Explaining why a code change happened during an audit

From BSides Boulder 2024 , trying to prove why changes occurred without any additional context is difficult. Let’s work together to make that easier. This is an expanded set of slides and resources since shown live on 14 June 2024 (YouTube recording).

It’s nearly certain that at some point in the lifecycle of your audited software that you’ll need to prove something without any context or documentation about why did this happen to begin with?

Let’s talk through some hard-earned wisdom on documenting code changes over time with respect to surviving your audits. It’s difficult to understand why a change occurred without this context and impossible to go back in time to ask yourself why.

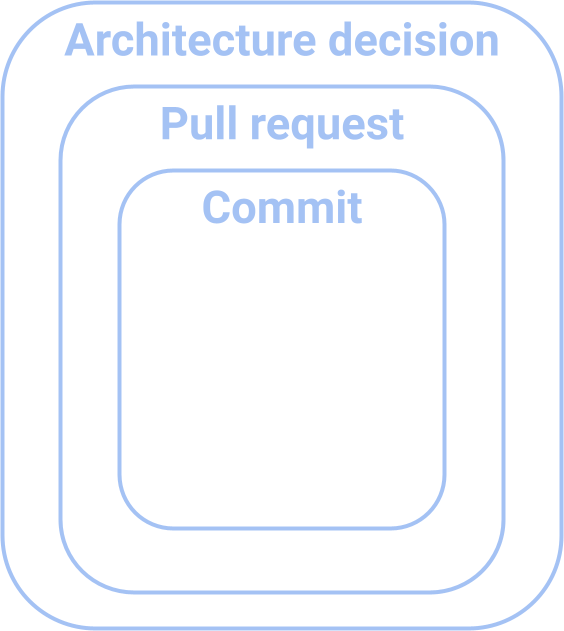

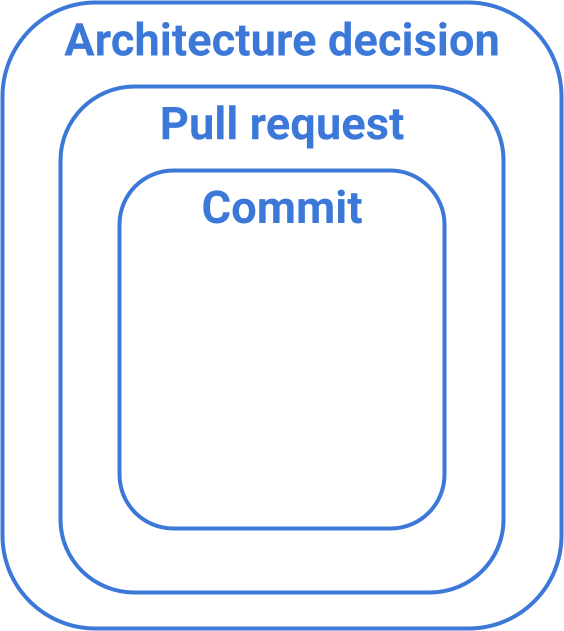

Broadly speaking, we have three places to document context around a change within a repository (mostly).

- Commit messages

- Pull requests (aka merge requests)

- Architecture decision records (ADRs)

Each of these has a broader scope or impact than the one before it. Multiple commits go into one pull request. Multiple pull requests can be covered by one architecture decision record.

We’re committed

Commits are the canonical unit of changes in git, but there’s nothing saying that it must track one-to-one with anything else with respect to an auditing framework. These are conventions out of convenience. There are about a hundred million different opinions on commit message styles and formats. To name just a few:

- Atomic commits

- Conventional commits

- European Union git commit convention

- There’s even a very handy CommitLint tool to enforce things

These conventions spur some flame wars passionate online debate. There’s good reasons to use one - it makes the history easier to scan for fix or chore or refactor commits. This is fabulous for the folks maintaining that codebase. They get to have preferences on how they work. These preferences should be respected if at all possible. I’ll not-so-humbly add to this pile of opinions.

🌻 It should never matter in an audit. Ever. 🌻

My experience is based on leading an enterprise-wide software factory. This role generally comes with a limited mandate on what it can enforce versus suggest. It’s true that what works for one team may not work as well for another. Limited time and political capital to enforce a change is more impactful spent on improving application security.

If we can’t set centralized and auditable controls as commits, what’s available to us? 🕵️♀️

Please merge my code

Here’s where it’s easiest to set most controls, provided you can explain what a pull request is. The plain language definition I’ve found that works is that a pull request says “please pull my changes into your codebase.” Sometimes it’s called a “merge request” instead, as in “please merge my code into this codebase.” It’s the same thing as far as we’re concerned.

🕵🏻♀️ This relies on that central remote to receive changes, log code reviews and tests and approvals, and use a managed identity. This makes it simple to build out workflows needed for your specific code audit requirements.

How this works in practice is a little weird once we start thinking through that transition between git and GitHub/Lab/etc.

A pull request isn’t exactly real until it’s merged. In order to track these code changes between branches (or forks, which are their own repository), git remote hosts (such as GitHub) use “synthetic”1 git references2 that are read-only. These track changes that would happen, like a future merge commit. Merged pull requests also persist, even if the branch/fork has been deleted, to provide a history of the changes that were made and the discussion that happened at the time. Because they’re read-only and not real (yet), it’s quite difficult to alter them. More importantly, they only exist inside the remote host.

Once that pull request is merged, regardless of the merge strategy in use , it becomes a real commit (or series of commits) on the receiving branch. The only context that comes over is what’s carried in those commits - messages, authors, and the like. The rest of the audit context (reviews, approvals, tests) remain in the remote host exclusively.

For most industries, the above workflow is both acceptable and preferred. This gets difficult to move code across an air-gapped environment between remote hosts. That extra data in a pull request may not be able to be migrated with the code using the API of your chosen platform. In these cases, consider using as much of the API as possible to create plain text or machine-parsable artifacts (such as test outputs or scan results) to store for future audits.

Record this big decision

To preserve portability and history within the codebase, big changes should write an architecture decision records instead of pull requests or external systems (such as a ticket tracker). The format of these can vary by team, but the common things included are:

- Title: A short description of the decision

- Status: Accepted, Rejected, Deprecated, Superseded, etc.

- Context: Why is this a problem? Why should we address it?

- Considered: What are the options?

- Decision: What are we going to do about it?

- Limitations: What are we not going to do?

- Consequences: What happens if we do this?

These are collaborative documents. If there are three opinions on what to do, writing all three down and committing to the decision is important. A few years from now, the entire team will likely be different and those left will definitely not remember everything about it. Contemporaneously writing things down with your code, your corporate identities, and difficult-to-manipulate dates means that it’s that much less work to do when turning over evidence on why a change was made.3

Opinion

Despite a ton of opinions on these, many things simply do not matter in an audit - a team’s commit syntax, merge strategies, or template for writing choices down. Just like in every other facet of life in regulated industries, contemporaneous documentation of the decisions made and the context around them remains critical to proving changes. Being too controlling or lacking the flexibility for preferences drives shadow IT - making a difficult audit impossible.

I’ve found using pull requests for change control and ADRs for documentation to be the best balance between control and flexibility that I needed as the responsible party for source control, yet allows for most teams the freedom to work as they please. 🗽

Writing it down when it happens remains the best way to prove why something happened in the future.

🕵️♀️ Next up - BUT WHY THOUGH?! Why should we work in regulated industries when developing software is hard enough to begin with - without audits making life so much harder? Part 8: Why develop when you have to audit

Footnotes

-

Same general feature with a different name for other repo hosting products. “Pull request” and

refs/pullin GitHub becomes “merge request” andrefs/merge-requestin GitLab or “pull request” andrefs/pull-requestin Atlassian products (BitBucket/Stash). Atlassian has a great blog article about why these refs exist here . ↩ -

You can read more about git references in the documentation . ↩

-

The 18F ADR summary is a great little document from a fantastic organization that shows how to get started writing ADRs. ↩