Containerized CI at an Enterprise Scale

This post is slides + commentary from a talk I gave at Cloud Native Colorado on November 21st, 2022 about some of the weird ways you can blow up your cluster and your sanity once continuous integration jobs are added into Kubernetes, lessons learned in how to avoid these problems, and why it’s still worth all the effort to containerize your build system (slides as presented). Kubernetes saves a ton of time and heartache maintaining a shared build infrastructure, but here’s a few ways it’s not your average application.

Introduction

Hi! I’m Natalie and I talk a lot about making the lives of enterprise admins easier, especially in heavily-regulated environments. It’s continually fascinating how in the very places that need automation the most to make systems safer and faster and more reliable, it can be so much harder to pull it off successfully. You can find me online at my website, some-natalie.dev, or on GitHub @some-natalie .

I’ve made some pretty monumental fun mistakes out of hubris and I’m here to talk to you about some of them I made in my first grown-up, not-a-lab, real users are on this thing(!!!) use of Kubernetes. I got a chance to design and build a system for GitHub Actions for the self-hosted environment I led for thousands of users. The problems I faced turn out to be pretty common and I see them in many other teams trying to do the same thing.

In working as a sysadmin, my first introduction to systems that build/deploy/maintain code was a series of scripts that ran on a cron job - checking out, building, and updating code on a web server nightly. It was fun to watch devops transform the idea of “devs make” and “ops execute” into a more unified idea of software ownership - because every system I worked with that followed this pattern was terrifyingly fragile and pretty much everything that came later was an improvement on it.

As these systems scaled, I found myself adjacent to a huge shared Jenkins installation kept in line by dozens of Puppet modules. In wanting to avoid tons of configuration management code in the form of Puppet with the new system using GitHub Actions, I instead went down the path of tons of environment creation code in the form of Docker files. Still not sure how much of an improvement this represents on the code-management front, but the power of ephemeral and version controlled environments saved a phenomenal amount of administration overhead (my time) and developer time by creating reproducible builds.

I have some biases, so let’s get those out in the open before we go on.

First is that people time is almost always more valuable than machine time. Assuming an average developer in the United States costs approximately $150k per year1, that’s roughly $75 an hour. If they’re held up on a requested item or support ticket or a long build for a couple hours, this cost adds up fast and is hard to account for. Even harder to calculate is the retention cost of frustration on slow, heavyweight processes. Like many in our profession, I have a pretty low tolerance for toil work . (source linked from the slide here )

Next is that simple solutions are better than complex ones, but complex solutions are better than complicated ones. The source for this is Python’s PEP 20 - even if I chose a complicated approach to this problem (Kubernetes), at least it was thought through. It turns out that having a bunch of teams with different dependencies share a system to build their code securely, reliably, and quickly is hard and that makes what “simple” is a sliding scale. This challenge is at the heart of the anti-pattern we’ll visit a couple times throughout the evening.

Much of my career so far has been in a business’s cost center - like internal IT departments that cost money and don’t bring in any money. As such, expenditures from software purchases to headcount is a bit of a fight to justify. The systems I’m describing are typically the responsibility of a team empowering developers, which usually falls into that “cost center” category. This means that avoiding toil work by automating as much as possible has an outsized impact to quality of life for administrators and for developers.

an appropriate reaction to seeing 800 packages listed on

an appropriate reaction to seeing 800 packages listed on yum update

Lack of investment or institutional interest doesn’t mean this problem is worth ignoring. If every company is a software company2, how that software is built becomes critical to the business.

A build environment is like a kitchen. You can make all sorts of food in a kitchen, not the one dish that you want at any given time. With a simple set of tools and time, a dish can transport you anywhere in the world. If it’s you and some reasonable roommates, you can all agree to a shared standard of cleanliness. The moment one unreasonable house guest cooks for the team and leaves a mess, it’s a bunch of work to get things back in order (broken builds). There could also be food safety issues (code safety issues) when things are left to get fuzzy and gross.

Imagine being able to snap your fingers and get a brand new identical kitchen at every meal - that’s the power of ephemeral build environments. Now imagine being able to track changes to those tools in that kitchen to ensure the knives are sharp and produce is fresh every single time anyone walks into it - that’s putting your build environment in some sort of version-controlled, infrastructure-as-code solution.

Without routine maintenance and some supply chain management, most shared build systems eventually end up on the sysadmin’s equivalent of Kitchen Nightmares. Sadly, no charismatic know-how shows up to fix everything - but Kubernetes does!

Nested Virtualization

The first set of problems revolve around nested virtualization - think “Russian nesting doll”, but with containers and (hopefully invisible to the users) virtual machines.

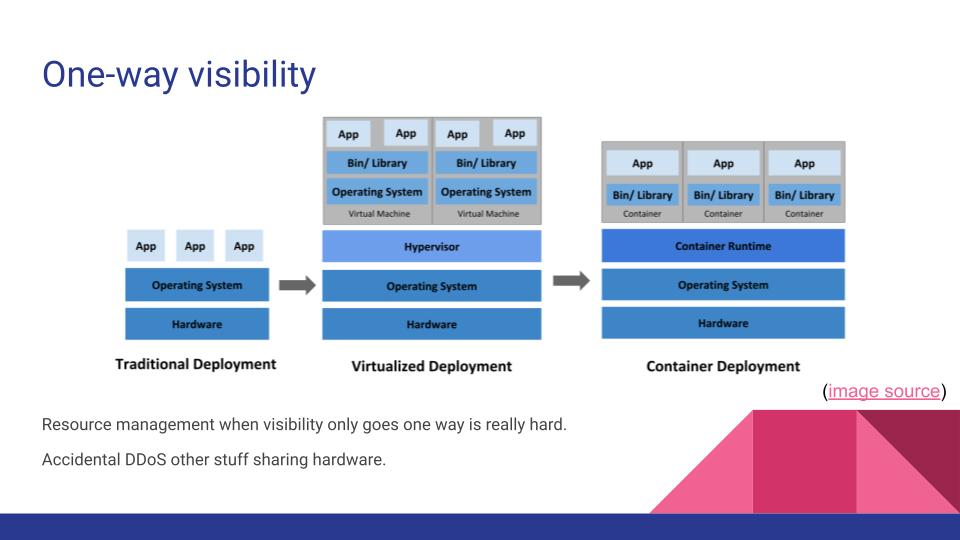

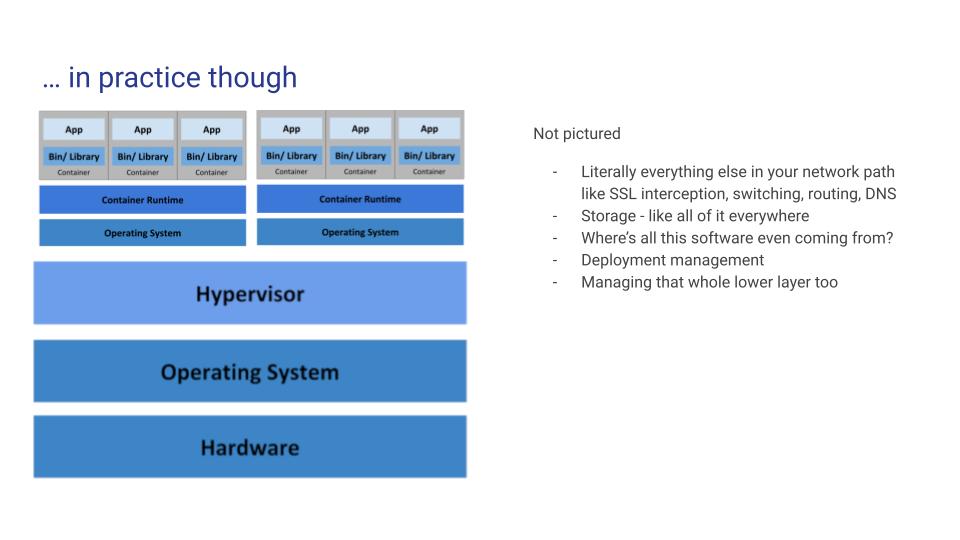

Let’s take a moment to make sure we’re all on the same page about terms and such. This image is from the official Kubernetes docs (link ) and it’s well worth the read, since we’re here and not in a room together. On the left is where that system working from a cron job would be, then in the middle would be the system using Jenkins + Puppet on VMs that I’d hoped to improve on, then on the right was what I was hoping for.

The challenge here is that when visibility only goes one-way, resource management gets exponentially more important with each additional layer of abstraction. A virtual machine hypervisor can see some load and other statistics from each VM it’s running and schedule accordingly in the cluster or move it around as needed to balance load across disks/CPUs/etc. The virtual machine cannot see other VMs running on the same hypervisor.

The same is (mostly) true of pods in Kubernetes. Pods don’t share awareness of all other pods, but the Kubernetes scheduler has an understanding of the resource requirements of tasks and resource utilization of nodes. However, the Kubernetes scheduler is running within a VM and that isn’t talking to the hypervisor and what it wants to put on that shared hardware.

This is important because in my experience, on-premises clusters tend to look like this 👆. I didn’t have dedicated hardware, but added this to co-tenanted VMs in a hypervisor, meaning that the architecture diagram I ended up with looked more nested than first drawn out. It’s possible that as the Kubernetes scheduler is moving pods around to balance across the nodes, the hypervisor’s load-balancing logic might also be trying to do the same - moving nodes around within the servers. I accidentally DDoS’d some other production services with vMotion until I learned to set the affinity correctly. Understanding what else is sharing that hardware outside of the Kubernetes cluster, how it reacts to online migrations to other hardware, and how to set things up to not interfere with each other is both important and hard.

What’s not in this picture is equally important - what’s the network path for a request from a container, outbound to the internet?

- Container

- Container runtime

- Node OS

- Hypervisor

- Host machine

- < insert your company’s whole network security stack here >

- Internet, maybe?

Then all the way back upwards to get back, for each and every packet.

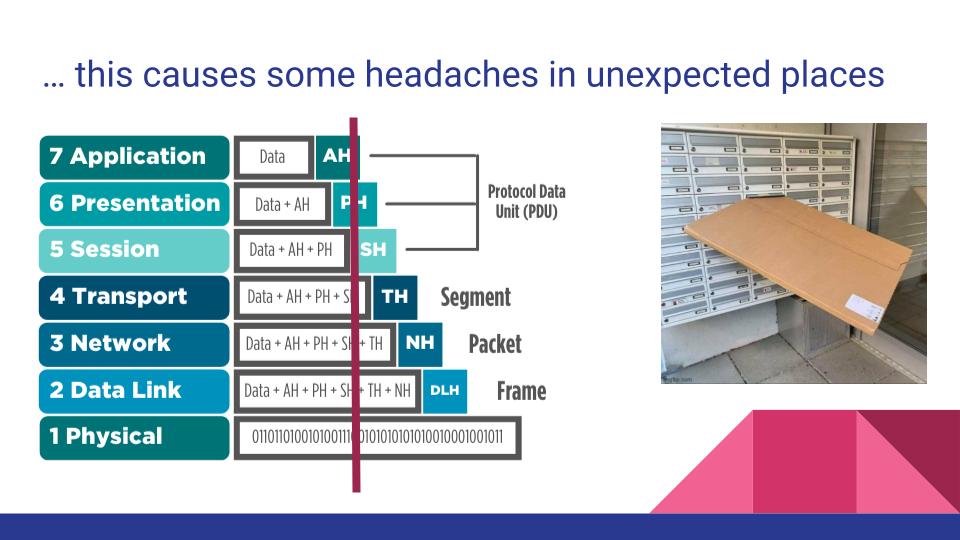

All about maximum packet size

Taking a step back to our network fundamentals, at each of the steps above to get from container to network, some amount of packet headers are coming off and getting added to route to that next step. Each of those steps has a maximum size that it’s able to handle, called the maximum transmission unit (MTU). In my handy diagram above, I drew a red line representing some size past which packets can’t continue. To make matters more fun, not all packets will get dropped, making it a difficult problem to identify and troubleshoot.

In theory, this really shouldn’t be as much of a problem as it is. There’s not one, but two, fantastic ways to address the maximum packet size. They don’t always work as expected in this case.

The first is Path MTU Discovery, codified by RFC 1191 . This relies on the point along the packet’s journey that it gets dropped due to excess size to send an Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) message back to the sending application saying “hey, this is too big, send me something smaller next time”. A really cool writeup of how this works from Cloudflare is here . Without that message, the container (and thus the user) has no feedback or way to decrease packet size - just frustration. The reason it often doesn’t work as anticipated is that most large companies will have pretty much everything in the network configured to silently drop all ICMP messages, feeling that network security has improved through obscurity.

The second is TCP MTU Probing, with the latest revision in draft with RFC 8899 . This works based on “getting the hint” that the packet is too big because it fails, then sends incrementally smaller packets until the correct max size is deduced. Red Hat’s developer blog has a fantastic writeup explaining how this works and how to set it up here . This usually works, but has the drawback of being slow - because each pod is ephemeral, each pod and each user’s job goes through this process at every run. Additionally, while some processes will tolerate this negotiation until it finds the right size, others silently hang/fail. Since the pods are ephemeral, the process that the user wanted never gets a chance to work.

To counter this, I recommend setting the maximum MTU size explicitly in your cluster (and pod, for that matter). I’d love to show you a simple code snippet of how to do this with the correct sizing, but there’s about a million variables based on what else is in your network and what CI tool you’re using.

Specific to GitHub Actions in Kubernetes, actions-runner-controller has some guidance on setting the MTU size explicitly here .

Managed services, such as Azure’s AKS or Amazon’s EKS , make a lot of these problems disappear. Specifically, a lot of the problems related to managing your hardware, hypervisor, and VMs that host/run Kubernetes. It also takes away resource allocation problems, allowing you to scale as needed instantly.

On a self-managed cluster, if it thinks it has 100 virtual CPUs for worker nodes, but in truth, you’ve used some fancy hypervisor setting to over-allocate - this’ll be good until it actually needs to use everything it thinks it has but can’t provision it. The Kubernetes scheduler is only as smart as what it can see. A managed service handles scaling for you invisibly.

That’s not without a cost. Cost planning and optimization for managed services is an entirely different exercise than owning/operating datacenters. You should contact the account team of the service(s) you’re looking at for a better understanding of how charges are incurred because that’s way outside the scope of this talk! 😀

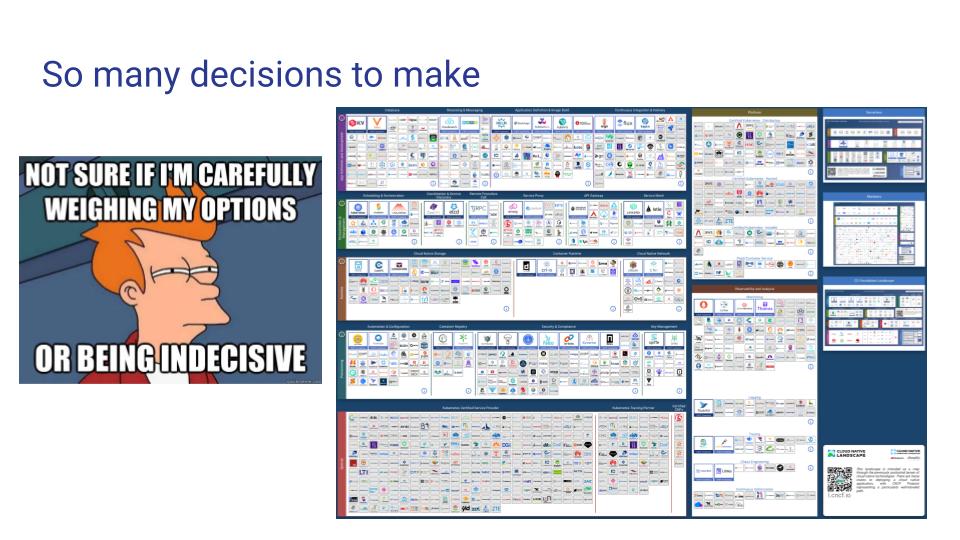

A managed service or a commercial “off-the-shelf” Kubernetes distribution will also provide at least some opinionated guidance on all the choices to make in standing up and running a cluster. The picture to the right is a snapshot of the Cloud Native Computing Foundation’s landscape (link ) and that’s a fraction of the decisions to make in going from 0 to k8s, assuming what’s needed and not is even known going into it. It’s daunting (and exhilarating).

Once the basic infrastructure decisions are made, there’s one more thing to think through that drove the large difference between the resource requests and limits for the runners that I recommend for hosting on-premises. Predicting the resource usage of any particular job/task/build/whatever is pretty hard when you have a ton of different ones. One of the benefits to this large delta is that the quick little tasks that don’t require a lot of compute can go anywhere, while the heavy usage pods can be moved around on the nodes by the scheduler to optimize longer-running jobs. I also set the deployments that handle build jobs as BestEffort or Burstable, allowing them to be evicted when more important tasks in the cluster come up3.

If you’re using Kubernetes within a VM infrastructure, the worker nodes can be moved around as needed to make the best use of the physical compute. When this goes wrong, it can cause all manner of cryptic error messages so make it a habit to always check resource utilization first.

In summary, here’s a few things to keep in mind - first is that ✨ containers are not VMs ✨ and using them like VMs sometimes reveals fun edge cases to explore in a river of user tears.

This guide on anti-patterns of cloud applications is helpful. I specifically run into the following frequently:

- Noisy neighbors (for self-hosted clusters)

- Extraneous fetching (pods are ephemeral, so lots of network traffic)

- No caching (making sure the pods are always configured to use the caches you have is frequently overlooked)

The two decisions to make around audience size versus pod size - big pods or lots of deployments of small pods - are going to be discussed more in the section on ephemerality, but each work well technically and can struggle depending on the “people and process” aspect of engineering depending on how the team works. There’s also an ever-increasing number of people and processes that become stakeholders to manage, adding to the fun.

Privileged Pods

Now that we’re up and running, let’s talk about ways the word “privilege” comes up with user requests. As mentioned earlier, ✨ containers are not VMs ✨, so the same security postures we had for VMs don’t apply equally here.

🔒 Kubernetes security is one of those topics we can spend hours on and maybe one day, we will but today I’m going to leave you with an overview and some things to think about for this use case, as well as the amazing documentation .

The first point is that a privileged pod does not always mean that a process has root or sudo access inside the container - and vice versa! It might mean that it’s easier to obtain one given the other, though. For the rest of this talk, we’re going use the convention that “privileged” means the pod’s security context is set to Privileged - meaning that system-wide trusted workloads are run by trusted users. Likewise “rootful” will mean that the entrypoint script/command, build job, configured user, etc. either is root or has sudo access.

There’s a decent amount of overlap in how these two concepts are used in practice, adding to the confusion. To help mitigate potential escalations and untrusted workloads, it’s helpful to keep defense in depth in mind, layering controls and allowing minimal permissions to prevent container escapes and other security incidents.

How Linux handles permissions (in a nutshell)

We’re going to need to know a bit about how the Linux kernel handles permissions. Containers are not a kernel primitive, but a combination of a regular process and some special guardrails. This means that Kubernetes is scheduling processes for multiple projects on shared hardware without the isolation of a virtual machine because ✨ containers are not VMs ✨.

This isn’t the end of the world, but our toolbox has changed compared to managing virtual machines. Let’s take a quick look at some of those tools.

-

Capabilities define what a process is allowed to do. Rather than an all-or-nothing approach of being root or not, capabilities allow users to selectively escalate processes with scoped permissions such as bind a service to a port below 1024 (

CAP_NET_BIND_SERVICE) or read the kernel’s audit log (CAP_AUDIT_READ). We’ll talk a little bit more aboutCAP_SYS_ADMIN, a special one that comes up frequently with debuggers or older build tools later. -

Namespaces are resources the process is allowed to see, and they’re defined by syscalls. Common namespaces are

timeoruts, defining the system time and hostname respectively, as well as a few more defined in the linked documentation. More importantly,cgroupsare defined here. - Cgroups (short for “control groups”) define what the process is allowed to have via a weird filesystem. There’s two different versions to be aware of here, but the differences between them are way outside the scope of this talk. The big takeaway here is this is how the kernel knows to limit a process to only have so much memory or CPU time.

- Overlayfs is that stacking filesystem that containers use. Important to note these are mounts and get a little weird later on in this talk.

- Mandatory Access Control implementations like SELinux or AppArmor play a huge part in security too, but that’s a huge topic we’ll have to save for another day. (Just don’t disable it, okay?)

A “namespace” in Kubernetes is an abstraction to provide some permissions isolation and resource usage quota within a cluster (such as deployments, secrets, etc.). It’s commonly used to divide a cluster among several applications. A kernel namespace is a low-level concept that wraps system resources in such a way that they are shared but appear dedicated.

This change means users migrating from VMs that assume their jobs have root access might not “just work” in this new system without some changes. Resist the temptation to immediately grant them privileged pods and figure out if we really need it first. Unless you’re in a huge rush to decommission the system they’re moving from, it’s usually okay to spend some time messing with permissions and dependencies to allow their code to compile without privileged access first.

Let’s talk through a couple common places this comes up.

Docker-in-Docker

The first is Docker-in-Docker - or Podman-in-Podman, or any other combination of a container running in a container. It comes up most often when your users want to build containers, but they’re in a container.

Docker in Docker requires privileged mode and there’s no ambiguity here. The official image even states it, and the links to what exactly --privileged means are here . This is one of the places where your container tooling starts to diverge, as Buildah in Podman can be done without privileged mode, as outlined here . Note the trade-offs between performance and security.

There’s another very common use case specific to GitHub Actions. An Action can be JavaScript, any scripting language or combination of other Actions (called “composite”), or a Docker container. These container Actions build that container(s) on each job, then run it. While some container Actions may work with an alternate runtime, like Podman using podman-docker to alias the two, it assumes Docker and any deviations may mean the Action won’t work as expected.

There’s a couple reasons building containers in CI when your CI system is containerized is weird, and these are best outlined by Jérôme Petazzoni in his blog post “Do not use Docker in Docker for CI” . It’s well worth the time to read, and then re-read.

In practice, the two problems that I see most frequently are

- Inner and outer Docker don’t share a build cache. This results in about a billion image pulls all the time. I’ve seen a few ways around this, including using a persistent volume to share a cache across pods (but this means we’re persisting resources between pods/jobs/users, outlined here for actions-runner-controller) or trying to ship pod images that have some common images already cached (which results in enormous images).

- To avoid using a privileged pod, an administrator will bind-mount the privileged Docker socket at

/var/run/docker.sockto share it within a container. This lets a container spawn other containers on the same host, share a build cache, etc. This path works great for a single team on a dedicated CI system that isn’t using Kubernetes or worried about other jobs sharing a privileged runtime or cache. A couple problems with this path include the recent removal of the ability to do this from Kubernetes (more here ) and the idea of sharing a privileged socket between untrusted workloads being less than secure.

From experience, I’ve found a couple practices to make this less painful.

- Use rootless Docker in Docker when you need Docker inside of a container, like GitHub Actions that ship as a Dockerfile. This still requires a privileged container, but you should be removing the ability to mess with mounts, sudo/su to root, etc. There’s much more about rootless Docker in the docs here . You can also use SELinux/AppArmor/etc to lock this down more. The tradeoff here is that an admin must have all the needed software available in the image first, as users don’t have the ability to run

yumoraptto modify software either. - There’s other neat tools to build and push container images without privileged access in Kubernetes if that’s all that’s required, such as using Buildah within a container as outlined earlier.

- Have a pull-through cache on your network and make sure the pods all use it. It still means that your users will be pulling plenty of container images over time, but at least the bandwidth to do this is all local. This balances the need for speed (and not getting rate-limited) with a more reasonably sized image.

Next up on the whirlwind tour of user requests is hardware enablement. First is understanding we’re way into Kubernetes implementation specifics now, but there’s a (beta) feature to be aware of called device plugins to accomplish exactly this thing. It gives the kubelet the ability to understand specific hardware capabilities (like GPUs or special network adapters) of the host and provide pods access to it.

- GPUs specifically have documentation here , but this is still experimental.

- Anything requiring direct access to the host’s network stack, such as wanting a specific NIC or run a packet capture.

- Hardware testing, as mounting or unmounting anything in

/dev/is a privileged task. - Accessing files on the host without a storage abstraction sharing it.

In short, maybe these tasks shouldn’t be moved to a shared Kubernetes cluster, but some of these needs can also be mitigated with additional storage shares or using a device plugin instead of relying on direct access to the host.

A quick note - a pod that isn’t run with privileged but has CAP_SYS_ADMIN is still privileged. This slide shows a small subset of what this capability allows a process to do. Don’t fall into the trap of granting this, but denying privileged, means the cluster is any more secure.

This does come up in some compilers and applications used in debugging, especially older applications. Reconsider migrating them into containers or perhaps isolate these projects to another cluster.

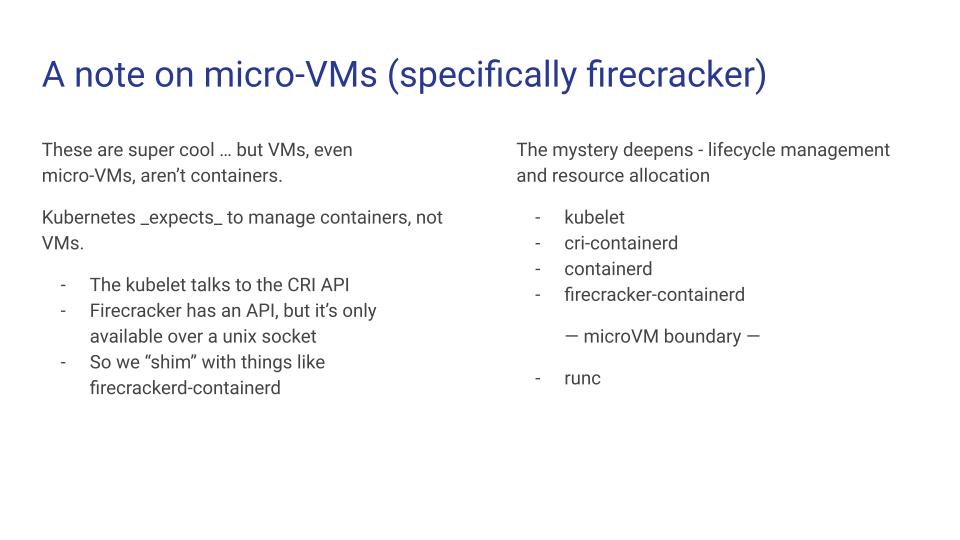

Just use Firecracker

This is usually the point in chatting about container security where someone inevitably says, “well just use Firecracker . It works for AWS!” And it does! Hooray for them! It’s a really cool tool! I want to play with it more. It could be the right solution for you, but we’re going back to the key anti-pattern here:

✨ Containers are not VMs ✨

Kubernetes expects to manage containers, not VMs. Firecracker creates (very tiny) VM with a RESTful API using kernel virtual machines . There’s a lot that doesn’t need to be specified in a PodSpec and does to define a virtual machine, and vice versa. Resource assignments and networking would be where I’d spend a ton more time if we could. This means that our pod’s lifecycle looks like this:

- The scheduler is hanging out on the control plane and gets a request to start some sort of work. The scheduler sees an appropriate node with enough resources available and asks that node’s kubelet to do the thing! The kubelet works off the PodSpec that it gets from the scheduler and thinks this is how it manages the lifecycle of that pod.

- So the kubelet talks to the container runtime on the node using the language they share, the container runtime interface , and asks it to start a new pod with whatever is in the PodSpec.

- Usually, we’re near the end of the story here, but because this is a VM and not a container, we’ve got some extra stuff to do. CRI is implemented in a plugin to the runtime

containerd, so now we’re going to bridge the next gap between what Kubernetes thinks is a container and a kernel VM that Firecracker creates. - This is where the next plugin comes into play,

firecracker-containerd(GitHub ). This adds another “translation” to what Kubernetes expects to what Firecracker can do. - Now we cross the boundary from container runtime into the firecracker microVM (and runc) and the work happens.

- Once it’s done, now we need to reclaim this VM’s resources and tell the kubelet the process is done.

See how many extra handoffs happen? Firecracker is a fabulously cool thing, but it’s not a drop-in replacement for a container runtime that Kubernetes expects. I’d recommend browsing some of the open issues and discussions in their GitHub organization (here ) to get a handle on all the ways people who were told “just use firecrackers” had problems along this path to avoid the same ones, should this still be of interest.

Next is all the things I’m aware of that I don’t know enough about to speak to knowledgeably tonight. I’m going to drop some links and maybe later follow up on them once I can play around with them some.

- Kata Containers , on GitHub

- Firekube , on GitHub

- Nestybox Sysbox, on GitHub

- It seems like there’s always another cool new thing in this category on Medium or Hacker News every month or two, so I’m sure to miss a few. 😀

Kubernetes is great. It orchestrates containers, which are not VMs. It allows an enterprise to leverage infrastructure more efficiently, allow more projects to share resources - including the most important resource, administrator/developer/engineer time. This means new skills for new tools and sometimes that isn’t in the cards.

If you want to scale VMs up and down using a cloud provider, it might be significantly easier to use their built-in VM scaling logic, especially if you can do so while maintaining VM ephemerality to get a clean and reproducible environment at every run.

Ephemerality

We’ve talked about some pretty deep architecture problems and I’ve got one more place that causes heartache - the move from a system that maintains a persistent state through a declarative service (think Ansible or Puppet ) to stateless and disposable compute units.

Last month , Brent Laster spoke in great depth about debugging pods in Kubernetes and there’s not much that I can say to build on that. Debugging pods is an art, especially when it disappears or it succeeds but didn’t return an expected value.

It is unbelievably expensive to have hundreds or thousands of developers unable to work because you got rate-limited by Docker Hub / GitHub / NPM / PyPI / whatever. While all of these tools have the ability to store local copies of artifacts/images/code/etc., local content won’t persist between runs. Make liberal use of caching and of proxy repositories. This also helps on cloud price control, as while network ingress/egress are expensive, storage and moving data around internally is cheap.

Kubernetes allows you to have read-only volumes that can be shared across many pods simultaneously. These read-only volumes can be mounted by pods for caching if read-only access is acceptable. The relevant documentation is well worth the read. Using these volumes can help reduce image size by quite a bit.

Lastly, ship your logs somewhere so you can look through them later. It’s 2022. ♥️

Sometimes, a read-only cache that can be safely shared between pods isn’t good enough. In this case, big pods are fine! (really, the latest version of conda, a Python environment and package manager, is well over 1 GB (link ))

Conclusion

I’ll never get tired of saying that ✨ containers are not VMs ✨, yet it seems like most of this evening has been all about a “lift and shift” of legacy VM infrastructure into containers without respecting that fact. And it has!

In starting this migration from VMs to containers, there’s a balance to find between a large number of discrete images that are purpose-built for each team and a small number of larger multi-purpose images. This balance is never really “complete”, but something that grows over time. The pattern I see most companies succeed with is to have a couple large-ish multi-purpose images and a process to quickly evaluate, approve/deny, and deploy project-specific images as needed. Handling requests for additional privileges or images in a timely way is critical to reducing “shadow IT” and becoming an internal service that folks enjoy. This allows admins to scale their time without compromising security.

More importantly, by providing this build infrastructure as a service and allowing some customizations, it empowers teams to exercise ownership in their build systems and the software that supplies it. Like everything else at the lots-of-people scale, it’s not an overnight elimination of the existing systems but a road to go forward together.

I want to take a moment and talk about this picture, because the gasp was audible. The cost to drain and refill this pool is easily in the 5-digit range for US dollars. My OSHA certifications are years out of date4, but as best I can see, there’s not much going on that’s terribly unsafe. You can absolutely use aerial work platforms, like the scissor lift in this picture, from a barge in water4. It looks like the two workers are tied off, are aware of pinch/crush hazards should the platform move based on how they’re positioned, and they could have personal floatation devices that inflate on contact with water, unlike a normal bulky lifejacket. I can’t see how the barge’s position is secured in the pool, but a couple tied off ropes should do the trick. Those blocks are specifically designed to float heavy things in water with an arbitrary size - so think of them as Legos for floating stuff. It was clearly stable enough to drive the lift on without toppling into the water.

But it looks so weird, right? The rules weren’t written for large swimming pools.

This is a bit of a counter-intuitive use of containers as VMs, despite my repetition of ✨ containers are not VMs ✨. Containers weren’t meant to be used this way, but it works well. The controls that an administrator has are different than for VMs or physical hardware - this doesn’t mean it can’t be done at all! Co-tenanting a bunch of different teams on a shared cluster provides enough economic advantages to incentivize some great cultural changes - empowering teams to move faster with ownership over their builds without having them also be solely responsible for it.

Resources

These are the resources linked in the slides at the end of the full deck, as well as more I’ve added in writing this out.

- Antipatterns of Cloud Applications, Microsoft Azure documentation. link

- Jérôme Petazzoni, “Do not use Docker in Docker for CI”, September 2015, link . There’s tons of info on Docker-in-Docker from @jpetazzo , but this post in particular is great for outlining why the

--privilegedwas created and why it might not be a good use for CI. - Docker’s blog on how containers are not VMs from 2016

- Containers from Scratch, a fantastic GitHub repo and YouTube showing how containers work without an abstraction like Docker

- Deep Dive into firecrackerd-containerd (DockerCon 2019), YouTube

- Ian Lewis, “The almighty pause container”, October 2017, link

- “Should I block ICMP?”, site outlining all the reasons you shouldn’t block ICMP traffic and things that break when you do.

Resources specific to GitHub Actions

- actions-runner-controller , the community project providing a Kubernetes controller for GitHub Actions.

- kubernoodles , my take on how to manage actions-runner-controller at a human scale in the enterprise.

Footnotes

-

David Kirkpatrick in “Now Every Company Is A Software Company”, Forbes magazine, November 2011, link ↩

-

All about node-pressure evictions in Kubernetes in the docs here ↩

-

Yes, I really did have an OSHA 30-hour card. While I wouldn’t feel comfortable signing off on this lift plan, it also wouldn’t have been my responsibility to do without much more training. ↩ ↩2