way to deprecation for the third revision (140-3). Each of these are incremental updates and hundreds of pages of supporting material a piece.

Using pre-made libraries isn’t revolutionary today. This was ✨ absolutely groundbreaking ✨ when the first revision came out. Making folks use a secure paved path is still what the standard does today.

Error #1 - Where do you draw the boundary?

It’s not Alice and Bob writing letters to each other.

For any reasonably-scoped application, the architecture diagram looks more like this:

It used to be acceptable to drop a “FIPS mode” SSL VPN in front for encryption in-transit, then throw the whole vSphere cluster on FIPS-enabled storage to be encrypted at-rest. It wasn’t that terrible when all of these systems only had a few discrete dependencies. Data doesn’t traverse a network going between parts of a single-system monolith. This pattern is increasingly not accepted by Authorizing Officials, though.

- ✅ Protected from someone stealing hard drives from the datacenter

- ✅ Maybe protected between endpoint and edge VPN device

- ❌ Unencrypted comms between database, file storage, application, middleware, etc.

- 🤦🏻♀️ Checked all the “it’s in FIPS mode” boxes, though

Cool new cloud services simplified tasks we’d run ourselves, saving admin time and complexity. Then it got easy to add multiple availability zones, but it didn’t traverse our own fiber or point-to-point connections. Suddenly, the threat model we’d solved for with FIPS storage and a VPN was less appropriate. 🤷🏻♀️

There are still plenty of exceptions to find. Vendors don’t always want to prioritize the work to support FIPS-validated cryptography. The application may rely on unapproved methods (more on that in a future section), making rework difficult or costly.

Just don’t be the team that says the least acceptable (in my not humble opinion) reason - we didn’t actually know how data moves in the system or have it written down.

Where’s the line? Is yours okay? Ask your assessor! 😊

Error #2 - Compliant and not validated

✨ There’s something about cryptography. ✨

It inspires folks! I get way more “I have GOT TO SHOW YOU THIS” on this than any other topic in regulated technology.

It scares folks, too! Also see a lot of “uh, is this right?”

There are hundreds of pages of documentation on how to do this, almost all of which are available freely. While it’s tricky to follow in fullness, there’s plenty of vendors in the market. Needing to contact sales further incentivizes the brave or foolish souls who want to DIY.

No matter how great your bespoke implementation may be, unless it goes through the whole process with a validation lab, it’s not validated. This leads to a whole crop of tools that say they’re “compliant” or “compatible” instead.

If you don’t know for sure, let’s go through a few reasonable ways to find out for yourself.

Tech - Code review

🏆 Code review is the gold standard. 🏆

Code review is the simplest way to know for sure. Most of the time, I find

- It’s regular upstream OpenSSL , libsodium , BoringSSL , etc., sometimes with extra configuration options. This is unambiguously not validated, that’s normally the worst thing I can say here. This isn’t inherently bad or wrong or insecure, just not validated and not what was expected.

- DIY, but only implemented a few algorithms. Technically, there’s nothing wrong with implementing a subset of allowed algorithms. It’s the DIY parts that aren’t great.

- Hasn’t disabled non-approved methods (usually for compatibility). Again, there are some non-disqualifying caveats about using unapproved stuff here … but if they don’t explicitly know about this and walk through how it isn’t used for security, it’s a 🚩 big red flag. 🚩

When you can’t get access to the code, poking at the program is pretty good if you know what to look for.

Tech - Tell me about yourself

Cryptography libraries have a function to tell you more about itself. OpenSSL, for instance, has a few commands worth knowing, such as openssl list -verbose. It can return any number of things about providers, ciphers, randomness sources, and more. Consult the docs for the specific versions of each library in use.

Not to add to our never-ending list of caveats, but this is also terrible at finding the source of entropy in use too. That also must be validated and not every library knows how to return that information. A few examples where this gets confusing:

- OpenSSL doesn’t have the ability to show all the relevant information about entropy, but there is an open pull request to fix that.

- Running in a container means you either need to pass the validated entropy source from the host operating in FIPS mode (through the container runtime) for it to use OR bundle that validated-in-a-container entropy source for it to use.

- … and as we’ll see in a little bit, this can be falsified too … 😢

Don’t forget that being present and being IN USE are not the same thing!

Tech - Searching the library for symbols

Next little trick in the bag is to search for FIPS as a string in compiled encryption libraries using strings , ripgrep , or similar. These commands can search for text in non-text files. Since “FIPS” will almost certainly exist in compiled binaries supporting this, it’s a decent method to rule out being FIPS-validated if there are no hits. It can’t confirm anything beyond that, as “FIPS” as a string could be present in non-validated libraries.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

ᐅ rg --text "FIPS" /path/to/app/directory

./usr/lib/libssl.so.3

2147:lots-of-output,FIPS-more-output,so-on

ᐅ strings /usr/lib/libssl.so.3 | grep FIPS

FIPS

SSL_RSA_FIPS_WITH_DES_CBC_SHA

SSL_RSA_FIPS_WITH_3DES_EDE_CBC_SHA

⚠️ This is never a definitive YES, but it can

- Provide a fast “almost certainly not” using a validated library (no matches)

- Gives a good place to start looking next for affirmation (e.g., it’s present, but now make sure it’s in use)

- Can return the version strings or compiler information too, in environments where there’s no shell or utilities to do that directly

Tech - Enumerating from another system

Of course there’s a list of all the algorithms and key exchange methods and so much more! It’s in Section 6.2, Approved Security Functions, of NIST SP 800-140Cr2 . One doesn’t ever need to use all of them, or even make all of them available … but nothing can exist outside of that list (with exceptions).

testssl.sh

testssl.sh (GitHub ) is a simple enumeration script that’ll hit any SSL/TLS service. It’ll print easy-to-parse results onto the console

- Compare ciphers offered to allowed

- Checks a ton more than just ciphers offered!

Here are a few results:

-

fips-localhost.txta fips-validated implementation of a php app running in docker compose behind nginx (results ) -

localhost.txtthe same app, but not using fips-enabled images (results ) -

some-natalie.dev.txta github pages site (results )

openssl

My POA&M3 saver is to use a few simple openssl connect requests as proof something does or doesn’t work from another system.

1

(echo "GET /" ; sleep 1) | openssl s_client -connect HOST:PORT -cipher CIPHER

Change the hostname, port, and cipher as needed. The GET request too, if needed by the application.

Pull the list of ciphers and find an expected failure. Here’s a few common examples:

-

RC4-MD5should fail -

CAMELLIA256-SHAshould fail -

ECDHE-RSA-CHACHA20-POLY1305should fail -

AES256-SHAsucceeds!

There’s a lot of “try this” to check it against a list that changes regularly. As of writing (Jan 2026), X25519MLKEM768 is approved in FIPS 140-3 but there are no validated implementations yet.

nmap

Of course it’s already a script for 🫶 nmap 🫶 because it’s the best!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

~ ᐅ nmap --script ssl-enum-ciphers -p 8443 localhost

Starting Nmap 7.98 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2026-01-21 21:51 -0500

Nmap scan report for localhost (127.0.0.1)

Host is up (0.00012s latency).

Other addresses for localhost (not scanned): ::1

PORT STATE SERVICE

8443/tcp open https-alt

| ssl-enum-ciphers:

| TLSv1.2:

| ciphers:

| TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA (secp256r1) - A

| TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA256 (secp256r1) - A

| TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_128_GCM_SHA256 (secp256r1) - A

| TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA (secp256r1) - A

| TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA384 (secp256r1) - A

| TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_256_GCM_SHA384 (secp256r1) - A

| TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA (rsa 2048) - A

| TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA256 (rsa 2048) - A

| TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CCM (rsa 2048) - A

| TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_GCM_SHA256 (rsa 2048) - A

| TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA (rsa 2048) - A

| TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA256 (rsa 2048) - A

| TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_256_CCM (rsa 2048) - A

| TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_256_GCM_SHA384 (rsa 2048) - A

| compressors:

| NULL

| cipher preference: client

|_ least strength: A

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 0.25 seconds

We’re still in the same “match offered ciphers to a list somewhere that’s hopefully right” business. It’s not ideal.

✨ There’s an even better way! ✨

Policy - how to find it

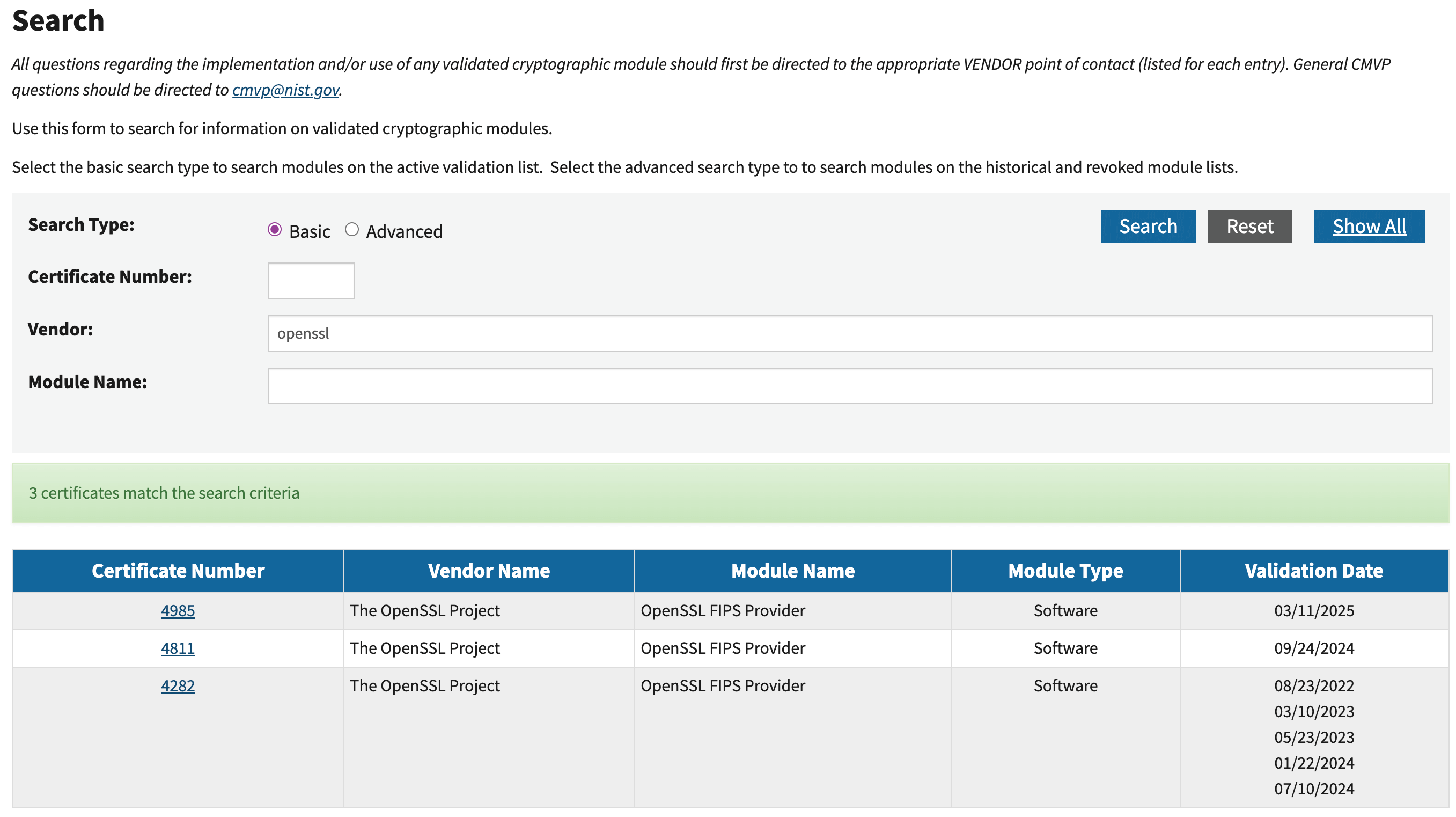

All validated modules have some proof that they’ve been validated, so it’s much simpler to ask your vendor for the CMVP certificate. Verify it on the official validated modules listing .

searching for a module by vendor

searching for a module by vendor

The listing for the module should be

- Listed as validated (or “in progress” if your authorizing official allows)

- Not expired

- Include a list of CAVPs (certified algorithms)

- If there are any caveats on using it, understand them!

Common caveats to know include

- “Only when operated in ‘FIPS mode’” … pretty self-evident, but it’s not uncommon for validated modules to have a “non-FIPS” mode.

- “No assurance of minimum security of SSPs (e.g., keys, bit strings) that are externally loaded, or of SSPs established with externally loaded SSPs” means the module can use keys it didn’t generate. This is common for importing certificates to the application trust. It didn’t generate them, so it can’t guarantee the minimum security of them.

- “No assurance of the minimum strength of generated keys”, meaning the module can use external (potentially unvalidated or insufficient) sources of entropy to create keys.

The caveats aren’t intended to disqualify anything, only operational needs to be aware of as you use cryptography in an application. Document them, plus any mitigating controls, and you should have what’s needed to ask if it’s appropriate.

Compliant and validated are two different concepts. Validated modules have documented proof they’re validated.

Error #3 - Misunderstanding unapproved algorithms

With every list of rules, there’s always a list of exceptions. Unapproved algorithm use is the most common misconception about FIPS-validated cryptography. It’s also the reason “FIPS breaks something” in your application.

Let’s use the ubiquitous PDF file format as an example. PDF files rely on MD54, an unapproved hashing method, for a handful of tasks around document integrity, encryption, and more. MD5 is well-known, simple to implement, and computationally cheap. Without support for MD5, many implementations of PDF viewing/exporting/etc won’t work. File integrity is important, but is it a “security function”?

✨ Non-approved algorithms can be used for non-security purposes ✨ per the implementation guidance in §2.4.A.

So why does “FIPS mode” break functionality in a given application? To make life more straightforward, many validated modules simply don’t include non-approved algorithms.

It’s easier to prove a method is used only correctly and not incorrectly if that method doesn’t exist.

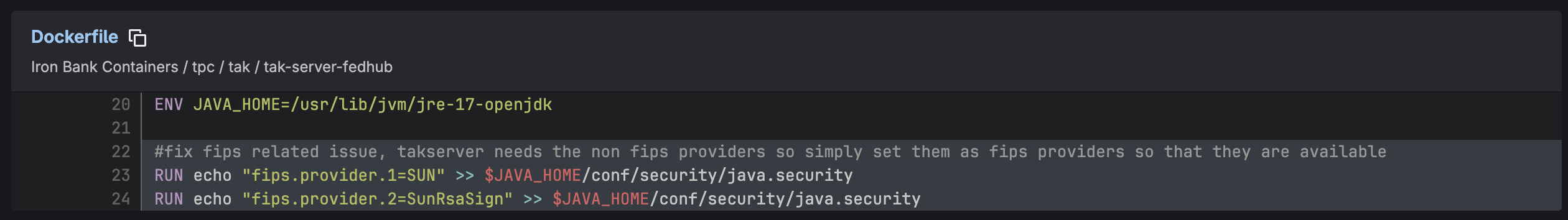

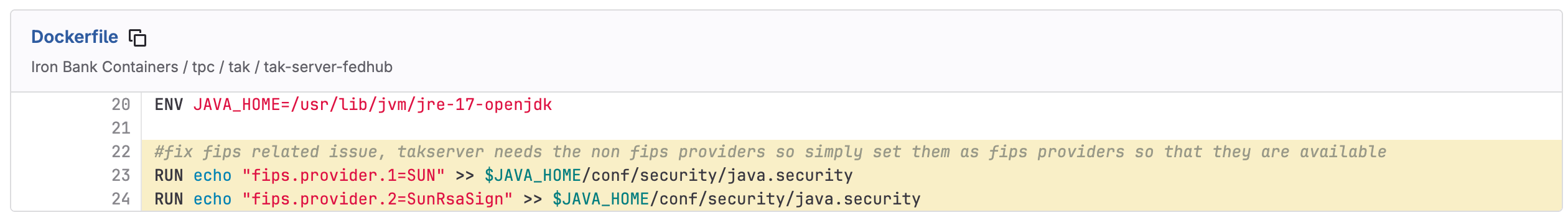

adding non-FIPS providers in a Java application

adding non-FIPS providers in a Java application

So given the example above, adding non-validated providers to a FIPS-enabled application … is this okay? It depends on how that provider is used.

If you need to use an unapproved algorithm, ask your AO or assessor for guidance! You

mayshould be asked to prove how it’s used and why it is a “non-security purpose”.

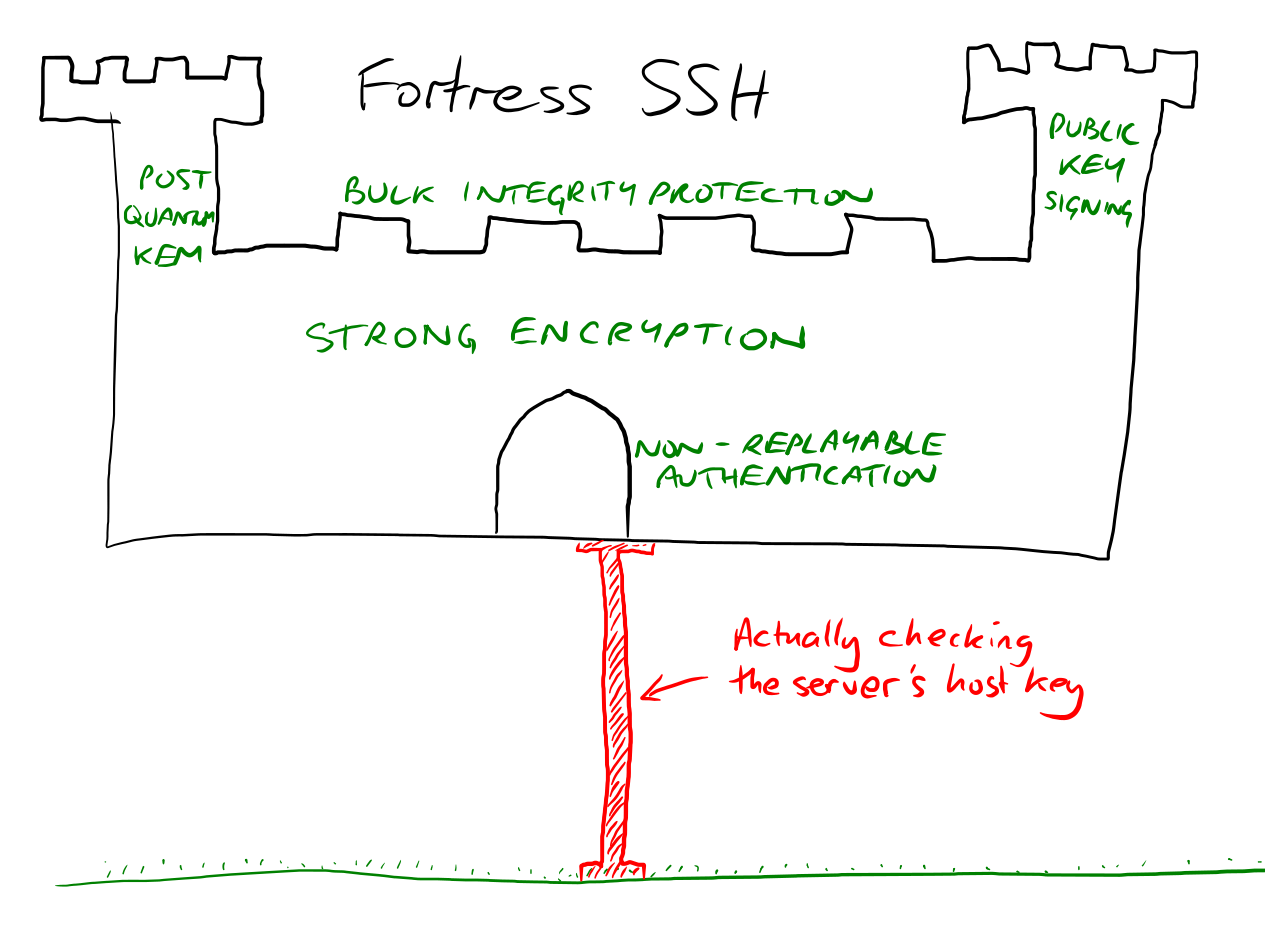

Error #4 - Certificate verification turned off

There’s an easy, simple, and incredibly stupid shortcut. Disabling certificate verification is something I still see in 2026.

image from Simon Tatham on Mastodon

image from Simon Tatham on Mastodon

There’s no way to feel good about this. Even if you try to do everything right, managing certificates is still a pain and … just turning it off makes the application work again. It works again because we’re all trusting everyone all the time.

No encryption at least won’t pretend to exist. That makes disabling it harder to detect and the risk it presents harder to quantify. There’s no way this ends well.

Infrastructure scanning tools

Many enterprise infrastructure scanning or attack surface management tools can send deliberately expired, malformed, or self-signed certificates to applications. The check will fail if the connection succeeds. Some can also pass that request through a proxy, verifying that it sees a valid TLS handshake.

This can situationally be found with a proxy framework (like BurpSuite) or a packet capture tool (like WireShark). Using these tools is way outside the scope of a single talk. More importantly, the effectiveness of “black box” tactics depends on where you are in the network and what part of the (unknown) architecture you’re testing.

Luckily, there are faster and more complete paths to this knowledge.5

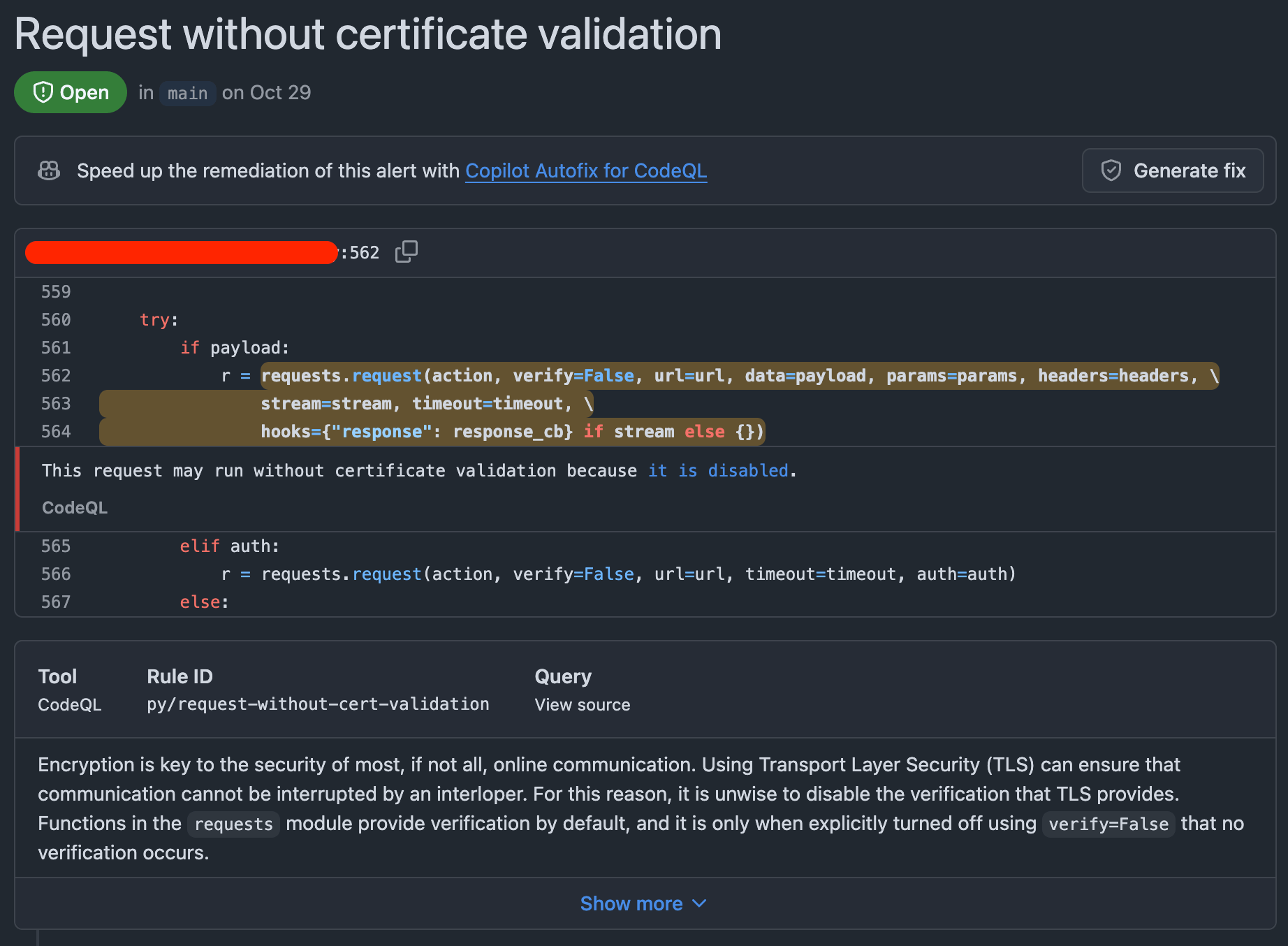

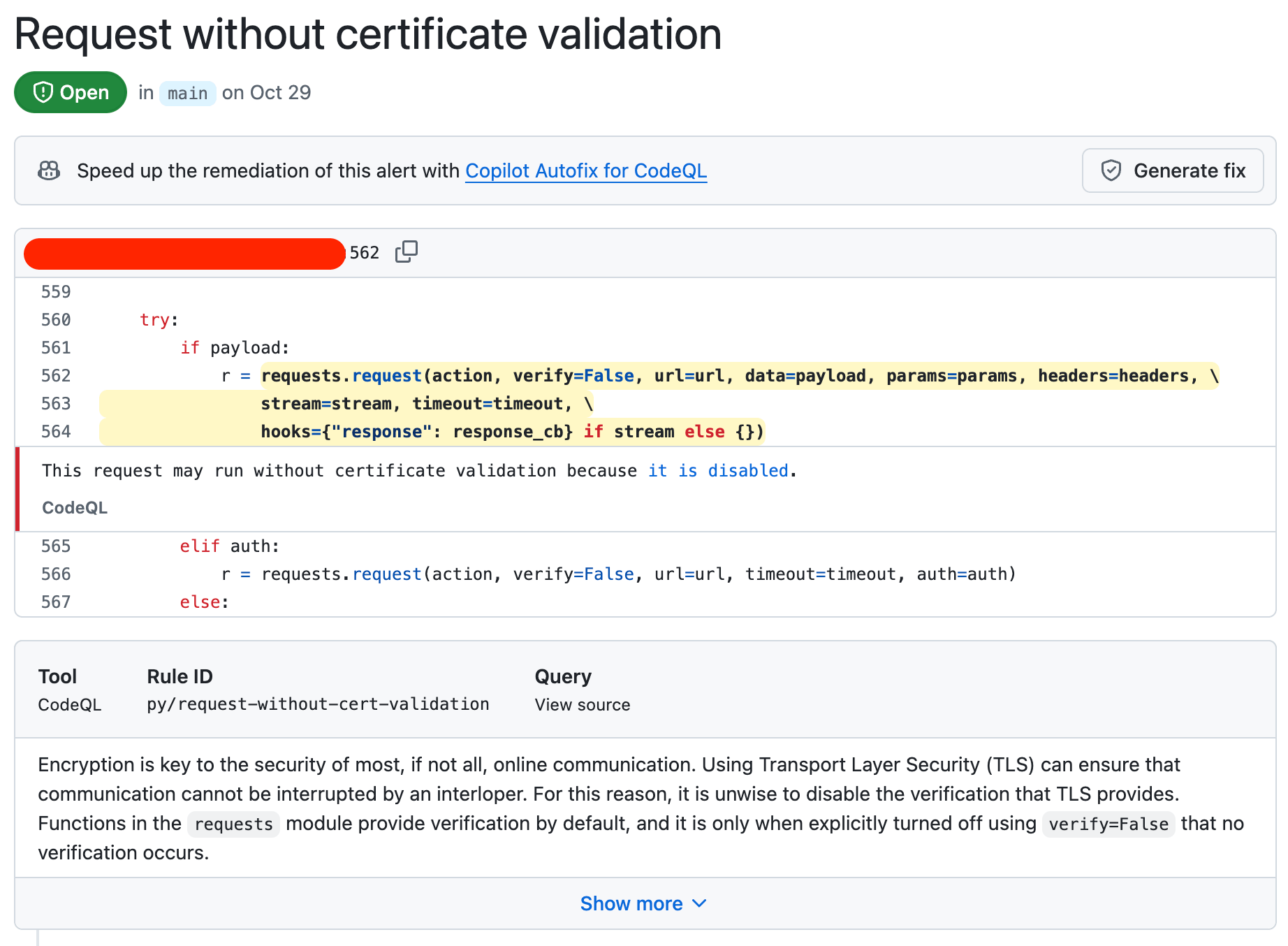

Static code analysis tools

Static code analysis tools look at source code (or infrastructure as code … etc.) for security vulnerabilities. I’m pretty sure every static code analysis tool finds disabled certificate verification most of the time.

CodeQL finding disabled certificate validation

CodeQL finding disabled certificate validation

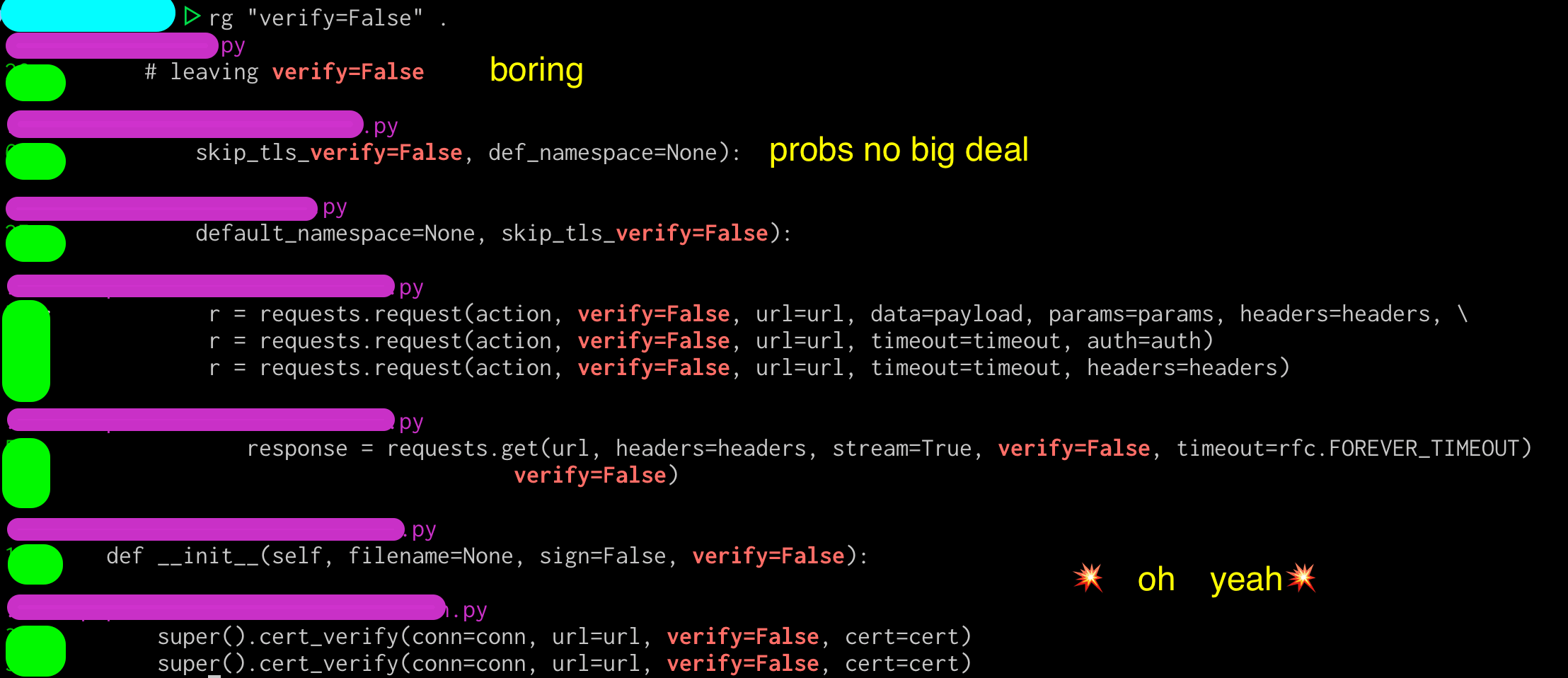

Plain old grep

See how much of the time, it’s a simple string to turn this on or off in most libraries?

This means you can find this with grep or my fave, ripgrep . Here’s an example:

Finding by finding:

- It’s in a line that’s commented out with a

#… boring, but that comment could mean there’s good info in this file. - Situationally (but couldn’t leave unredacted) looks like it’s only used for CI/CD testing … probably not interesting.

- The rest of these findings make me uncomfortable.

It’s easy to pick on any one project or vendor for this, but everyone’s done it. Disabling certificate verification to see if something works narrows down the troubleshooting by a lot. It’s one of the first things I do when troubleshooting too. This is also incredibly common in the private sector side, where SSL meddler-in-the-middle security products cause unexpected failures if the hosts don’t trust the meddler6.

Just … turn it back on. And don’t commit it into your code or configurations. Doubly so when it’s actually important that information is encrypted properly.

I took a quick search of public projects in a prominent software distribution point. Many of these results are in organizations that appear to be owned by companies actively selling into the public sector.

| language or tool | string | results (a/o Nov 25) |

|---|---|---|

| python | verify=false |

18 |

| Shell (and YAML) | --no-check-certificate |

14 |

| git | GIT_SSL_NO_VERIFY |

3 |

| k8s | InsecureSkipTLSVerify |

42 |

… having proven nothing but making myself incredibly uncomfortable, I stopped poking any further … 🫠

This doesn’t mean there are any number of instances of insecure software, as these could be deployed multiple times / as a baseline / not at all / in test. The findings could be in comments only. It is quite possible that everyone who ever deploys software with these findings will change this setting before accepting users. This is proof of nothing …

… but it’s not a good look. It’s sad to see folks market themselves as “all about THE MISSION” and the fast track to 1337 cyberzzzzz security and all that while having these sort of findings publicly visible in code they own.

In my experience, this is always an instant failure. Is it okay? It depends. Ask your assessor or AO for guidance.

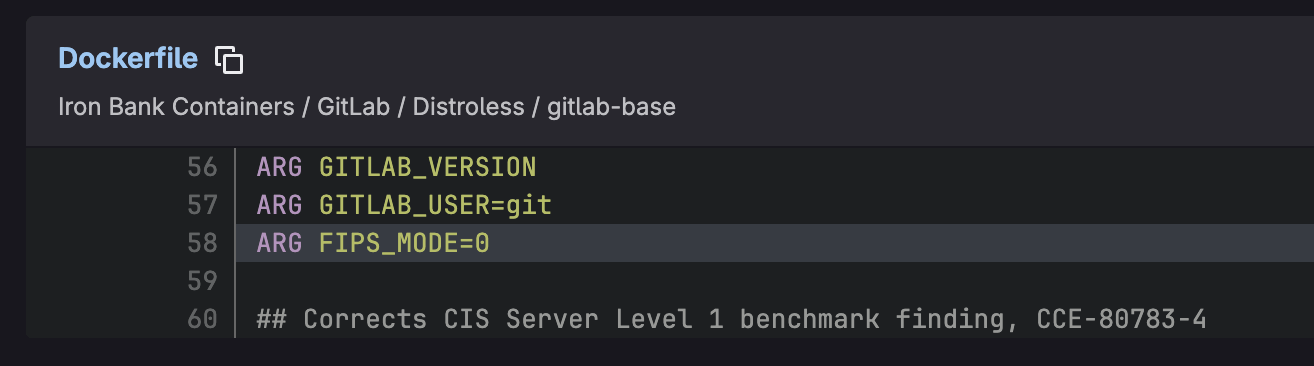

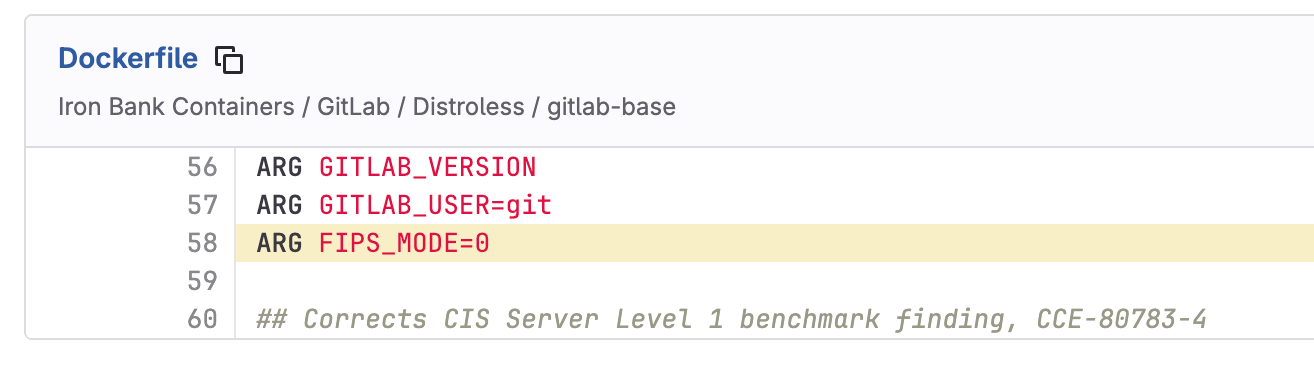

Error #5 - Missing or mangled libraries

If a compliance check only verifies output of a command or that a particular file is present, the room for creativity is problematic. Some fun ways to mangle it in the wild include:

- Editing

openssl.cnf(or other config files) to only offer allowed ciphers - Forcing files to falsify FIPS mode

- Renaming the module provider to say “FIPS” in the name

- Adding “FIPS enabled” or other strings to the output of a startup script

- Using

LD_PRELOAD7 to “just make it work” - A “FIPS mode” check box that does absolutely nothing at all, but looks nice in screenshots

Be cautious when using process profiling tools, too. The end product that “only retains the files in use” means that in practice it could fall back to unapproved methods or fail silently if it needs something not in the profile suite. Cryptography may still work, but is it still validated?

Don’t pay Red Hat with this one stupid trick

This is a Fedora host and a Rocky Linux container. There is no validated anything here, but we … uh … can definitely appear to be operating in FIPS mode.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

test@localhost:~$ uname -a

Linux localhost.localdomain 6.17.9-200.fc42.aarch64 #1 SMP PREEMPT_DYNAMIC Mon Nov 24 21:29:03 UTC 2025 aarch64 GNU/Linux

test@localhost:~$ cat /etc/os-release

NAME="Fedora Linux"

VERSION="42 (Server Edition)"

... truncated ...

test@localhost:~$ openssl list -providers

Providers:

default

name: OpenSSL Default Provider

version: 3.2.6

status: active

As we can see, the Fedora host doesn’t see any FIPS providers. This is expected.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

test@localhost:~$ docker run --rm -it --entrypoint bash rockylinux/rockylinux:9-ubi

Emulate Docker CLI using podman. Create /etc/containers/nodocker to quiet msg.

bash-5.1# openssl list -providers

Providers:

default

name: OpenSSL Default Provider

version: 3.2.2

status: active

bash-5.1# exit

exit

From that Fedora host, launching a vanilla Rocky Linux container in Podman also doesn’t see any FIPS providers. This is expected.

However, we can make it think it does.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

test@localhost:~$ echo "1" > fips_enabled

test@localhost:~$ sudo docker run --privileged --rm -it -v ~/fips_enabled:/proc/sys/crypto/fips_enabled --entrypoint bash rockylinux/rockylinux:9-ubi

[sudo] password for test:

Emulate Docker CLI using podman. Create /etc/containers/nodocker to quiet msg.

bash-5.1# openssl list -providers

Providers:

base

name: OpenSSL Base Provider

version: 3.2.2

status: active

default

name: OpenSSL Default Provider

version: 3.2.2

status: active

fips

name: Red Hat Enterprise Linux 9 - OpenSSL FIPS Provider

version: 3.2.2-622cc79c634cbbef

status: active

bash-5.1# exit

exit

By mounting a file in the container at /proc/sys/crypto/fips_enabled that contains only the string 1, the container now believes it has a FIPS-validated provider for OpenSSL running in Red Hat Enterprise Linux 9.

It does not have this. Depending on your application, it’ll fail if it tries to use that provider or fall back to the non-validated provider. However, your compliance check will see what looks like a validated provider. 🫠

If it feels wrong or deceitful, it probably is. Failure is your friend, telling you what’s wrong to do it right.

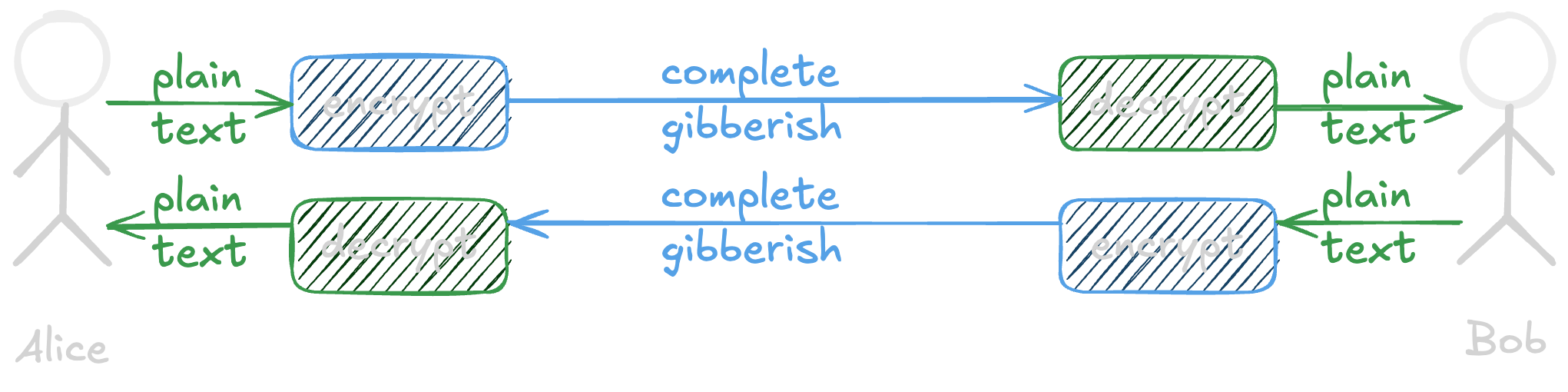

Bonus error - AI will fix it

So, AI is definitely going to fix this, right?

It’s the perfect example of writing software to an incredibly detailed, explicitly defined specification. Maybe one day, but today is definitely not that day.

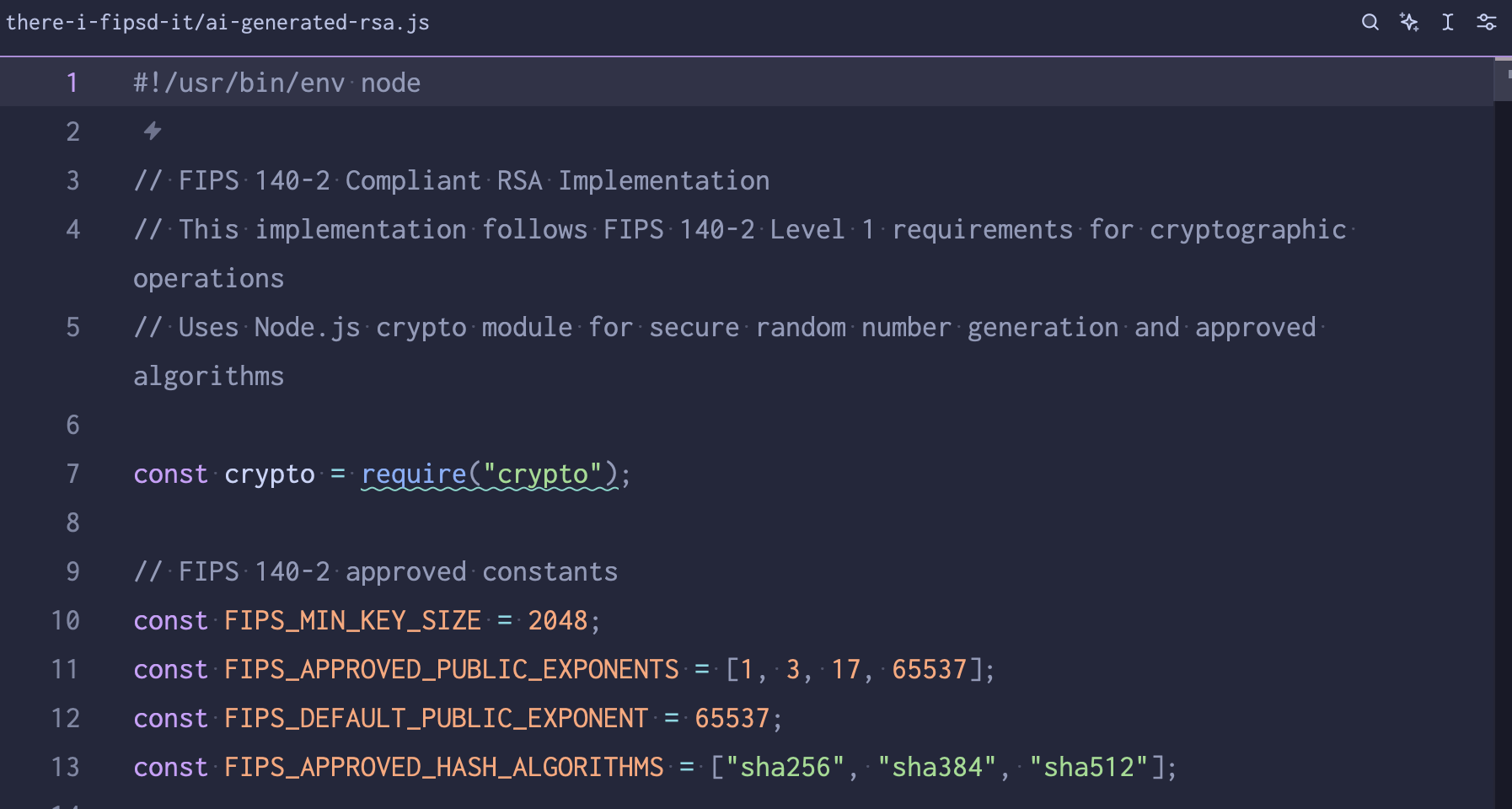

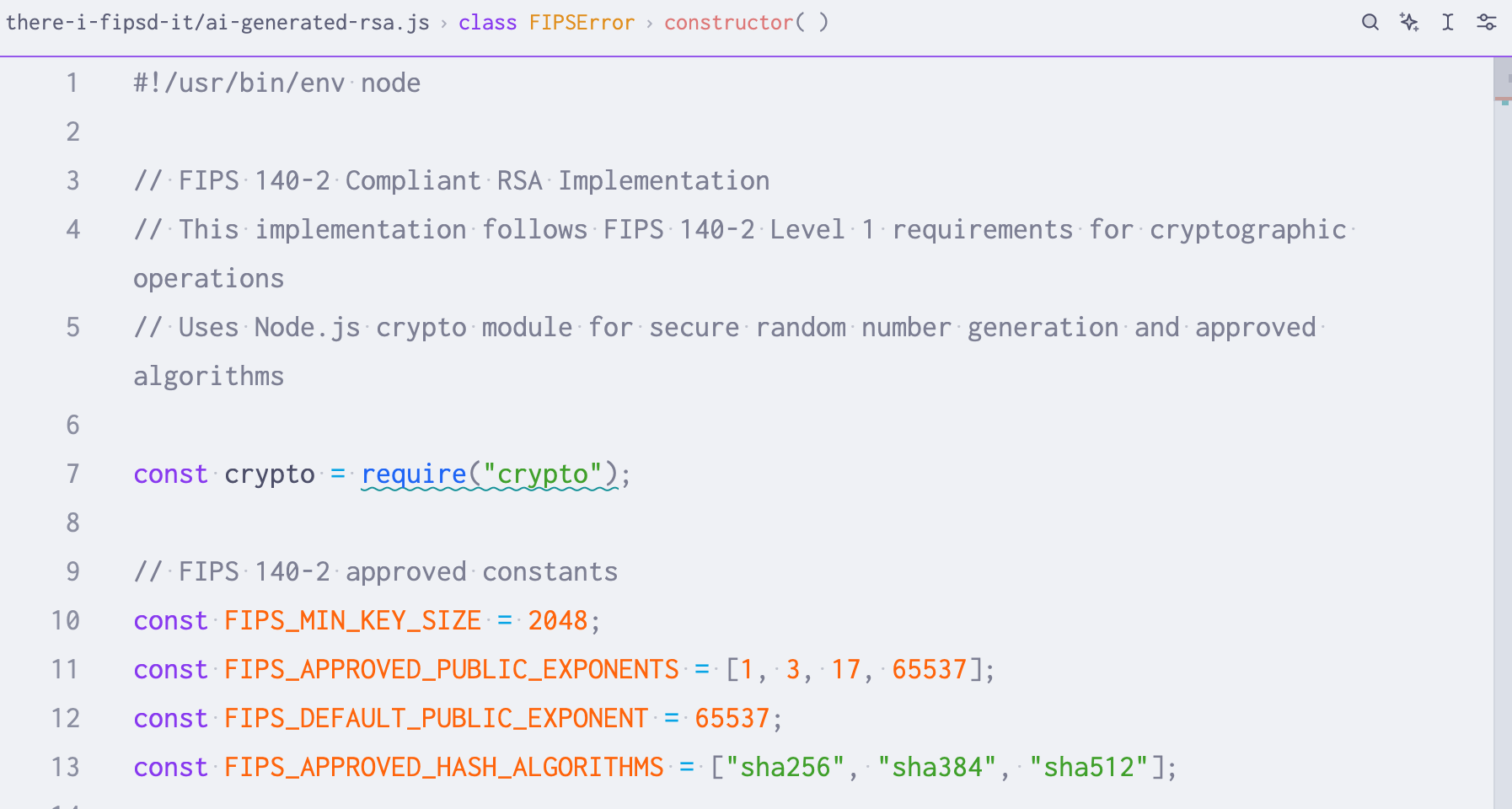

On a whim, I vibe-coded a quick Javascript implementation of the RSA algorithm . My vibe’d source code of shame is public, if it’s of interest to anyone.

RSA is a simple algorithm to implement in practice, but has a ton of well-known security-related caveats documented in that Wikipedia page.

oh no … a prime exponent of 1 isn’t good (line 11)

oh no … a prime exponent of 1 isn’t good (line 11)

The code is beautifully commented, yet full of problems and not good at all. It does say “FIPS” and appears to work, though. I asked for it to be FIPS 140-2 compliant, thinking maybe the models would have more code to have trained on than the newer 140-3 revision.

I’m sure there are a million more critiques of this code, but an exponent of 1 doesn’t encrypt anything. At all. I didn’t even bother looking further when there’s this silliness at the very top of the file.

I’m feeling alright about my job for the foreseeable future, anyways.

AI isn’t a replacement for validated cryptography … no surprises here.

Complexity

So much of the journey to FIPS-validated cryptography depends on the application’s language, framework, and architecture decisions. Many of these were likely made before wanting to support the public sector or adjacent markets that want it. Offhand, here are a few frequently discussed:

- Java isn’t so weird, but the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) doesn’t usually use the host’s cryptography. See the Java Cryptography Architecture, versioned to match your application, for details.

- Rust is super cool and memory safe. To help preserve portability and simplicity, the standard library doesn’t implement cryptography at all. This means you’ll need to do some extra work compared to other languages to validate it.

- Containers are a convenient way to package software and run it as a Linux process. Given that, some complexities to keep in mind:

- It must either bundle a validated source of entropy in the container (new and handy) or pass one in from the host (traditional)

- It must also have the validated module available and in-use by the application

- Containers ideally won’t have

opensslor a shell in the image itself, so you may need to use the API of the library in use or use a sidecar container to verify what’s in use.

- Go has many options for validated providers, but each has varying degrees of support and implementation guidance.

Most application architecture decisions aren’t “one-way doors” that can’t be revisited. That doesn’t mean that the complexity doesn’t spread across the rest of your tech stack, sadly.

Assurances

If all of this makes you feel a bit nauseous, there are practical and hopeful counters to our shenanigans today.

First, it’s becoming easier and cheaper to Do The Right Thing. It used to be that you’d have to download source code, purchase a validated cryptography module, then remove references to old cryptography and add in the new one, then write sufficient test cases, then repeat about a million times to get it working again. This took a difficult-to-estimate amount of skilled engineering time to do. This path is still open to you for the software you write in-house.

Now it’s more common to build on top of services and software that’s already FIPS-validated. Cloud services and commercial software vendors take a lot of this work away for you (for a price, of course). With more of these folks entering the market, costs can go down too.

There are standard security levels for cryptography modules that outline additional measures for a module to verify its’ integrity. There are four security levels that are increasingly stringent, each building on the next.

- Level 1 - Basic security with no specific physical requirements

- Level 2 - Adds tamper evidence and role-based authentication

- Level 3 - Includes tamper resistance and identity-based authentication

- Level 4 - Complete physical security with environmental protection … think over-voltage and space labs, etc.

While we didn’t touch on physical security, adding tamper evidence and resistance does mitigate some of our tampering.

Next, auditors and authorizing officials are getting wiser. Mistakes get harder to hide as folks know what to look for. Audits are also getting automated for cATO (continuous ATO) and FedRAMP 20x. These mean checks will run more frequently. While not everything will be caught by automated systems, it does make life harder to continually be wrong. More eyes and more checks make it harder to stray off an ever-easier paved path.

Making it easy to do the right thing is always a good trend.

While nothing will stop a determined engineer, it’s becoming easier and faster to do the right thing and catch folks doing things wrong.

Parting thoughts

If you’ve been in this space a while … all of this nonsense is to say the obvious.

✨ Security and compliance aren't tightly coupled. ✨

We’ve been working on compliance only today. There are plenty of free open source libraries that may not be validated - but are fantastically secure, well-maintained, peer-reviewed, and simple to use. Check your language and framework for the best options!

Use NIST-validated libraries when needed. It’s probably cheaper to pay for them than writing your own and getting it validated and maintaining it. Read the docs. Make sure you’re using it right.

✨ Ask for a second opinion. Budget for it - in time, money, and people. ✨

Today, we talked about a lot of hard problems.

- Cryptography is hard.

- Shipping code is hard.

- Knowing your data flows is hard.

- Determining what’s security-related is hard.

- Documenting all of the above is hard.

- Maintaining compliance documentation is hard.

- Code review is also hard.

😇 Approach your vendors with "trust, but verify." 😇

The good ones are never scared to prove it.

Resources

- Search - Cryptographic Module Validation Program | CSRC | CSRC

- NIST FIPS 140-3 and Implementation Guidance

- A fantastic example of implementation complexity - postgresql and fips mode

- OWASP guidance on testing for weak encryption

- FedRAMP 20x guidance on using cryptographic modules

- FIPS 140: The Best Explanation Ever (Hopefully)

- Encyclopedia of Ethical Failures is an ever-delightful book of questionable judgement in the DoD

- Cryptography is hard outside of this compliance-focused piece. CVE-2025-66491 (writeup ) is a recent example of a large project (traefik) that accidentally swapped configuration settings between verifying TLS certificates.

- There are consequences to this too, both for a company and for the individuals involved, should any of these shenanigans ship. Here’s a recent example of a manager at a large government consultancy that is charged with a similar crime. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/senior-manager-government-contractor-charged-cybersecurity-fraud-scheme

Gratitude

Many thanks to the folks who provided feedback and reviewed the original slide deck!

- Keith Hoodlet (securing.dev )

- Dimitri John Ledkov (@xnox )

- John Osborne (LinkedIn )

Footnotes

-

Governance, Risk, and Compliance - the department that dots the i’s and crosses the t’s for any compliance framework. ↩

-

Authority To Operate, a formal declaration that an IT system has met security requirements to operate. Can refer to many different sets of security requirements, but most folks I work with are thinking through something built on NIST SP 800-53 rev 5 these days - think CMMC (a subset of these controls) or FedRAMP or FISMA. ↩

-

POA&M stands for Plan of Action & Milestones, a formal document to remedy any shortcomings found in an audit, usually for something based on NIST SP 800-53 rev 5 like CMMC or FISMA or FedRAMP. ↩

-

Defined by RFC 1321 , MD5 is a super common hashing algorithm. ↩

-

In the context of getting software ATO’d, black box pen tests have their place! However, I’ve never seen them used to validate cryptography specifically. Instead, these conversations usually happen with an architecture diagram and source code and any other supporting documents. YMMV 🤷🏻♀️ ↩

-

Meddler-in-the-middle security products include “Zero Trust” products or Cloud Access Security Brokers. There’s a reason these products come with professional services. It’s incredibly easy to overlook someone’s cloud environment and end up with folks disabling SSL verification, as I’ve been over before. ↩

-

In Linux,

LD_PRELOADforces specific shared objects to be loaded first. It’s used to override existing functionality without changing the source code. A funny misuse of this islibleakmydata, but I haven’t seen that one in the wild. I have found folks trying to override a FIPS module with a non-FIPS one … situationally, this could be okay if it’s a “non-security function”. Ask your assessor for guidance. ↩