Enterprise chargeback - can we do this?

How do you know how much each business unit is using across any number of licensed software or consumably-billed SaaS or compute products? Let’s scope actually doing this having done it before. It sounds a lot easier when I started than it was when finished, yet it’s one of the most common stories I’m asked to tell. There’s some trauma here, but lots of lessons learned too. 😅

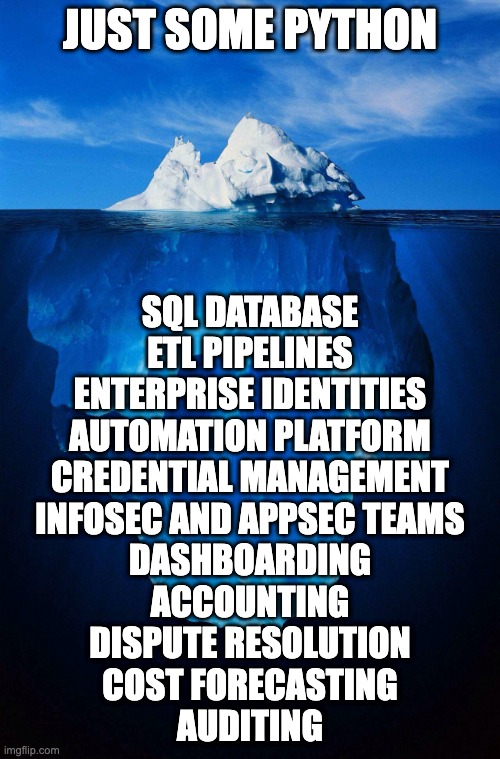

This is the story of my “iceberg slide” - or how to build and run an enterprise chargeback system. It served the needs for

- tens of thousands of users 👥

- about fifty tools 🧰

- a dozen business units 🗃️

… in one of the most regulated business environments ever - federal defense contracting.

🐣 But it didn’t start out that way! 🐣

It started as a science project, then grew to serve more needs of the business.

How this started

Giant companies (tens to hundreds of thousands of employees) live a weird contradictory existance. Each business unit is a fiefdom.

✨ It’s fantastic that each group can independently solve their problems as they see fit. Tons of business books are written about this as a strategic advantage. Go read them if you want.

🤦🏻♀️ It’s terrible in that it codifies inefficiencies. Reusing expertise and innovation across business units is as minimal as their cross-communication and curiosity on what other units are doing. Bulk license negotiations are economical for software purchases, but not everyone needs every tool at every time.

So how can we get the best of both worlds? Use our large scale get cheaper licensing in bulk purchases, but how to also account for that to the client’s billable work? Who’s using what applications? How can we allocate that cost back to each business unit

Exploring the data yielded some profitable insights into the developer talent in-house and how that could map to inbound contract work, in addition to some small savings for bulk license consolidation. What other value can be extracted from this usage data?

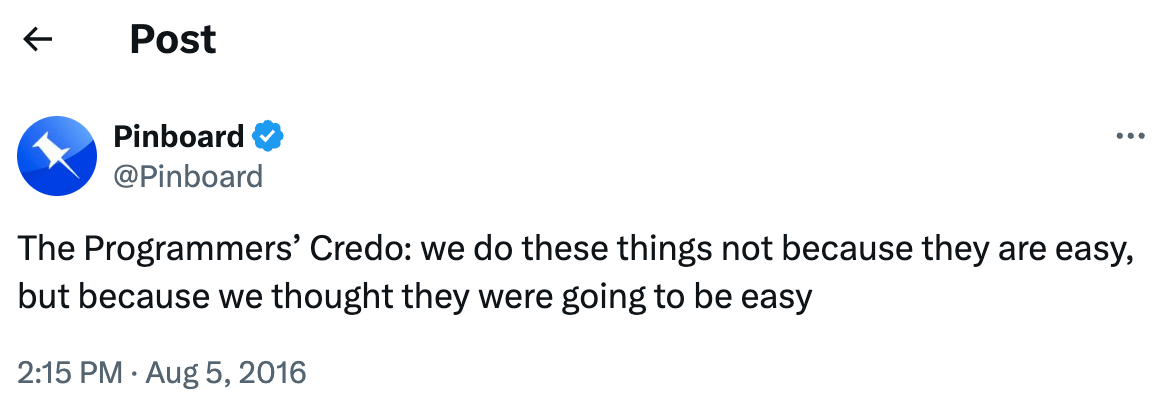

This was going to be easy

The exploratory scope was simple. We’d handle a few self-hosted services and use a database to hold that data. Each of these services has an API. This should be a simple CRUD1 app.

I’ll use Python and Postgres, two unquestionably boring choices. I am a reasonably clever engineer2.

This should be easy, right?

The first try

The first prototype was simple and worked!

Each pilot service had simple REST APIs, so it was easy to write a script for each service. Every data point returned by each API had a field in a raw_service table in the database. The script would then paginate on that API until the end, then insert it into a table in a database. That’s it! 🎉

flowchart LR

A(fa:fa-database PostgreSQL database)

B(fab:fa-python a few Python scripts)

C(fab:fa-jira Jira Data Center)

D(fab:fa-confluence Confluence Data Center)

E(fab:fa-github GitHub Enterprise)

F(fab:fa-slack Slack)

subgraph "My Work Laptop"

A --- B

end

subgraph "Pilot Production Services"

B --- C

B --- D

B --- E

B --- F

end

It was so simple that we now had ✨ a whole bunch of problems to solve quickly. ✨

Names are literally the worst

Take a moment to read the classic “Falsehoods Programmers Believe About Names ” … I ran into many of these problems before finding this beautiful piece explaining all the trouble I was about to find.

Now with a few weeks of data to work with, we’d set out to try to figure out how many folks use all of the pilot services.

Until names showed me how many problems they can cause. 🤦🏻♀️

Programs interpret names differently

Each program, despite using the same human being, interprets names differently. Take the example of Alice Z. Smith with an employee ID number of 432109.

While each service in the pilot used the same central identity provider for SAML authentication, each program interpreted that identity differently. This meant that the same human being could have the following names:

-

smith_alicewas the standard normalization and about half the services used it -

asmithwas used by a few legacy services -

smith-aliceas GitHub specifically cannot handle the underscore (_) character3 -

alice_smithbecause someone configured a chat tool to be “human friendly” and never considered that display names don’t have to match identity, but it was already too late to change it -

432109since employee identity numbers are unique and won’t change - … and more varieties I’m sure …

Names are not unique

Let’s try to figure out what to do about the fact that there are eight different humans that share the name john smith at the same time in the same company. Now add in all of the folks named john smith that left the company before you started and account for the ones that will join after this system is up and running.

Most identity providers accommodate this situation by adding a number to the end of the name such that we have smith_john and smith_john1 and smith_john2 and so on. It’s critical to figure out how each system that ties into each system you’re trying to measure resolves this.

For example, john_smith6 is provisioned in services A and B and C. Do these systems all recognize him as the 6th of his name in the central identity provider? More than likely, he’s 1st in one system and 10th in another. If this isn’t uniform across all services in scope, it adds another dimension that has to be provably untangled. 🕵🏻♀️

Employee IDs aren’t guaranteed to be unique either

If there is ever any recycling or reclamation of employee ID numbers, it’s no longer great as a unique identifier. Once that reclamation period passes, another human will become 432109. These cases may be small in number overall when dealing with tens or hundreds of thousands of users, but they don’t disappear and slowly grow over time to provide meaningful data drift.

Don’t recycle employee IDs! It’s incredibly difficult to untangle this across systems when it’s reasonably assumed to be a unique identifier for all time. 🤦🏻♀️

Humans change their names

Folks change their names for all sorts of reasons. Not all systems handle this gracefully.

Let’s say that jane doe was provisioned as doe-jane in a system. doe-jane still exists, even if they change one or both of their names. This means that you’ll need to account in each system for

- Username changes, preserving the account in each system

- Username changes, creating a new account and locking the old one for any later audits

Both of these are valid choices, but have consequences later on for chargeback, auditing, and license consumption.

Figure out names as best you can first! These human identities form the primary key that ties consumption across time and services. Changing this is both inevitable and beastly enough to try to avoid as much as you can.

Machines also have identity problems

Non-human identities also consume various resources or licenses, so we have to figure out how to track these too. It’d be convenient to assume these are easier to govern. It’d also be very wrong.

The same problems of name duplication and changing and lifecycle management occur here too. If each system allows it, creating a uniform schema sounds tempting … but in practice, uniformity across a big enterprise for machine identities is a big investment to maintain.

Choose your battles. Having a naming convention for all machine identities in a huge company is neat. It’s a lot of work to keep up with, though, and likely not the best use of time for billing integrity or security.

Extract, load, then transform

Dear reader, I did not get to re-architect dozens of enterprise-wide systems to create One True Identity Manager. 😂

None of these problems are insurmountable, but they all add up to be annoyingly specific to each system. These concerns all got documented, then mostly fixed by the transform part of ETL scripts in the PostgreSQL database.

Each service now had two tables, with a set of scripts governing how the data is normalized and deduplicated and otherwise tidied up. To make it somewhat consistent, the tables were renamed raw_servicename and servicename. The scripts would be written such to only modify one service and would have that servicename string in their name as well.

erDiagram

RAW_SERVICE_ONE_DATA ||--o{ SERVICE_ONE_DATA : becomes

USER ||--o{ SERVICE_ONE_DATA : ties

RAW_SERVICE_ONE_DATA {

string username

date dataPullDate

int usage_type_one

int usage_type_two

int usage_type_n

}

USER {

int 🔑UUID

date dataPullDate

binary isHuman

string fullName

string email

int chargecode

int employeeID

string serviceOneUsername

string serviceTwoUsername

string andSoOnAndOn

}

SERVICE_ONE_DATA {

string username

string 🔑UUID

date billDate

int usage_type_one

int usage_type_two

int usage_type_n

float price

}

At a high level, any given service’s data looks like the diagram above. The Python script scrapes API endpoints runs once a month, then inserts data into the RAW_ table. Given so many identity instabilities, it seemed best to create a UUID and tie it to the many forms of one person’s identity - treating “identity” as a service that was fed by a bunch of other providers the same as any other service.

If it sounds like we have an enterprise data lake on our hands, it’s because that’s what happened! The little puddle of information I’d set out to gather quickly grew into a pond … and then a lake. Problems where it’s possible to code my way out of were never The Hard Problems of enterprise chargeback. 😢

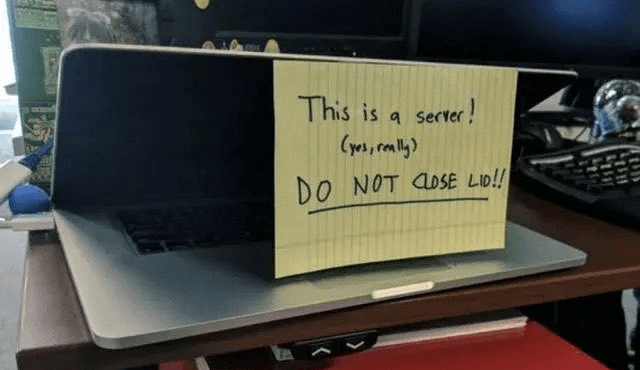

Get this off your laptop

So far, this was all on my work laptop. Python scripts were run manually as I’d iterated over what to gather and how to avoid various timeouts. DBeaver provided a way to browse the data and develop the ELT pipelines and stored procedures. This could create quick reports for feedback from the various leadership folks who’d be using the data.

It’s also wildly inappropriate for a production system.

- Provision a new database server

- Harden the operating system and database

- Figure out firewall rules

- Migrate data from the laptop to the server

- … and so on …

Now that it’s proven possible and probably valuable, this step should be boring. As a lovely bonus, our internal IT team also set up some automated backups of the server.

Next - let’s do databases and such better this time, setting the foundations to grow from a handful of services to a much more robust system. Also, let’s survive the annual re-org!

Footnotes

-

Short for “Create, Read, Update, Delete” or a simple application that does basic operations on business data. ↩

-

Humility has never been my strong point, but this project thoroughly humbled me in each of the not-strictly-technical challenges. ↩

-

This was true at the time and is still true while self-hosted. Now, GitHub.com can use quasi-private partitions called “enterprise managed users” where the underscore (

_) character and a string after it are used to determine which identity provider is used by each business partition. ↩